- Healthcare Services

- Find a Doctor

- Patient Portal

- Research and Education

Your recent searches

- Find a Location

- Nursing Careers

- Physical Therapy Careers

- Medical Education

- Research & Innovation

- Pay My Bill

- Billing & Insurance Questions

- For Healthcare Professionals

- News & Publications

- Classes & Events

- Philanthropy

How to Deal with Re-entry Anxiety and Post-pandemic Stress.

By Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, Chair, Psychiatry

- Medstar Facebook opens a new window

- Medstar Twitter opens a new window

- Medstar Linkedin opens a new window

Find care now

If you are experiencing a medical emergency , please call 911 or seek care at an emergency room.

After more than a year of COVID-19 social restrictions, the U.S. pivoted from “you’re safer at home” to “get vaccinated and get back in action!” within a matter of weeks.

For some, the change was a major relief. But for many, the quick transition added fuel to a growing inferno of pandemic-related anxiety. Will I get sick if I return to the office? Is the vaccine safe? What if someone confronts me for wearing a mask?

Whether you are an introvert, extrovert, or somewhere in the middle, feeling a little rational anxiety —fact-based concerns—about “returning to normal” is expected and reasonable. However, excessive rational or irrational anxiety —unfounded worry—can prevent people from smoothly resuming social and career encounters that benchmark a healthy, happy life.

When I see patients for behavioral health care , I ask how the pandemic has affected them. Answers vary based on personal factors, such as whether they:

- Caught the virus or witnessed a loved one get sick

- Are suffering from long-term COVID-19 side effects, such as depression, memory loss, or “brain fog”

- Worked from home or in person with the public

- Lost their job

- Had their children at home 24/7

- Homeschooled their kids

- Took care of aging parents

- Were safe at home during lockdown

Even people who weren’t overtly affected personally by COVID-19 may be “languishing”—struggling to feel “normal” again after months of societal turmoil. The truth is, life is unlikely to revert to the “normal” we were used to, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing.

Despite the tragedies of the pandemic, some positive changes will hopefully continue, such as more choices for remote employment; increased telehealth options; and the precedence for staying home from work when we’re ill.

Still, rational and irrational anxiety is causing roadblocks for many people who want and need to move on from the pandemic. The good news is that re-entry anxiety is manageable when you are ready to start healing. Let’s discuss the differences between rational and irrational anxiety and what support services are available.

Post-pandemic #anxiety is a real and common problem. But help is available to manage the rational and irrational stressors of re-entering society. Elspeth C. Ritchie, MD, MPH, discusses tips to reclaim your quality of life: https://bit.ly/2UlFyQ9.

Click to Tweet

Rational vs. irrational anxiety.

Rational anxiety is rooted in truth. For example, at the time of this writing, the U.S. is widely lifting domestic travel restrictions. Simultaneously, new virus variants are emerging and we’re hearing news of catastrophic viral spread in Brazil and India. It’s natural to worry whether our country is on the right track.

Other rational pandemic-related fears may include:

- Going in public after having COVID-19: If you or a loved one were affected by the virus, it’s rational that you might be more concerned about spreading the virus or catching it again.

- Traveling by mass transit: Close proximity with others in an enclosed space can be a recipe for illness—a fact-based concern, regardless of the pandemic.

Irrational anxiety is characterized by unsubstantiated worry or fear when there is clear evidence to the contrary. In daily life, this may include hesitance to enter a tall building or feeling terrified by an innocuous sight or sound.

Irrational pandemic-related anxiety may include conspiracy theories, such as:

- Obsessive worry that Americans are being microchipped through the vaccine: More than 80% of U.S. adults use smartphones , which already enable geolocation. The idea of going to such great lengths for tracking is as unreasonable as it is unlikely.

- Fear of developing COVID-19 from the vaccine: This is scientifically impossible, since there is no actual virus, alive or dead, in any of the approved vaccines.

Both rational and irrational anxiety can absorb one’s thoughts, making it tough to focus, perform daily tasks, or even leave home. However, both can be treated with a thoughtful approach to how we perceive and react to pandemic-related stressors.

Related reading: How to spot depression and anxiety in teens.

8 anxiety management strategies.

Some patients with newly diagnosed or existing-but-worsened anxiety may benefit from medication. However, symptoms often can improve significantly with supportive, guided behavioral changes to help you regain control of anxious feelings.

1. Control the controllables.

A proven technique for managing anxiety is to focus on what you can control and minimizing what you can’t. Throughout the pandemic, many patients had trouble sleeping due to racing thoughts, such as an overwhelming fear that we were all going to die. I’ll admit, this worry crossed my mind at the beginning of the pandemic.

Yes, all of us will die someday. That is not something we can control. But what we can control is how we handle the present. I typically recommend that patients work through an internal dialogue about what they can and can’t control. This can help you find positives on which to focus your thoughts.

For me, my “controllable” was getting up, getting ready for work, and presenting my best self for my patients. What might “controllables” look like in your situation?

2. Practice deep breathing.

Take deep breaths through your nose and exhale out of your mouth. Repeat this 10 times. Focusing on manual breathing subconsciously refocuses your mind away from whatever was bothering you, if even for a moment. Deep breathing is a form of mindfulness, which is key to more sophisticated awareness practices, such as meditation.

3. Set healthy boundaries.

Several friends invited me to dinner a few weeks back. We’d all been vaccinated, but I requested that we all sit outside where it’s well-ventilated. I still preferred to wear my mask, and I decided in advance that I would leave early to avoid excessive hugging, handshakes, and crowds. What I told all my friends was that I had to be home at a certain time, and no one gave me a hard time about leaving before they did.

It’s up to you what you are comfortable with. Conversely, we owe it to each other to be kind if someone isn’t as ready as you to unmask or hang out at an event or in a restaurant.

Related reading: 6 signs you should be concerned about your mental health.

4. Exercise outdoors.

Moving and getting a change of scenery can help reset the mind and body. I enjoy walking around the koi ponds and flowers at MedStar Washington Hospital Center when I have a few moments between appointments.

If you live in Southern Maryland, you may have easy access to enjoy outdoor activities such as fishing, crabbing, canoeing, and boating. In Baltimore, you might catch a baseball game. Find an activity you enjoy and take your mind off worrying for a while.

5. Give back.

It can be tough to make yourself participate when you have anxiety. However, volunteering can temporarily replace racing thoughts by helping you focus on something positive. Animal lover? Volunteer at a pet shelter. Enjoy reading? Offer to read to kids at your local library. Worried about the homeless? Help out at a food bank. There’s always work to be done, and plenty of opportunities to help in your passion area.

6. Laugh a little!

At the start of the pandemic, I began carrying a stuffed lemur in the pocket of my hospital coat. Patients and colleagues would walk by, give me an odd look, then burst out laughing. Every time, I would beam ear-to-ear behind my mask. Laughing feels good, and it feels even better to make others laugh!

7. Prepare for naysayers.

There will always be a few people who feel it is their right to ridicule others for wearing or not wearing a mask as restrictions are lifted. At work, ideally you could turn to your boss or human resources professional to proactively manage or mitigate these situations. However, that’s not always possible.

If you feel comfortable speaking your mind, remain polite but firmly state, “I respect your decision. Please respect mine.” Sometimes it helps to plan out what you will say or do in certain situations. Role playing with your therapist or a friend can help build your confidence.

8. Take your time.

Whether you are anxious about returning to work or taking your first post-pandemic vacation, incremental steps are key. In our practice, we often recommend “extinction” or “exposure therapy,” which incorporates visualization to manage stressors.

For example, if a patient is afraid of crossing bridges, they’ll start with visualizing themselves crossing the bridge. Once they’ve mastered that, we arrange for them to cross a bridge with a loved one. Over time, they can work up to crossing solo. Some patients never cross alone, and that may be sufficient for them. The point is to set realistic, personally achievable goals you can stick to and go from there.

As we all adjust to our post-pandemic society, remember: Everyone’s timeline will be a little different based on their mental health and their experiences over the past tumultuous year. If anxiety is interfering with your life, don’t hesitate to seek help. We’ve been here for you, and we will be here—no matter what curveballs the next year throws our way.

Struggling with post-pandemic anxiety? The mental health team at MedStar Health is here to help. click below.

Request an Appointment

Stay up to date and subscribe to our blog

Browse by category.

- Behavioral Health

- Dermatology

- Gastroenterology

- Healthy Eating

- Heart and Vascular

- Living Well

- Neurology and Neurosurgery

- Orthopedics

- Physical Therapy

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Primary Care

- Sports Medicine

- Womens Health

Latest blogs

Post-COVID Travel Anxiety

How to cope.

Dr Sarah Jarvis is the Clinical Director of the Patient Platform, an active medical writer, broadcaster, and the resident doctor for BBC Radio 2.

I think it's fair to say that for pretty much everyone, it has been a very strange couple of years. As the new decade dawned in January 2020, there were vague murmurings of a new infectious disease affecting parts of China. Within 3 months, the UK was locked down due to COVID-19 and travel had effectively ceased, at least where leisure was concerned. Even business travel pretty much halted – in the second quarter of 2020, UK air travel dropped by 97%.

While foreign travel remained off the cards, summer 2020 saw the rise of the staycation – promptly followed by a rise in COVID-19 cases and a second lockdown. The small number of people who did venture overseas lived with a constant risk of having to change their plans at short notice as new restrictions were introduced in response to rising cases.

Even in 2021, air travel in and out of the UK had slumped by 71% compared to pre-pandemic levels. For those who did decide to holiday abroad, there were seemingly endless changes to COVID-19 testing requirements and huge variations in regulations between countries.

So as the world opens up in 2022, it's hardly surprising that so many of us feel anxious. The newspaper headlines of the last 2 years mean that most of us have heard about the travel woes experienced by holidaymakers, even if we weren't among them. In addition, after 2 or even 3 years of not making regular holiday trips, we're no longer as familiar with the routine of packing essentials, checking flights, and coordinating travel plans with loved ones.

Be prepared

One of the key causes of anxiety is feeling out of control. And one of the best ways to avoid being out of control is to be prepared. That will allow you to breathe easy and enjoy your trip, confident that there won't be any nasty surprises in terms of COVID-19 regulations.

While COVID-19-related regulations for people in, and entering, the UK have gone, taking time to find out about regulations in the country you're visiting is an important first step.

There is no longer any need to take any COVID-19 tests or fill in a passenger locator form if you're travelling into the UK. This applies to Brits returning from holiday, as well as to people from other countries visiting the UK. There is also no difference in testing requirements depending on whether you've been vaccinated against COVID-19. That undoubtedly reduces complications, as you won't need to find a registered test centre while you're away or book a test to take shortly after you get home.

However, it is still very important to check the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) travel advice well before you go. In particular, their country-specific pages provide the latest COVID-19 travel advice for the country you're visiting. The number of countries with pandemic-related travel restrictions is shrinking all the time, but by checking in advance you can know you won't be caught out.

It's worth remembering that if you have a connecting flight, you'll need to find out if there are any different recommendations and requirements for any transit countries.

In the UK, there is no longer any legal requirement to self-isolate or report your results if you test positive for COVID-19. Nonetheless, self-isolating if you catch COVID-19 is still strongly advised, because of the risk the infection still carries (particularly to clinically vulnerable people and those who aren't vaccinated).

Of course, free Lateral Flow Tests are no longer available in the UK. But they are now available to buy for as little as a couple of pounds in the UK. In other countries, it may be harder to track down a Lateral Flow or PCR test.

So you may want to consider buying a couple of tests to take with you. This will mean that if you do develop symptoms that might be due to COVID-19, you can test yourself – and often be reassured that your test is negative, so you don't need to worry. It's worth thinking in advance about what you should do if you do test positive. For instance, does the hotel you're staying at have rules, and can they provide support for you to self-isolate?

Step by step

One of the great joys of holidaying abroad is the chance to sample new foods, whether it's local delicacies or popular 'imported' dishes such as pizza or curries, made in the way they were first designed. Usually, this is a treat - but if you haven't eaten out much in the last couple of years, the prospect of braving a crowded restaurant several times a day can be daunting.

A few simple steps will help make you feel more confident:

- Practice eating out. 'Exposure therapy' is commonly used by healthcare professionals treating people with anxiety. Eating out a few times in venues you're familiar with, close to home, will help you ease yourself into some aspects of eating with strangers.

- Quiet times. Find out from your hotel or restaurants you're considering when they are at their busiest. For instance, in many parts of Europe, it's common for people not to go out to dinner until late in the evening. In the USA, by contrast, restaurants may be packed at 6pm and have quietened down by 8.30pm. Plan your mealtimes to avoid the busiest periods.

- Go al fresco. We learnt within months of the pandemic starting that the risk of catching COVID-19 is much smaller outdoors than inside. Make the most of the balmy weather and the tradition of dining al fresco to eat outside. You may need to approach your hotel or restaurant in advance and explain your concerns – they will often be happy to oblige by reserving a table outside.

- To mask or not to mask? Wearing face coverings is no longer mandatory in the UK (except in some healthcare settings). Wearing a standard cloth face-covering doesn't offer you, the wearer, much protection. However, it does protect those around you. In many foreign countries, it's still standard for people to wear face coverings indoors. If this would make you feel safer, check with hotels and restaurants what their policy is.

Peace of mind

While the likelihood of becoming seriously unwell if you catch COVID-19 is much lower if you've been vaccinated, it is still important to make sure any medical problems are covered by your insurance. If you have medical conditions which you haven't declared – or don't have specialist travel insurance that covers you for those conditions – you could find your insurance is invalid if you need urgent medical help.

So for peace of mind, it's essential to know that you have insurance that will allow you to access care in any eventuality. And if you have any medical conditions, the best way to do that is to get insurance from a provider who specialises in providing cover for people with conditions such as yours.

The bigger picture

Of course, travel anxiety has been around since long before the pandemic. It's more common in people who have other mental health conditions, such as anxiety disorders or depression . However, there are also many people who cope perfectly with stress-inducing situations in the rest of their lives, but who struggle with travel anxiety.

- Share this page on Facebook

- Share this page on Twitter

Sign up to receive regular updates

Get the latest news, advice, travel tips and destination inspiration straight to your inbox.

- skip to Cookie Notice

- skip to Main Navigation

- skip to Main Content

- skip to Footer

- Find a Doctor

- Find a Location

- Appointments & Referrals

- Patient Gateway

- Español

- Leadership Team

- Quality & Safety

- Equity & Inclusion

- Community Health

- Education & Training

- Centers & Departments

- Browse Treatments

- Browse Conditions A-Z

- View All Centers & Departments

- Clinical Trials

- Cancer Clinical Trials

- Cancer Center

- Digestive Healthcare Center

- Heart Center

- Mass General for Children

- Neuroscience

- Orthopaedic Surgery

- Information for Visitors

- Maps & Directions

- Parking & Shuttles

- Services & Amenities

- Accessibility

- Visiting Boston

- International Patients

- Medical Records

- Billing, Insurance & Financial Assistance

- Privacy & Security

- Patient Experience

- Explore Our Laboratories

- Industry Collaborations

- Research & Innovation News

- About the Research Institute

- Innovation Programs

- Education & Community Outreach

- Support Our Research

- Find a Researcher

- News & Events

- Ways to Give

- Patient Rights & Advocacy

- Website Terms of Use

- Apollo (Intranet)

Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Like us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- See us on LinkedIn

- Print this page

News May | 7 | 2021

Post-Pandemic Anxiety: Feeling Stressed as Things Return to Normal

As COVID-19 vaccinations roll out across the U.S. and states begin lifting various restrictions, many have begun thinking and dreaming of life post-COVID. And while the thought of gathering with family and friends again, traveling and getting back to loved activities can feel joyful, many are surprised to also feel stressed and anxious about the “return to normal.”

Soo Jeong Youn, PhD, a clinical psychologist in the Department of Psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital and an assistant professor in psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, discusses a few scenarios that can be a source of stress, and what people can do to help make the transition back into post-COVID life a bit easier.

COVID-19: Stressful or Traumatic?

While the pandemic has been a global event that has had an unimaginable impact on everyone’s life, not everyone has had the same pandemic experience. In some cases, the pandemic has been a source of trauma.

“A traumatic event is defined as actual or threatened death or serious injury by the DSM-5 ( Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5 th edition),” says Dr. Youn. “Depending on what your role is, what your job is, and how the pandemic has impacted you and your loved ones, you may have been exposed to a traumatic event.”

“But the important thing is that, regardless, everyone has been exposed to incredible stressors over the past year. We know that we're going to be dealing with long-term mental health consequences . The acute phase may be over, but we're going to be working through the chronic consequences for a while. Experiencing mixed reactions as we transition back is to be expected.”

Dealing with the Emotional Ebbs and Flows of COVID

These mixed reactions can be both situational and cyclical.

“Some people may have occasional worries that are contained to certain aspects of their life, or may be time limited” Dr. Youn says. “The beginning stage of constructing a 'new normal' is a period of transition. As we're building that new normal, there might be some worries and anxiety, but they dissipate as we get used to it all.”

For example, says Dr. Youn, being in larger groups of people or returning to the office after more than a year of isolating can be hard, especially if vaccination status is unknown, but may get easier over time. In other instances, transitioning back may feel fine, but then you may experience stress later. This is especially true for parents who may enjoy a less restrictive summer with their kids, but begin to feel anxious about their child’s personal safety, whether they’ve fallen behind academically or if their social connections with their friends have suffered as they head back to school.

It is important that as people go through this transition, they pay attention to how they are feeling and get help if needed says Dr. Youn.

“If a person notices that after a month or so there is no change whatsoever in how they are feeling, and they are experiencing very heightened levels of anxiety that is impacting their day-to-day functioning, their mood or their family, then they may want to consider talking to a mental health professional, especially if it is affecting multiple areas in their life.”

Gathering Again: How to Do So Safely

- Start slow: If you know that in a month’s time you’ll begin socializing with larger groups of people, meet with one person now and slowly grow your circle. Follow all COVID safety protocols like distancing and wearing masks, but begin interacting with people at a pace that is right for you to help lessen anxiety

- Know and maintain boundaries: Friends and family may have different comfort levels with different activities than you may have. In these cases, it is important to know your boundaries and clearly communicate them. These boundaries may shift depending on the situation and relationship, but the hope is that you are with people who will understand and come to an agreement on safety

COVID-19: A Gift of Time

For some, COVID-19 was a gift of time where they thrived. A slow-paced, flexible lifestyle may have helped them focus on themselves or family or work on individual goals that they didn’t have time for beforehand.

Dr. Youn offers advice on how to continue thriving when the pace picks up again: “Understanding first what were the components that were really helpful in succeeding under the circumstances is going to be important so that we can then figure out how to maximize those factors in the day-to-day. Now the trick is to figure out how to recreate those structures during the transition and build them into a normal life.”

A source of stress for others is the feeling that they did not use the COVID downtime in a productive way. While this may feel like a failure for some, Dr. Youn is clear: surviving the last year is a triumph.

“We cannot minimize the emotional and physical toll that the pandemic had on us,” she says. “It is going to be immeasurable for a long time. So whatever we did to truly survive the last year cannot and should not be dismissed. We have done everything that we can and we're here and wanting to rebuild a new future, whatever that may look like. That is a huge triumph.”

Related Links

- Tips To Improve Mental Health With Nutrition

- COVID-19 Vaccine Approval and Distribution FAQ

Centers and Departments

- COVID-19 (Coronavirus)

- Mental Health

Related News and Articles

- Press Release

- May | 23 | 2024

Century-old Vaccine Protects Type 1 Diabetics from Infectious Diseases

BCG-treated individuals had a significantly lower rate of COVID-19 infection compared with the placebo group and a significantly lower rate of infectious diseases overall.

- Apr | 15 | 2024

Research Spotlight: How Often Were Adults With Down Syndrome Listed as Do-Not-Resuscitate During the COVID-19 Era?

Researchers found that a person with a diagnosis of Down syndrome and COVID-19 pneumonia had six times the odds of having a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) status ordered at hospital admission.

- Oct | 23 | 2023

Research Spotlight: Learning More About the Distribution and Persistence of mRNA Vaccines in the Body

Aram J. Krauson, PhD, of the Department of Pathology at Mass General, is the first author and James Stone, MD, PhD, is the senior author of a new study in NPJ Vaccines, Duration of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Persistence and Factors Associated with Cardiac Involvement in Recently Vaccinated Patients.

- Oct | 5 | 2023

Clinical Trial Reveals Benefits of Inhaled Nitric Oxide for Patients with Respiratory Failure Due to COVID-19 Pneumonia

Treatment improved blood oxygen levels and lowered the risk of long-term sensory and motor neurologic symptoms.

- Sep | 27 | 2023

Study Reveals More Depression in Communities Where People Rarely Left Home During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Results indicate a link between reduced mobility during the pandemic and greater risk for depressive symptoms.

- Aug | 10 | 2023

Transplant Recipients Experience Limited Protection With Primary COVID-19 Vaccination Series, but Third Dose Boosts Response

For lung and heart transplant recipients, vaccine doses beyond the third dose are likely important for maintaining immunity.

Post-COVID Anxiety Is Real

Here are 5 proven ways to beat it, and to benefit from post-traumatic growth..

Posted September 30, 2022 | Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

- What Is Anxiety?

- Find a therapist to overcome anxiety

- It's normal to experience anxiety trauma after a life-altering dangerous event.

- The key is to retrain your nervous system to strengthen the parasympathetic tone, or the calming response, as opposed to fight-or-flight.

Have you noticed that you have been more hypervigilant since the pandemic? And perhaps a bit more anxious in public? After a life-altering and life-threatening event, this is normal. Any shocking situation that involves life and death can lead to trauma.

Here's why people developed it during the pandemic: In many ways, Covid-19 trained us to become hypervigilant to contact with other people or potential contamination.

Clinically speaking, hypervigilance is a trait of anxiety . So, in many ways, the pandemic may have taught some of us to be hypervigilant to stay safe. In military contexts, service members are trained to be hypervigilant for safety, to seek out signs of danger, and to avoid potential threats. When they leave the military, they often find that even if they don’t have trauma symptoms, their hypervigilance remains because it was part of their training. For example, many veterans who have long left the military still locate exits whenever they enter a building or always keenly observe their environments for signs of danger. We might, then, expect those who endured the stress of the pandemic to remain anxious and hypervigilant for quite some time.

What can we do about this? The key is to retrain your nervous system to have a greater parasympathetic tone: the calming response, as opposed to fight-or-flight. When you do so, you might see that, from any traumatic experience, there can be post-traumatic growth .

Breathing exercises are a quick, efficient, and effective way to calm down anxiety by triggering the parasympathetic (“rest and digest”) nervous system. We come out of our sympathetic (“fight-or-flight”) response and return to a calmer state, our perspective broadens, and we can see things from a more rational perspective.

When you inhale, your heart rate increases. When you exhale, it slows down. Taking just a few minutes to close your eyes and lengthen your exhales (making them twice as long as your inhales) will help you calm down in minutes.

Our research has shown that one breathing technique, SKY Breath Meditation , can improve anxiety and depression while increasing well-being to a greater extent than other well-being practices, such as mindfulness . In addition. it may be a good complement or adjunct practice to traditional treatments for trauma.

Meditation: A regular meditation practice has been shown to improve stress, anxiety, and depression, boosting emotion regulation , well-being, and even physical health. The psychological benefits associated with meditation make it well worth trying out. Gentle Yoga, Tai Chi, Yoga Nidra—any physical movement or relaxation that settles the mind and induces a meditative state activates the parasympathetic nervous system. Regular practice trains your body to calm down faster and be calmer at baseline.

Nature: Exposure to nature has also been shown to profoundly benefit mental health , boosting well-being while lowering stress and anxiety. Even a limited amount of exposure can have a major impact. If you can't go out on a hike, having a poster of a nature scene on your wall can make a difference, as can a nature screen saver or a plant on your desk. That's how profoundly exposure to the natural world can impact us.

Compassion: Many studies have shown that being of service, in any capacity, improves your mental and physical health while contributing to longevity. Whether you are visiting a lonely aunt or volunteering at your local pet shelter, when you help others, it helps you . The impact of small acts of kindness or community service can be tremendous, even helping with recovery from disease.

Self-Compassion: So many of us are self-critical and hard on ourselves. In the process, we harm our mental and physical health, increasing our anxiety. Self-compassion involves treating yourself as you would treat a colleague or friend who may not have lived up to expectations in a given situation. Rather than berating, judging, and thereby adding to your friend’s despair, you would listen with understanding and encourage your friend to remember that mistakes are normal, without fueling the fire. Better mental and physical health, improved relationships, and a greater parasympathetic tone show the result of self-compassion.

To find a therapist near you, visit the Psychology Today Therapy Directory .

Emma Seppälä, Ph.D. , is a Lecturer at the Yale School of Management and is the author of SOVEREIGN: Reclaim your Freedom, Energy & Power in a Time of Distraction, Uncertainty & Chaos.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Dealing with travel anxiety in a post-COVID world

Travel has many benefits for our wellbeing but can be an overwhelming prospect post-covid. here’s how to manage travel anxiety, so you can get back out there..

Tags: Health COVID19 Achieving in life Real Wellbeing factors

“Travel is a coping mechanism that a lot of people have been without for quite a few years, which is contributing to that burnt-out feeling. It’s a reset time for your brain, and people who travel regularly do see the benefits in their mental health.”—Georgia Maling, Mental Health Coach, MindStep.

- Travel has significant benefits for our wellbeing, giving us something to look forward to and a fresh perspective on life.

- If you’re feeling anxious or stressed about travel, realise this is normal and aim to control the things you can control.

- Following COVID-safe guidelines is a proactive way to alleviate some of the stress of travelling.

The gently crashing waves. The hustle and bustle of an exotic city. The treks through rice paddies, over mountains and past ancient ruins.

However you choose to do it and wherever you go, travel is an act of self-care—a chance to unwind, reset and re-centre. At least, it was before the pandemic snapped borders shut, keeping us stuck in our suburbs, states and country.

Now that travel is back on the cards, it seems many of us are reluctant to take the plunge. So what’s standing in our way? And why is it worth facing our fears to get back out there?

Where did all our wanderlust go?

After being unable to travel abroad for more than two years, you’d expect people to be very eager to get out and about. But it seems almost the opposite is true, with international tourism down to a mere trickle.

It makes sense when you think about it, though. After all, many of us have already suffered repeated disappointments caused by the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021, while others may be anxious about the chance of contracting COVID or getting stuck overseas.

“Unfortunately, I think COVID over the past couple of years has made us quite hypervigilant to things that aren’t certain,” says Georgia Maling, a coach for mental health program MindStep, delivered by Australian Unity’s health division Remedy Healthcare. “So many people have had plans disrupted, particularly if you were living in Victoria, with the various sudden lockdowns that we’ve had and the cancelling of plans over and over and over again.

“I think people are quite cautious about that and the disappointment that comes along with it, so they’re trying not to expose themselves to the potential for that happening again.”

But, she adds, if you never expose yourself to the risks associated with travel, you’ll never get to experience the benefits and rewards that come along with it.

The Real Wellbeing benefits of travel

There’s nothing wrong with a bit of routine, but after a while the endless cycle of “eat, work, sleep, repeat” can be very draining, leading to feelings of numbness, fatigue and even burnout.

A change of scenery can help shake off stale energy, and planning the trip can give you something to look forward to, Georgia says. In her opinion, “researching accommodation, fantasising about what you’re going to do, eat and see—that’s half the fun!”

The time away can do wonders for your Real Wellbeing too, with travel being shown to reduce stress, improve brain function, increase creativity and boost mental health.

“Travel is a coping mechanism that a lot of people have been without for quite a few years, which is contributing to that burnt-out feeling,” Georgia says. “It’s a reset time for your brain, and people who travel regularly do see the benefits in their mental health.”

Come home reinvigorated, with a fresh perspective

Another benefit of travel is that it broadens your world view, giving your perspective a much-needed shake-up.

“It is known that your empathy increases when you see and experience different cultures and different ways of living,” Georgia says. “Seeing that diversity, making international friends, studying languages, different types of food and music—this all helps build your world view and your world perspective.”

You’ll come back refreshed and energised and will likely see your life in a whole new light, because “travel also gives you a greater appreciation for your own surroundings”.

How to manage travel-related stress in the COVID era

It’s perfectly normal to feel nervous about travel post-COVID—whether it’s thinking you might get sick, or just because it’s been a long time since you’ve done it.

But focusing disproportionately on things we can’t control causes anxiety and actually isn’t going to do you any favours.

“Anxiety and stress come from predictions about what may or may not happen in the future—and if your brain is working so hard to prepare for everything that may happen, that just sounds exhausting,” Georgia says. “It also means your travel is not going to be as pleasant an experience as it could be, and all those benefits will be overshadowed by the stress.”

Her advice is to instead focus on what you can do to troubleshoot some of your top concerns. For example:

- If you’re worried about getting stuck overseas, have a chat with your workplace about your capabilities to work remotely or the potential for flexibility to extend your plans if that does happen.

- Make sure you have enough funds to cover extended accommodation and other daily costs.

- Read over the terms of your travel insurance so you know what you’re covered for.

Following COVID-safe guidelines is another proactive way to focus your energy and attention, according to Steve Hollow, Head of General Insurance at Australian Unity .

“In terms of domestic travel, simply follow the COVID-safe advice—get vaccinated and boosted, wear masks when travelling in crowded spaces, such as public transport and planes,” he says.

Meanwhile, for international travellers, Steve has these top tips:

- Make sure you have travel insurance that protects you if you contract COVID before you travel or while you’re travelling.

- Check the government’s Smart Traveller website to understand the requirements of the destinations you want to travel to and follow the advice on the site.

- Take all the precautions you can to avoid contracting COVID in the first place.

There’s such a thing as being overprepared

While it always helps to be prepared, Georgia points out that it is possible to overdo it.

“Some clients tell me that they’ll double- and triple-check that they have everything in their suitcase before flying,” she says. “I think we’d all agree that one to two checks are sensible and reasonable, but once you get up to that third and fourth check it’s probably just adding to your stress and making you doubt yourself more.”

Besides, no matter how hard you try, there’s no getting around the fact that, from time to time, even the best laid plans can and do go awry. But, Georgia really believes that the upsides of travel outweigh the potential risks.

“Overall, just do it,” she says. “Taking some time away from work, seeing new places, it does release the stress that you’ve been holding onto—and releasing that stress and tension relaxes your mind and helps you to heal.”

Disclaimer: Information provided in this article is not medical advice and you should consult with your healthcare practitioner. Australian Unity accepts no responsibility for the accuracy of any of the opinions, advice, representations or information contained in this publication. Readers should rely on their own advice and enquiries in making decisions affecting their own health, wellbeing or interest. Interviewee titles and employer are cited as at the time of interview and may have changed since publication.

Remedy Healthcare Group Pty Limited and Australian Unity Health Limited are wholly owned subsidiaries of Australian Unity Limited.

An Australian Unity health partner, Remedy Healthcare provides targeted, solution-oriented healthcare that is based on clinically proven techniques. For more than 10 years, Remedy Healthcare has worked with more than 100,000 Australians – helping them to manage their health through caring, coaching, empowerment and support.

Related Articles

Need to know: all about chiropractic

From back and neck pain to headaches and more, chiropractors treat our body’s “mechanical” problems. Here’s your need-to-know guide to chiropractic.

What is osteopathy?

An osteopath takes a whole-body approach to help you treat or prevent injuries, aches and pains. Here’s what you can expect from osteopathy.

Taking a close look at endoscopy and gut health

A gastrointestinal endoscopy, or endoscopy for short, is a common medical procedure undertaken by many Australian Unity Members. But what is it, when is it used, and how is it used to improve gut health?

Supporting your wellbeing

Health services, wellbeing experts.

clock This article was published more than 3 years ago

How long will it take to overcome our pandemic travel anxiety?

Thomas Plante is grounded — by choice.

“The pandemic made me realize that I really would prefer not to travel at all,” says Plante, a psychology professor at Santa Clara University in Santa Clara, Calif.

Why stay home? Travel, with all its testing, quarantining and mask requirements, is a hassle. It’s also risky. People like Plante are turning inward, which is not only simple but safe.

“The pandemic has allowed reflection and discernment about a lot of things,” he says. “Travel is just one of them.”

Others apparently feel the same way. While the travel industry is abuzz with talk of pent-up demand and a historic resurgence, some erstwhile travelers are opting to stay home, possibly for good.

Miami psychiatrist Arthur Bregman says he has seen an uptick in patients who are reluctant to leave home as a result of the pandemic. He has coined a term for this feeling: “cave syndrome.”

“It’s about loving isolation to the point that you become dysfunctional,” Bregman says. “While this phenomenon is not directly connected to covid-19, it’s been exacerbated by the anxiety of uncertainty and its effects on our lives over the past year.”

For some, the disinclination is temporary. Travelers such as Alix Strickland Frénoy, an American who lives in Paris, are taking virtual trips. Her latest excursion, via laptop, took her to a number of castles, from the Château de Pierrefonds in the Oise, in northern France, to Miramare Castle in Italy.

“My husband and I love traveling virtually during the lockdown,” says Frénoy, who runs an educational website . “We haven’t done any actual physical travel in more than a year.”

For some travelers, the change feels permanent. Since the pandemic started, I have spoken with many readers who say they don’t see how they can go anywhere again and feel safe.

They’re people like Roslyn Hopin. Before the pandemic, she made plans to fly to Kazakhstan in fall 2020. But, at 89, Hopin felt that the risks of travel were too great and asked for a refund from Turkish Airlines. The airline returned her money in less than a week.

Hopin, a retired saleswoman from Delray Beach, Fla., does not expect to try again this year. “I had hoped to have this adventure in 2021,” she says. “But it does not look like it will happen.”

Definitely not. The U.S. Embassy in Kazakhstan has warned potential travelers to reconsider planned visits to that country because of the coronavirus , noting that its borders remain closed to foreigners, with limited exceptions.

Hopin says that she wants to travel again but that she’s concerned that it may not be safe to go anywhere for a while. Staying home is the only safe choice for her, at least for now.

I may have a touch of cave syndrome, too. I spent six months locked down in Sedona, Ariz., during the last surge. And I quietly congratulated myself for keeping my three kids safe while the virus raged outside. I firmly said no to weekend trips to California and day trips to the Grand Canyon. But by the fourth week, the travel writer in me was screaming, “Let me out!”

We finally pulled up stakes this month, embarking on a long road trip to the East Coast, but only after I had received both my shots. Part of me wanted to stay in Sedona until the pandemic ended.

Bregman says that after the 1918-1919 flu pandemic, some Americans suffered from what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder. Although he has not seen anything as severe as PTSD in the general population’s reaction to this pandemic, there is a considerable amount of anxiety among his patients. In fact, it remains high even as the public health outlook improves. It’s manifested in your vaccinated friends who still won’t go out, he says. “They’ve fallen in love with their cave.”

So, do you have cave syndrome, or are you just playing it safe? Health and safety are among the most important considerations for travelers at this stage of the pandemic. They have to be included in any assessment of the risks and rewards of a vacation this year.

“It’s important to determine which variables are most important to you and your travel companions,” says Daniel Durazo, a spokesman for Allianz Travel , a travel insurance company.

If you want to err on the side of caution, you may want to stay in your cave for a little while. If the public health threat abates and you’re still struggling with travel anxiety, Bregman says, a combination of medication and therapy can help. And nothing puts you at ease quite like a carefully prepared plan, particularly when it comes to an upcoming trip.

Fortunately, our reluctance to travel is likely to fade with the pandemic, according to experts.

“However much Zoom and other technologies have advanced, the sights and smells of new places bring an excitement and opportunity for learning from others that can’t be replaced,” says Martha Merritt , the University of Richmond’s dean of international education. “As global travel becomes possible once again, I think many of us will return to it.”

Many — but not all.

Read more from Travel :

Read past Navigator columns here

Your Life at Home

The Post’s best advice for living during the pandemic.

Health & Wellness: What to know before your vaccine appointment | Creative coping tips | What to do about Zoom fatigue

Newsletter: Sign up for Eat Voraciously — one quick, adaptable and creative recipe in your inbox every Monday through Thursday.

Parenting: Guidance for vaccinated parents and unvaccinated kids | Preparing kids for “the return” | Pandemic decision fatigue

Food: Dinner in Minutes | Use the library as a valuable (and free) resource for cookbooks, kitchen tools and more

Arts & Entertainment: Ten TV shows with jaw-dropping twists | Give this folk rock duo 27 minutes. They’ll give you a musically heartbreaking world.

Home & Garden: Setting up a home workout space | How to help plants thrive in spring | Solutions for stains and scratches

Travel: Vaccines and summer travel — what families need to know | Take an overnight trip with your two-wheeled vehicle

Popular Services

- Patient & Visitor Guide

Committed to improving health and wellness in our Ohio communities.

Health equity, healthy community, classes and events, the world is changing. medicine is changing. we're leading the way., featured initiatives, helpful resources.

- Refer a Patient

5 tips to ease pre-travel anxiety

Author: Cheryl Carmin, PhD

- Health and Wellness

- Mental and Behavioral Health

- Neurological Institute

- Try to figure out what it is about travel that is making you anxious. What are you saying to yourself? Can you identify your “What ifs?” Once you’re able to understand what you’re afraid of, ask yourself if the fear is realistic. Even if your worst-case scenario is something catastrophic, does the very small likelihood of its occurrence outweigh the severity?

- If you have traveled before, what has your experience been? Did any of the things you’re worrying about happen? If they did, how did you manage? There’s a good chance you’re not giving yourself credit for being an effective and resilient problem solver.

- Is the over-planning, list-making or other strategies really helping? Everyone has their own way of preparing for travel. Making others conform to your way may cause arguments with your traveling companions and more stress.

- Do you have strategies to help you to relax? Slow, paced breathing is one strategy that many people find to be effective. Try an app for your smart phone, or one of the free relaxation recordings available from Ohio State’s Center for Integrative Medicine that help you to restore your calm equilibrium.

- Don’t skip the self-care activities. Just because you may think you’re in a time crunch the week before a trip, build in time for exercise. Physical activity is a great way to manage stress. Pamper yourself. A haircut or a manicure may be an important part of your pre-travel preparation to help you de-stress.

What provokes anxiety differs from person to person. This is definitely not a ‘one size fits all’ phenomenon. It may be useful to separate out if you’re afraid of the act of traveling or the destination.

- Our mental health experts are here to help you. Learn more

More from Ohio State

Anxious about returning to the post-pandemic world? You’re not alone

Mask or no mask? Is a hug OK? For some who have been diligent in avoiding social gatherings and crowds for so long, this return to a normal lifestyle is filled with anxiety.

Cicadas bugging you? You’re not alone. Read these tips to dial down your anxiety

Just the thought of billions of cicadas tunneling their way up to the surface is enough to seriously creep out people – some to the point where they won’t go in their backyard or to a park.

Facing Memorial Day grief, and why this year may be harder

This Memorial Day, some may be feeling the weight of loss more deeply. Memorial Day is about setting aside time to remember those we’ve lost. Giving ourselves space to feel the emotions that accompany those memories is important.

Visit Ohio State Health & Discovery for more stories on health, wellness, innovation, research and science news from the experts at Ohio State.

Check out health.osu.edu

Subscribe. Get just the right amount of health and wellness in your inbox.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Post-pandemic and post-traumatic tourism behavior

a Department of Integrated Resort and Tourism Management, Faculty of Business Administration, University of Macau, China

Jinyoung Im

b School of Hospitality and Tourism Management, Spears School of Business, Oklahoma State University, United States

Kevin Kam Fung So

Associated data, introduction.

The COVID-19 pandemic, a multi-faceted crisis and a potentially traumatic event, is both a personally impactful event and a globally shared experience (e.g., Williamson et al., 2021 ). However, exposure to highly stressful events can also be a precursor to post-traumatic growth, the positive personal growth people experience when emerging from adversity ( Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004 ). In this perspective article, we aim to examine post-pandemic tourism behavior through the theoretical lens of post-traumatic growth. Casting COVID-19 as a catalyst for personal growth, we explore how post-pandemic travel and tourism activities manifest as the consequences of post-traumatic growth as well as the means for it. More importantly, we attempt to understand how post-traumatic growth and post-pandemic restructured assumptions about travel and tourism jointly influence the post-pandemic and post-traumatic tourism behavior.

Prior literature recognizes five major domains of post-traumatic growth: changed priorities and a deeper appreciation of life; development of closer social relationships; resilience; openness to new life possibilities; and greater existential or spiritual growth ( Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004 ). Post-traumatic growth entails a process of shattering the old “assumptive world,”—one's general understanding of the world—and restructuring the fundamental components of a new one in its place. The COVID-19 pandemic has been a seismic force of disruption to the act of travel. Restrictions in movements, border closures, cancellations of flights and other transportation means, and closures of tourist destinations have drastically shattered the pre-pandemic assumptions people held for travel and tourism. The pandemic also accelerated some geopolitical trends such as de-globalization, isolationism, and regionalism. In this research, we present a set of seemingly opposing behavioral tendencies in an attempt to capture the imprints of post-traumatic growth and restructured assumptions about travel on post-pandemic tourism behaviors. Namely, rebound and retreat, connectedness and estrangement, and self-transcendence and self-diminishment in post-pandemic and post-traumatic tourism behavior.

Rebound and retreat

Post-traumatic growth reflects coping with the lingering distress of the trauma and attempts at psychological survival ( Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004 ). In the post-pandemic era, travel and tourism patterns are likely to mirror post-traumatic growth's initial stage of return to baseline, recovery, and reset. As the pandemic abates and travel restrictions start to ease, a sudden surge in travel and tourism activities in the initial post-COVID period is expected. For example, on June 11, 2021, more than two million people screened through U.S. airport security checkpoints in a single day, which more than doubled the number in April 2020 and was close to 75% of the volume recorded on the same day in 2019 ( Koenig, 2021 June ). The predicted sudden and dramatic rebound in travel demand is vividly described as “revenge travel” in the media ( Bologna, 2021 April ). Such burning urge to travel also has psychological roots, signifying travelers' need for retribution against COVID-19 and a regained sense of control to return to normalcy.

As tourism rebounds, retreat behavior in tourism is also likely to be salient. With a heightened sense of vulnerability induced by the pandemic, retreat behavior of the “6 foot-tourism world,” or the disconnection between tourism spaces and reframing tourism activities on a local scale ( Lapointe, 2020, p. 636 ), manifests in behaviors such as maintaining social distancing from other travelers, avoiding overly popular tourism destinations, choosing less-known tourism destinations, and preferring regional travels. Solitary travel experiences such as camping in remote areas ( Bhalla et al., 2021 ) and travel centered on retreat experience ( Wang et al., 2021 ) are likely to continue to gain popularity after the pandemic. Solo travels that are unconstrained by interpersonal decision making and motivated by solitary experience are on the rise as well ( Shin et al., 2022 ).

Connectedness and estrangement

One of the most noticeable domains of post-traumatic growth is developing closer relationships with others ( Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004 ). The relationship domain of post-traumatic growth will be particularly salient in the post-COVID era. The COVID-related movement restriction measures, such as suspension of social gatherings and travel bans, have resulted in a sense of social disconnectedness ( Kato et al., 2020 ). Visiting immediate family and friends is likely to be a strong travel motivation that drives the first wave of travel in the immediate wake of the pandemic. Increasing demand in multi-generational travel may also be expected.

While the tourism industry will benefit from post-traumatic growth in building stronger interpersonal relationships, of particular significance is the simultaneous social estrangement induced by the pandemic at interpersonal, community, national, and international levels. At the interpersonal level, moments of subtle hostility and belligerence are found in various leisure situations. For example, a visitor without a mask assaulted a native elderly person in Hawaii ( Bourlin, 2021 March ). At the destination level, residents' “us versus them” mentality has been reignited. Many countries have banned cruise ship arrivals at their ports ( Fox, 2021 February ). At the national and international levels, deglobalization, isolationism, and the regionalism of tourism ( Brouder et al., 2020 ) will have opposing effects on tourism development. Tourists may also display xenophobia that leads to reduced international travel, hesitation to try foreign food, and greater preference for using a travel agency and group travel ( Kock et al., 2019 ). The localized and regionalized travel trends due to nationalistic thoughts, distrust, anxiety, and even hostility have intensified during the pandemic ( Brouder et al., 2020 ) and may have a long-term adverse effect on post-pandemic travel and tourism.

Self-transcendence and self-diminishment

Catastrophic events drastically alter people's outlooks in life as people make sense of events, search for meaning and purpose, and seek spiritual growth ( Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004 ). Given its severity, the COVID-19 pandemic could be considered as existential hapax, a crucial moment of life and an intense experience that led to significant physical, emotional, and spiritual transformation ( Matteucci, 2021 ). In the post-pandemic era, travel for purpose and morality may become more prevalent as people engage in a deeper introspective reflection in searching for purpose and constructing a revised life narrative. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated many social issues such as unequal access to health care, poverty, food insecurity, racial injustice, and more. A notable phenomenon during the pandemic is the occurrence of large-scale protests despite the risk of spreading the virus ( Berger, 2020 October ). New forms of activism-based tourism are emerging, such as justice tourism and protest tourism ( Guia, 2021 ). For example, in August 2020, Portland, Oregon in the United States saw an increase in the number of tourists who came to visit the sites of the Black Lives Matter protests ( Gallivan, 2020 August ). The focus of alternative tourism is social eudaimonia that highlights compassion, ethics, and collective well-being ( Matteucci et al., 2021 ).

The Covid-19 pandemic induces direct health threats as well as secondary stressful events stemming from pandemic-related circumstances such as financial distress, separation from one's social support system, and a prolonged pandemic without an end in sight ( Williamson et al., 2021 ). Such wide-spread stressors can lead to negative psychological responses such as depersonalization (a sense of detachment from self, others, and the world) and a sense of self worthlessness ( Williamson et al., 2021 ). Such self-diminishment tendencies may manifest in tourism behaviors such as lack of interest in travel and reduced enjoyment when they do.

This research offers a post-traumatic growth theoretical perspective of post-pandemic tourism behavior ( Fig. 1 ). While the post-pandemic and post-traumatic tourism behaviors are presented as outcomes of both pandemic induced and post-traumatic induced changes, it is important to recognize that the two forces are often intertwined. For example, pandemic-induced risk reduction (retreat) behaviors are conceptually related to post-traumatic growth. While current literature predominately approaches post-traumatic growth as a general measure (e.g., the post-traumatic growth inventory, Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996 ; the traumatic life events questionnaire, Kubany, 2004 ), this research demonstrates that trauma-specific restructured assumptions might interact with the generic domains of post-traumatic growth to bear on domain-specific (i.e., travel and tourism) post-traumatic growth.

A conceptual framework of post-pandemic post-traumatic tourism behavior.

This research may offer implications for other crises that threaten tourism such as natural disasters, terrorism, and military conflicts. Miao et al. (2021) provided a terror management perspective of COVID-19 travel and tourism behavior. The post-traumatic growth perspective offered by this research extends the literature by portraying post-pandemic travel and tourism behavior as conscious efforts against mortality. Different degrees of such traumatic events experienced by individuals may manifest in different tourism behaviors. For example, people with a lower degree of risk perception toward COVID-19 intend to travel longer and more frequently ( Kim et al., 2021 ).

Future research can build on the theoretical foundations laid out by this study to test the relationships between post-pandemic tourism behavior and post-traumatic growth. Another fruitful inquiry is to what extent post-pandemic travels trigger feelings of traumatic growth and which forms of travel are most effective in inducing such effects. In addition, future researchers can take a qualitative approach through in-depth interviews and personal narratives to explore the connections between post-pandemic tourism activities and post-traumatic growth.

Declaration of competing interest

Biographies.

Li Miao is a professor at University of Macau, focusing on travel and tourism behavior.

Jinyoung Im is an assistant professor at Oklahoma State University, interested in consumer

Kevin Kam Fung So is an associate professor at Oklahoma State University, interested in

services marketing.

Yan Cao is a doctoral candidate at Oklahoma State University, interested in consumer behavior.

Associate editor: Jeroen Nawijn

Appendix A Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103410 .

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Post-pandemic and post-traumatic tourism behavior.

- Berger M. The Washington Post; 2020, October 2. The pandemic is an ear of protests—And protest restrictions. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2020/10/02/coronavirus-pandemic-demonstrations-protest-restrictions/

- Bhalla R., Chowdhary N., Ranjan A. Spiritual tourism for psychotherapeutic healing post COVID-19. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing. 2021:1–13. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bologna C. Huffpost; 2021, April 6. ‘Revenge travel’ will be all the rage over the next few years. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/revenge-travel-future_l_6052b724c5b638881d29a416

- Bourlin N. Sfgate; 2021, March 27. ‘Your vacation is my home’: Hawaii's residents are speaking out against tourists behaving badly. https://www.sfgate.com/hawaii/article/hawaii-residents-locals-tourists-behaving-badly-16056414.php

- Brouder P., Teoh S., Salazar N., Mostafanezhad M., Pung J., Lapointe D., Desbiolles F., Haywood M., Hall C.M., Clausen H. Reflections and discussions: tourism matters in the new normal post COVID-19. Tourism Geographies. 2020; 22 (3):735–746. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fox A. Travel + Leisure; 2021, February 28. Canada extends ban on cruise ships until at least 2022. https://www.travelandleisure.com/cruises/canada-bans-cruise-ships-until-2022

- Gallivan J. Portland Tribune; 2020, August. Wish you were here: Portland sees surge in protest tourism. https://pamplinmedia.com/pt/9-news/475933-384307-wish-you-were-here-portland-sees-surge-in-protest-tourism

- Guia J. Conceptualizing justice tourism and the promise of posthumanism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2021; 29 (2–3):502–519. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kato T.A., Sartorius N., Shinfuku N. Forced social isolation due to COVID-19 and consequent mental health problems: Lessons from hikikomori. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2020; 74 (9):506–507. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim E.E.K., Seo K., Choi Y. Compensatory travel post COVID-19: Cognitive and emotional effects of risk perception. Journal of Travel Research. 2021:1–15. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kock F., Josiassen A., Assaf A.G. The xenophobic tourist. Annals of Tourism Research. 2019; 74 :155–166. [ Google Scholar ]

- Koenig D. AP News; 2021, June. Travel rebound: 2 million people go through US airports. https://apnews.com/article/coronavirus-pandemic-technology-health-lifestyle-travel-a2b3260a8633c2404dab44507b5de811

- Kubany E. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles, CA: 2004. Traumatic life events questionnaire and PTSD screening and diagnostic scale. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lapointe D. Reconnecting tourism after COVID-19: The paradox of alterity in tourism areas. Tourism Geographies. 2020; 22 (3):633–638. [ Google Scholar ]

- Matteucci X. Tourism Recreation Research; 2021. Existential hapax as tourist embodied transformation; pp. 1–5. [ Google Scholar ]

- Matteucci X., Nawijn J., von Zumbusch J. A new materialist governance paradigm for tourism destinations. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2021:1–16. [ Google Scholar ]

- Miao L., Im J., Fu X., Kim H., Zhang Y.E. Proximal and distal post-COVID travel behavior. Annals of Tourism Research. 2021; 88 [ Google Scholar ]

- Shin H., Nicolau J.L., Kang J., Sharma A., Lee H. Travel decision determinants during and after COVID-19: The role of tourist trust, travel constraints, and attitudinal factors. Tourism Management. 2022; 88 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tedeschi R.G., Calhoun L.G. The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996; 9 (3):455–471. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tedeschi R.G., Calhoun L.G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry. 2004; 15 (1):1–18. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang Y.C., Chen P.J., Shi H., Shi W. Travel for mindfulness through Zen retreat experience: A case study at Donghua Zen Temple. Tourism Management. 2021; 83 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Williamson R., Hoeboer C., Primasari I., Qing Y., Coimbra B., Hovnanyan A., Grace E., Olff M. Symptom networks of COVID-19 related versus other potentially traumatic events in global sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2021; 84 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

Post-Pandemic Anxiety: Life is Returning to Normal, So Why Do You Feel Anxious?

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share on Email

You’re fully vaccinated, New York is reopening, and life is getting back to normal. So, why are you anxious? Instead of joy, you feel overwhelmed, stressed, and can’t stop asking yourself: How should I behave around others? Should I continue to physically distance? Should I shake a stranger’s hand? Do I even want to?

After more than a year of social distancing and without knowing who is fully vaccinated, returning to ‘normal’ may feel scary, especially if you already live with anxiety, according to Dr. Susan Evans, Professor of Psychology in Clinical Psychiatry. “Anxious individuals worry,” Dr. Evans says. “Whenever there is uncertainty about the future, there is the likelihood for increased worry and anxiety,” she says.

Are you a productive or unproductive worrier?

Worry is a ruminative process that takes the form of ‘What if…,’ which is usually some negative and often catastrophic prediction about something bad happening, Dr. Evans explains. During the pandemic, much of people’s worry has been safety related and presented as questions such as, “’What if I get sick…?” “What if I wasn’t careful enough…?” “What if someone in my family gets infected?”

The pandemic and its imperative to socially distance have also triggered or intensified social anxiety, which breeds worry about how others perceive you and leads to questions like, “What if they don’t like me…?” “What if I say something stupid…?”

There has also been an upswing in overall anxiety about job safety, going out of business, loss of income, or even housing. “People are more worried than ever about their financial situation,” Dr. Evans says. Longstanding and newly aggravated societal, cultural, and political problems have multiplied this anxiety, she says. “Health and economic disparities, social injustice, and gun violence are all serious matters that people are worried about.”

The COVID-19 anxiety cycle

Despite growing optimism about the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the rollout of vaccines that are proving to protect against some variants, television news and social media focus on the negative: how vaccine resistance may undermine efforts to achieve ‘herd immunity;’ rising infections from COVID variants; and concerns about the longevity of vaccine-derived immunity. “For anxious individuals, the default position is to ruminate on worst case scenarios,” Dr. Evans says. “Rumination leads to more anxiety and so it becomes a vicious cycle.”

To interrupt the cycle, it helps to understand the difference between productive and unproductive worrying, Dr. Evans explains. “Unproductive worry is about focusing on things that might happen and spinning in your head about it. Productive worry is asking the question, “Is there anything I can do about this now?” and then taking the appropriate action.”

For example, ruminating and feeling anxious over whether you can handle returning to your office is unproductive worry, whereas deciding to take one day at a time and focus on the present moment is productive. “It is important to address the problem of avoiding life and engage in work and other activities that are considered reasonable and safe,” she says.

Similarly, worrying about your risk of catching COVID (very low if you’re fully vaccinated) now that states and localities are relaxing most pandemic-related capacity restrictions, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has given fully vaccinated people the green light to go mask-less--except in certain crowded settings and venues--when enjoying other outdoor activities alone or with family members, is unproductive, whereas taking action to continue wearing a mask and socially distance is productive.

Taking small, positive steps

Knowing all of this may help lessen--but not erase--your anxiety and depression, which may linger for a while. In the meantime, Dr. Evans suggests easing back into life at your own comfort level.

“If you have been isolating and have not been outdoors, start with small steps such as walking to the corner,” she advises. “Practice building on this experience as your confidence grows. Keep in mind that having one foot out of your comfort zone is a good thing because it suggests you are stretching yourself.”

Practicing mindfulness is a useful skill to cope with general anxiety, she continues. “Mindfulness is about paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment. Paying attention to the present moment is the opposite of ruminating and being stuck in one’s head in unproductive worry.”

To cope with specific anxiety about returning to work, school or socializing, Dr. Evans suggests building your stress resistance by getting enough sleep, exercising, practicing yoga and or meditation, or talking to a friend.

She also warns against excessive intake of the media, particularly social media, as well as over-indulging in alcohol or food. “Anxious individuals may use substances to avoid the way they are feeling so be careful of excessive alcohol or other emotion numbing strategies such as overeating.”

As you work through your anxiety, try to remember that you are not alone. The pandemic has struck everyone in one way or another and many people may be feeling as anxious as you.

If you have previously struggled with anxiety or depression, then you may want to seek professional help. You may join a group therapy program to work on your social anxiety. Whatever you do, try to practice self-compassion and care, and don’t feel compelled to hide your feelings. Sharing them will encourage others to share theirs, which may help you to feel better and less alone in the long run.

Related Links

Back to News

In This Article

Clinical service.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 19 June 2024

Chronic post-COVID neuropsychiatric symptoms persisting beyond one year from infection: a case-control study and network analysis

- Steven Wai Ho Chau ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2986-8677 1 , 2 ,

- Timothy Mitchell Chue 1 ,

- Rachel Ngan Yin Chan 1 , 2 ,

- Yee Lok Lai ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0004-1002-8805 1 ,

- Paul W. C. Wong 3 ,

- Shirley Xin Li 4 ,

- Yaping Liu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2015-8775 1 , 5 ,

- Joey Wing Yan Chan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2692-2666 1 , 2 ,

- Paul Kay-sheung Chan 6 ,

- Christopher K. C. Lai ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8591-5944 6 ,

- Thomas W. H. Leung 7 &

- Yun Kwok Wing ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5745-5474 1 , 2

Translational Psychiatry volume 14 , Article number: 261 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

360 Accesses

17 Altmetric

Metrics details

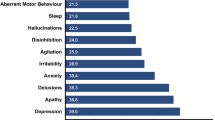

- Psychiatric disorders

Our study aims to delineate the phenotypes of chronic neuropsychiatric symptoms among adult subjects recovering from their first COVID that occurred more than one year ago. We also aim to explore the clinical and socioeconomic risk factors of having a high loading of chronic neuropsychiatric symptoms. We recruited a post-COVID group who suffered from their first pre-Omicron COVID more than a year ago, and a control group who had never had COVID. The subjects completed app-based questionnaires on demographic, socioeconomic and health status, a COVID symptoms checklist, mental and sleep health measures, and neurocognitive tests. The post-COVID group has a statistically significantly higher level of fatigue compared to the control group ( p < 0.001). Among the post-COVID group, the lack of any COVID vaccination before the first COVID and a higher level of material deprivation before the COVID pandemic predicts a higher load of chronic post-COVID neuropsychiatric symptoms. Partial correlation network analysis suggests that the chronic post-COVID neuropsychiatric symptoms can be clustered into two major (cognitive complaints -fatigue and anxiety-depression) and one minor (headache-dizziness) cluster. A higher level of material deprivation predicts a higher number of symptoms in both major clusters, but the lack of any COVID vaccination before the first COVID only predicts a higher number of symptoms in the cognitive complaints-fatigue cluster. Our result suggests heterogeneity among chronic post-COVID neuropsychiatric symptoms, which are associated with the complex interplay of biological and socioeconomic factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Long COVID prevalence and impact on quality of life 2 years after acute COVID-19

Dimensional structure of one-year post-COVID-19 neuropsychiatric and somatic sequelae and association with role impairment

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and carer mental health: an international multicentre study