What are the contents of the Golden Record?

The contents of the record were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University, et. al. Dr. Sagan and his associates assembled 115 images and a variety of natural sounds, such as those made by surf, wind and thunder, birds, whales, and other animals. To this they added musical selections from different cultures and eras, and spoken greetings from Earth-people in fifty-five languages, and printed messages from President Carter and U.N. Secretary General Waldheim.

The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space.

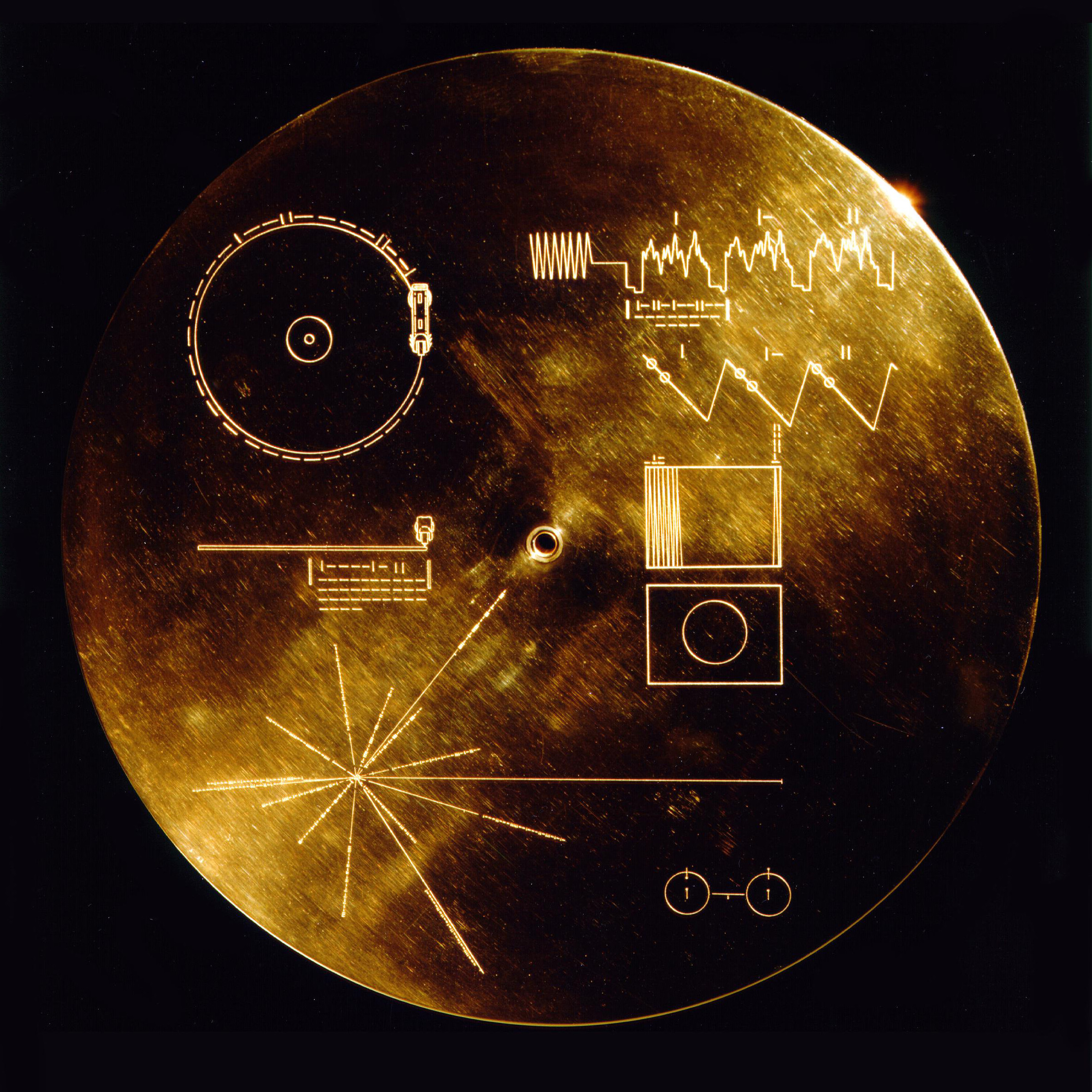

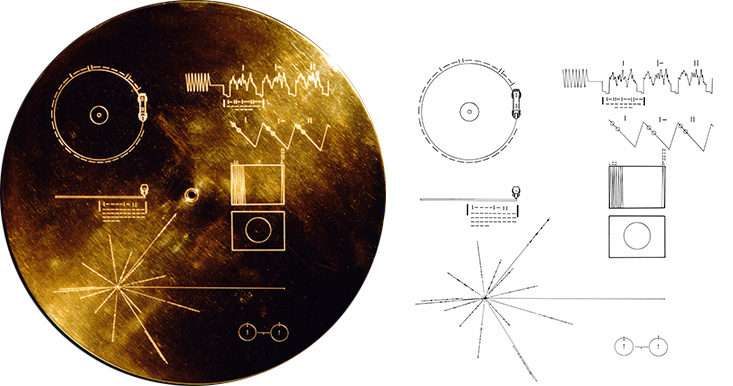

Each record is encased in a protective aluminum jacket, together with a cartridge and a needle. Instructions, in symbolic language, explain the origin of the spacecraft and indicate how the record is to be played. The 115 images are encoded in analog form.

Sounds and Music

The remainder of the record is in audio, designed to be played at 16-2/3 revolutions per minute. It contains the spoken greetings , beginning with Akkadian, which was spoken in Sumer about six thousand years ago, and ending with Wu, a modern Chinese dialect. Following the section on the sounds of Earth , there is an eclectic 90-minute selection of music , including both Eastern and Western classics and a variety of ethnic music. Once the Voyager spacecraft leave the solar system (by 1990, both will be beyond the orbit of Pluto), they will find themselves in empty space. It will be forty thousand years before they make a close approach to any other planetary system. As Carl Sagan has noted, "The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space. But the launching of this bottle into the cosmic ocean says something very hopeful about life on this planet."

The definitive work about the Voyager record is "Murmurs of Earth" by Executive Director, Carl Sagan, Technical Director, Frank Drake, Creative Director, Ann Druyan, Producer, Timothy Ferris, Designer, Jon Lomberg, and Greetings Organizer, Linda Salzman. Basically, this book is the story behind the creation of the record, and includes a full list of everything on the record. "Murmurs of Earth", originally published in 1978, was reissued in 1992 by Warner News Media with a CD-ROM that replicates the Voyager record. Unfortunately, this book is now out of print, but it is worth the effort to try and find a used copy or browse through a library copy.

Voyager Will Carry "Earth Sounds" Record

On the chance that someone is out there, NASA has approved tie placement of a phonograph record on each of two planetary spacecraft being readied far launch next month to the outer reaches of the solar system.

Discover More Topics From NASA

Our Solar System

What Is on Voyager’s Golden Record?

From a whale song to a kiss, the time capsule sent into space in 1977 had some interesting contents

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino

Senior Editor

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Voyager-records-631.jpg)

“I thought it was a brilliant idea from the beginning,” says Timothy Ferris. Produce a phonograph record containing the sounds and images of humankind and fling it out into the solar system.

By the 1970s, astronomers Carl Sagan and Frank Drake already had some experience with sending messages out into space. They had created two gold-anodized aluminum plaques that were affixed to the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecraft. Linda Salzman Sagan, an artist and Carl’s wife, etched an illustration onto them of a nude man and woman with an indication of the time and location of our civilization.

The “Golden Record” would be an upgrade to Pioneer’s plaques. Mounted on Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, twin probes launched in 1977, the two copies of the record would serve as time capsules and transmit much more information about life on Earth should extraterrestrials find it.

NASA approved the idea. So then it became a question of what should be on the record. What are humanity’s greatest hits? Curating the record’s contents was a gargantuan task, and one that fell to a team including the Sagans, Drake, author Ann Druyan, artist Jon Lomberg and Ferris, an esteemed science writer who was a friend of Sagan’s and a contributing editor to Rolling Stone .

The exercise, says Ferris, involved a considerable number of presuppositions about what aliens want to know about us and how they might interpret our selections. “I found myself increasingly playing the role of extraterrestrial,” recounts Lomberg in Murmurs of Earth , a 1978 book on the making of the record. When considering photographs to include, the panel was careful to try to eliminate those that could be misconstrued. Though war is a reality of human existence, images of it might send an aggressive message when the record was intended as a friendly gesture. The team veered from politics and religion in its efforts to be as inclusive as possible given a limited amount of space.

Over the course of ten months, a solid outline emerged. The Golden Record consists of 115 analog-encoded photographs, greetings in 55 languages, a 12-minute montage of sounds on Earth and 90 minutes of music. As producer of the record, Ferris was involved in each of its sections in some way. But his largest role was in selecting the musical tracks. “There are a thousand worthy pieces of music in the world for every one that is on the record,” says Ferris. I imagine the same could be said for the photographs and snippets of sounds.

The following is a selection of items on the record:

Silhouette of a Male and a Pregnant Female

The team felt it was important to convey information about human anatomy and culled diagrams from the 1978 edition of The World Book Encyclopedia. To explain reproduction, NASA approved a drawing of the human sex organs and images chronicling conception to birth. Photographer Wayne F. Miller’s famous photograph of his son’s birth, featured in Edward Steichen’s 1955 “Family of Man” exhibition, was used to depict childbirth. But as Lomberg notes in Murmurs of Earth , NASA vetoed a nude photograph of “a man and a pregnant woman quite unerotically holding hands.” The Golden Record experts and NASA struck a compromise that was less compromising— silhouettes of the two figures and the fetus positioned within the woman’s womb.

DNA Structure

At the risk of providing extraterrestrials, whose genetic material might well also be stored in DNA, with information they already knew, the experts mapped out DNA’s complex structure in a series of illustrations.

Demonstration of Eating, Licking and Drinking

When producers had trouble locating a specific image in picture libraries maintained by the National Geographic Society, the United Nations, NASA and Sports Illustrated , they composed their own. To show a mouth’s functions, for instance, they staged an odd but informative photograph of a woman licking an ice-cream cone, a man taking a bite out of a sandwich and a man drinking water cascading from a jug.

Olympic Sprinters

Images were selected for the record based not on aesthetics but on the amount of information they conveyed and the clarity with which they did so. It might seem strange, given the constraints on space, that a photograph of Olympic sprinters racing on a track made the cut. But the photograph shows various races of humans, the musculature of the human leg and a form of both competition and entertainment.

Photographs of huts, houses and cityscapes give an overview of the types of buildings seen on Earth. The Taj Mahal was chosen as an example of the more impressive architecture. The majestic mausoleum prevailed over cathedrals, Mayan pyramids and other structures in part because Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan built it in honor of his late wife, Mumtaz Mahal, and not a god.

Golden Gate Bridge

Three-quarters of the record was devoted to music, so visual art was less of a priority. A couple of photographs by the legendary landscape photographer Ansel Adams were selected, however, for the details captured within their frames. One, of the Golden Gate Bridge from nearby Baker Beach, was thought to clearly show how a suspension bridge connected two pieces of land separated by water. The hum of an automobile was included in the record’s sound montage, but the producers were not able to overlay the sounds and images.

A Page from a Book

An excerpt from a book would give extraterrestrials a glimpse of our written language, but deciding on a book and then a single page within that book was a massive task. For inspiration, Lomberg perused rare books, including a first-folio Shakespeare, an elaborate edition of Chaucer from the Renaissance and a centuries-old copy of Euclid’s Elements (on geometry), at the Cornell University Library. Ultimately, he took MIT astrophysicist Philip Morrison’s suggestion: a page from Sir Isaac Newton’s System of the World , where the means of launching an object into orbit is described for the very first time.

Greeting from Nick Sagan

To keep with the spirit of the project, says Ferris, the wordings of the 55 greetings were left up to the speakers of the languages. In Burmese , the message was a simple, “Are you well?” In Indonesian , it was, “Good night ladies and gentlemen. Goodbye and see you next time.” A woman speaking the Chinese dialect of Amoy uttered a welcoming, “Friends of space, how are you all? Have you eaten yet? Come visit us if you have time.” It is interesting to note that the final greeting, in English , came from then-6-year-old Nick Sagan, son of Carl and Linda Salzman Sagan. He said, “Hello from the children of planet Earth.”

Whale Greeting

Biologist Roger Payne provided a whale song (“the most beautiful whale greeting,” he said, and “the one that should last forever”) captured with hydrophones off the coast of Bermuda in 1970. Thinking that perhaps the whale song might make more sense to aliens than to humans, Ferris wanted to include more than a slice and so mixed some of the song behind the greetings in different languages. “That strikes some people as hilarious, but from a bandwidth standpoint, it worked quite well,” says Ferris. “It doesn’t interfere with the greetings, and if you are interested in the whale song, you can extract it.”

Reportedly, the trickiest sound to record was a kiss . Some were too quiet, others too loud, and at least one was too disingenuous for the team’s liking. Music producer Jimmy Iovine kissed his arm. In the end, the kiss that landed on the record was actually one that Ferris planted on Ann Druyan’s cheek.

Druyan had the idea to record a person’s brain waves, so that should extraterrestrials millions of years into the future have the technology, they could decode the individual’s thoughts. She was the guinea pig. In an hour-long session hooked to an EEG at New York University Medical Center, Druyan meditated on a series of prepared thoughts. In Murmurs of Earth , she admits that “a couple of irrepressible facts of my own life” slipped in. She and Carl Sagan had gotten engaged just days before, so a love story may very well be documented in her neurological signs. Compressed into a minute-long segment, the brain waves sound, writes Druyan, like a “string of exploding firecrackers.”

Georgian Chorus—“Tchakrulo”

The team discovered a beautiful recording of “Tchakrulo” by Radio Moscow and wanted to include it, particularly since Georgians are often credited with introducing polyphony, or music with two or more independent melodies, to the Western world. But before the team members signed off on the tune, they had the lyrics translated. “It was an old song, and for all we knew could have celebrated bear-baiting,” wrote Ferris in Murmurs of Earth . Sandro Baratheli, a Georgian speaker from Queens, came to the rescue. The word “tchakrulo” can mean either “bound up” or “hard” and “tough,” and the song’s narrative is about a peasant protest against a landowner.

Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode”

According to Ferris, Carl Sagan had to warm up to the idea of including Chuck Berry’s 1958 hit “Johnny B. Goode” on the record, but once he did, he defended it against others’ objections. Folklorist Alan Lomax was against it, arguing that rock music was adolescent. “And Carl’s brilliant response was, ‘There are a lot of adolescents on the planet,’” recalls Ferris.

On April 22, 1978, Saturday Night Live spoofed the Golden Record in a skit called “Next Week in Review.” Host Steve Martin played a psychic named Cocuwa, who predicted that Time magazine would reveal, on the following week’s cover, a four-word message from aliens. He held up a mock cover, which read, “Send More Chuck Berry.”

More than four decades later, Ferris has no regrets about what the team did or did not include on the record. “It means a lot to have had your hand in something that is going to last a billion years,” he says. “I recommend it to everybody. It is a healthy way of looking at the world.”

According to the writer, NASA approached him about producing another record but he declined. “I think we did a good job once, and it is better to let someone else take a shot,” he says.

So, what would you put on a record if one were being sent into space today?

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/megan.png)

Megan Gambino | | READ MORE

Megan Gambino is a senior web editor for Smithsonian magazine.

11 Pieces of Media on the Voyager Golden Record

By michele debczak | apr 11, 2021.

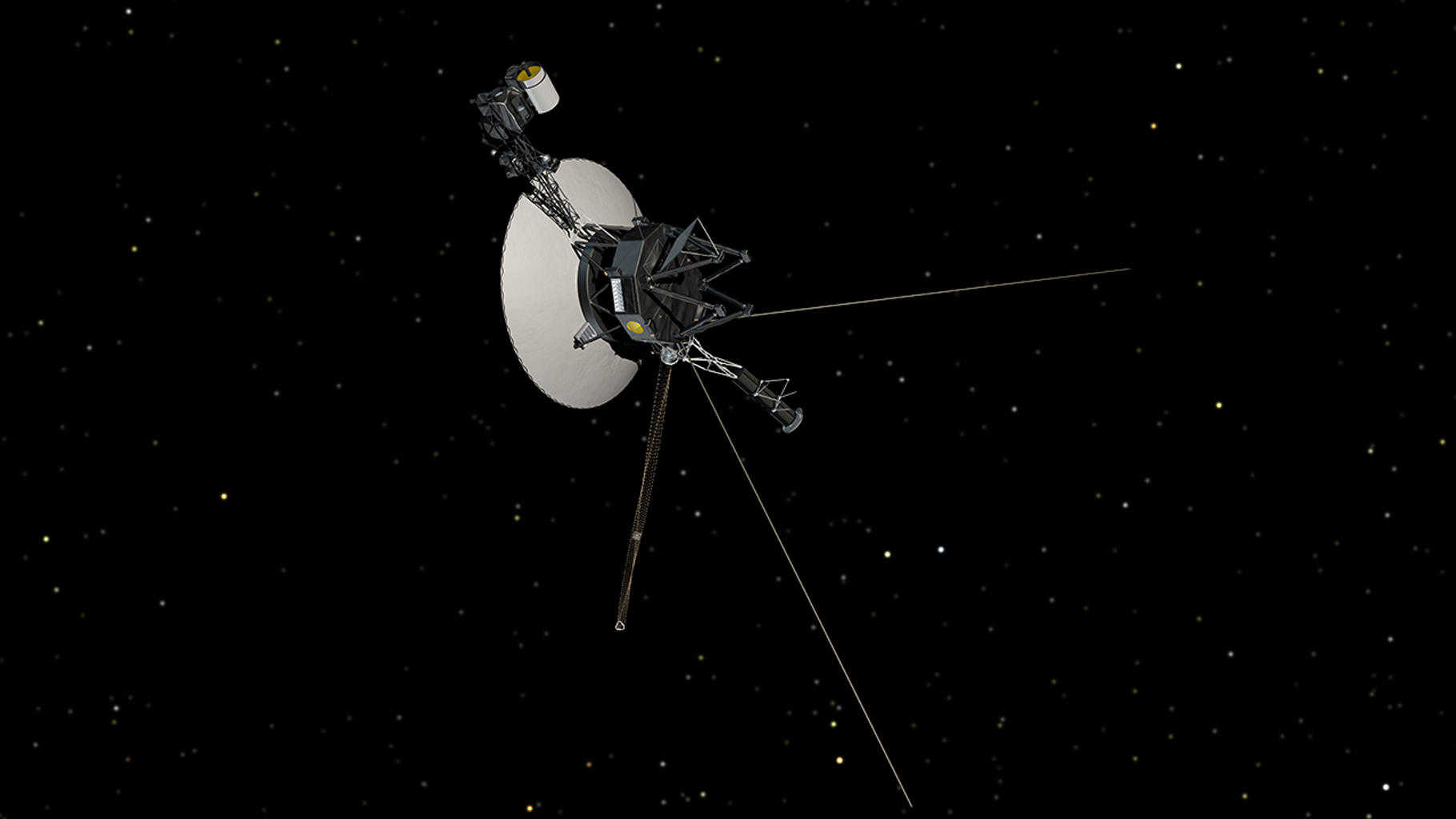

At this moment, two gold-plated copper records are hurtling through space, speeding beyond our solar system. The Voyager 1 and 2 probes launched in 1977 , and they’ve since traveled billions of miles from Earth. They are currently the loneliest human-made objects in the universe—and they may stay that way forever—but they were built to make a connection.

The purpose of NASA ’s Voyager mission is to illustrate life on Earth to any intelligent aliens that come across the spacecraft. The records on board contain media selected by a committee chaired by scientist Carl Sagan. If extraterrestrials can use the instructions engraved on the disc's cover to access its contents, they’ll be exposed to animal noises, classical music, and photographs of people from around the world. Here are some pieces of media that were chosen to represent our planet.

1. Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony

Ludwig van Beethoven is one of many classical artists representing the music of Earth on the Voyager record. In addition to his Fifth Symphony , the composer’s String Quartet No. 13, Opus 130, is also included on the track list.

2. Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode”

Though there are many musical compositions on the Voyager Golden Record , the inclusion of “Johnny B. Goode” stirred controversy. Critics claimed rock n’ roll was too adolescent for a project of such significance. Carl Sagan responded by saying, “There are a lot of adolescents on the planet.”

3. A Mandarin Greeting and Invitation

The Voyager project recorded UN delegates from around the world saying greetings in 54 different languages. Most are straightforward, but the Mandarin message includes an invitation. Translated to English, it says: "Hope everyone's well. We are thinking about you all. Please come here to visit when you have time."

4. Humpback Whale Songs

The greetings section of the record features one language that doesn’t belong to humans. Interspersed between the spoken audio clips are the sounds of singing humpback whales . There’s a reason whales were included with the greetings rather than the other animal noises on the record—it was the committee’s way of acknowledging that humans aren’t the only intelligent life on Earth.

5. The UN Building

The Voyager committee chose the UN Building to represent modern urban architecture. The record includes two images of the New York City skyscraper, both taken at the same angle. One depicts the structure during the day and the other shows it at night .

6. A Traffic Jam

The Voyager record highlights many technological marvels from the time it was made, including a rocket and an airplane. The photo of a traffic jam in Thailand that was included may seem less impressive, but it accurately depicts how we use cars on our planet.

7. A Bulgarian Folk Song

The Voyager committee wanted the record's music to represent a wide range of eras and cultures. One track, titled "Izlel je Delyo Hagdutin," is a traditional folk song from Bulgaria . Sung by Valya Balkanska, it’s about a famous rebel leader from the country’s history. Folk music from Azerbaijan, Georgia, and the Navajo people also made it onto the compilation.

8. Ann Druyan’s Brainwaves

While working on the Voyager committee, Ann Druyan had the idea to record her brainwaves, turn them into audio, and copy them onto the record. She spent an hour hooked up to electrical impulse-measuring systems while thinking various thoughts, including what it’s like to fall in love. She and Sagan—her collaborator on the Voyager record project—had recently gotten engaged.

9. A Map of the Solar System

The Voyager mission is designed to travel far, but it will always hold evidence of where it came from. One of the images on the record shows a picture of our solar system with a map illustrating Earth’s location.

10. People Eating

Some human behaviors are tricky to capture in one image. To show the different ways people consume food and drink, the Voyager committee included a photo of someone licking ice cream, someone else biting into a sandwich, and a third person pouring water into their mouth.

11. A Morse Code Message

Another type of communication represented on the Voyager record is Morse code . The message translates to the Latin saying ad astra per aspera , or “to the stars through hard work.”

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

The Voyager Golden Record Finally Finds An Earthly Audience

Alexi Horowitz-Ghazi

The Voyager Golden Record remained mostly unavailable and unheard, until a Kickstarter campaign finally brought the sounds to human ears. Ozma Records/LADdesign hide caption

The Voyager Golden Record remained mostly unavailable and unheard, until a Kickstarter campaign finally brought the sounds to human ears.

The Golden Record is basically a 90-minute interstellar mixtape — a message of goodwill from the people of Earth to any extraterrestrial passersby who might stumble upon one of the two Voyager spaceships at some point over the next couple billion years.

But since it was made 40 years ago, the sounds etched into those golden grooves have gone mostly unheard, by alien audiences or those closer to home.

"The Voyager records are the farthest flung objects that humans have ever created," says Timothy Ferris, a veteran science and music journalist and the producer of the Golden Record. "And they're likely to be the longest lasting, at least in the 20th century."

In the late 1970s, Ferris was recruited by his friend, astronomer Carl Sagan, to join a team of scientists, artists and engineers to help create two engraved golden records to accompany NASA's Voyager mission — which would eventually send a pair of human spacecraft beyond the outer rings of the solar system for the first time in history.

Carl Sagan And Ann Druyan's Ultimate Mix Tape

Ferris was tasked with the technical aspects of getting the various media onto the physical LP, and with helping to select the music. In addition to greetings in dozens of languages and messages from leading statesmen, the records also contained a sonic history of planet Earth and photographs encoded into the record's grooves. But mostly, it was music.

"We were gathering a representation of the music of the entire earth," Ferris says. "That's an incredible wealth of great stuff."

Ferris and his colleagues worked together to sift through Earth's enormous discography to decide which pieces of sound would best represent our planet. They really only had two criteria: "One was: Let's cast a wide net. Let's try to get music from all over the planet," he says. "And secondly: Let's make a good record."

That meant late nights of listening sessions while "almost physically drowning in records," Ferris says.

The final selection, which was engraved in copper and plated in gold, included opera, rock 'n' roll, blues, classical music and field recordings selected by ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax .

When Voyager 1 and its identical sister craft Voyager 2 launched in 1977, each carried a gold record titled T he Sounds Of Earth that contained a selection of recordings of life and culture on Earth. The cover contains instructions for any extraterrestrial being wishing to play the record. NASA/Getty Images hide caption

When Voyager 1 and its identical sister craft Voyager 2 launched in 1977, each carried a gold record titled T he Sounds Of Earth that contained a selection of recordings of life and culture on Earth. The cover contains instructions for any extraterrestrial being wishing to play the record.

Ferris says that from the very start, many people on the production team expected and hoped for the record to be commercially released soon after the launch of Voyager.

"Carl Sagan tried to interest labels in releasing Voyager," Ferris says. "It never worked."

Ferris says that's likely because the music rights were owned by several different record labels who were hesitant to share the bill. So — except for a limited CD-ROM release in the early 1990s — the record went largely unheard by the wider world.

David Pescovitz, an editor at technology news website Boing Boing and a research director at the nonprofit Institute for the Future, was seven years old when the Voyager spacecraft launched.

"When you're seven years old and you hear that a group of people created a phonograph record as a message for possible extraterrestrials and launched it on a grand tour of the solar system," says Pescovitz, "it sparks the imagination."

A couple years ago, Pescovitz and his friend Tim Daly, a record store manager at Amoeba Music in San Francisco, decided to collaborate on bringing the Golden Record to an earthbound audience.

Pescovitz approached his former graduate school professor — none other than Ferris, the Golden Record's original producer — about the project, and Ferris gave his blessing, with one important caveat.

Voyagers' Records Wait for Alien Ears

"You can't release a record without remastering it," says Ferris. "And you can't remaster without locating the master."

That turned out to be a taller order than expected. The original records were mastered in a CBS studio, which was later acquired by Sony — and the master tapes had descended into Sony's vaults.

Pescovitz enlisted the company's help in searching for the master tapes; in the meantime, he and Daly got to work acquiring the rights for the music and photographs that comprised the original. They also reached out to surviving musicians whose work had been featured on the record to update incomplete track information.

Finally, Pescovitz and Daly got word that one of Sony's archivists had found the master tapes.

Pescovitz remembers the moment he, Daly and Ferris traveled to Sony's Battery Studios in New York City to hear the tapes for the first time.

"They hit play, and the sounds of the Solomon Islands pan pipes and Bach and Chuck Berry and the blues washed over us," Pescovitz says. "It was a very moving and sublime experience."

Daly says that, in remastering the album, the team decided not to clean up the analog artifacts that had made their way onto the original master tapes, in order to preserve the record's authenticity down to its imperfections.

"We wanted it to be a true representation of what went up," Daly says.

Pescovitz and Daly teamed up with Lawrence Azerrad, a graphic designer who has made record packaging for the likes of Sting and Wilco , to design a luxuriant box set, complete with a coffee table book of photographs and, of course, tinted vinyl.

"I mean, if you do a golden record box set, you have to do it on gold vinyl," Daly says.

They put the project on Kickstarter and expected to sell it mostly to vinyl collectors, space nerds and audiophiles — but they underestimated the appeal.

"The internet was just on fire, talking about this thing," Daly says.

They blew past their initial funding goal in two days, eventually raising more than $1.3 million dollars, making it the most successful musical Kickstarter campaign ever. Among the initial 11,000 contributors were family members of NASA's original Voyager mission team.

An Alien View Of Earth

Last week, Ferris got his box set in the mail. He says that his friend, the late Carl Sagan, would be delighted by what they made.

"I think this record exceeds Carl's — not only his expectations, but probably his highest hopes for a release of the Voyager record," Ferris says. "I'm glad these folks were finally able to make it happen."

Pescovitz says he's just glad to have returned the Golden Record to the world that created it.

At a moment of political division and media oversaturation, Pescovitz and Daly say they hope that their Golden Record can offer a chance for people to slow down for a moment; to gather around the turntable and bask in the crackly sounds of what Sagan called the "pale blue dot" that we call home.

"As much as it was a gift from humanity to the cosmos, it was really a gift to humanity as well," Pescovitz says. "It's a reminder of what we can accomplish when we're at our best."

Link to Smithsonian homepage

Voyager Golden Record: Through Struggle to the Stars

Voyager "Sounds Of Earth" Record Cover, 1977, National Air and Space Museum, Transferred from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

An intergalactic message in a bottle, the Voyager Golden Record was launched into space late in the summer of 1977. Conceived as a sort of advance promo disc advertising planet Earth and its inhabitants, it was affixed to Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, spacecraft designed to fly to the outer reaches of the solar system and beyond, providing data and documentation of Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto. And just in case an alien lifeform stumbled upon either of the spacecraft, the Golden Record would provide them with information about Earth and its inhabitants, alongside media meant to encourage curiosity and contact.

Listen to the music recorded on the Voyager album with this Spotify playlist from user Ulysses' Classical.

Recorded at 16 ⅔ RPM to maximize play time, each gold-plaited, copper disc was engraved with the same program of 31 musical tracks—ranging from an excerpt of Mozart’s Magic Flute to a field recording made by Alan Lomax of Solomon Island panpipe players—spoken greetings in 55 languages, a sonic collage of recorded natural sounds and human-made sounds (“The Sounds of Earth”), 115 analogue-encoded images including a pulsar map to help in finding one’s way to Earth, a recording of the creative director’s brainwaves, and a Morse-code rendering of the Latin phrase per aspera ad astra (“through struggle to the stars”). In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first Earth craft to burst the heliospheric bubble and cross over into interstellar space. And in 2018, Voyager 2 crossed the same threshold.

A tiny speck of a spacecraft cast into the endless sea of outer space, each Voyager craft was designed to drift forever with no set point of arrival. Likewise, the Golden Record was designed to be playable for up to a billion years, despite the long odds that anyone or anything would ever discover and “listen” to it. Much like the Voyager spacecraft themselves, the journey itself was in large part the point—except that instead of capturing scientific data along the way, the Golden Record instead revealed a great deal about its makers and their historico-cultural context.

In The Vinyl Frontier: The Story of the Voyager Golden Record (2019), a book published by Bloomsbury’s Sigma science imprint, author Jonathan Scott captures both the monumental scope of the Voyager mission, relentless as space itself, and the very human dimensions of the Gold Record discs: “When we are all dust, when the Sun dies, these two golden analogue discs, with their handy accompanying stylus and instructions, will still be speeding off further into the cosmos. And alongside their music, photographs and data, the discs will still have etched into their fabric the sound of one woman’s brainwaves—a recording made on 3 June 1977, just weeks before launch. The sound of a human being in love with another human being.”

From sci-fi literature to outer-space superhero fantasies, from Afrofuturism to cosmic jazz to space rock, space-themed artistic expressions often focus on deeply human narratives such as love stories or stories of war. There seems to be something about traveling into outer space, or merely imagining doing so, that bring out many people’s otherwise-obscured humanity—which may help explain all the deadly serious discussions over the most fantastical elements of Star Trek and Star Wars , or Sun Ra and Lady Gaga. In the musical realm, space-based music frequently aims for the most extreme states of human emotion whether body-based or mind-expanding, euphoric or despairing. In other words, these cosmic art forms are pretty much expected to test boundaries and cross thresholds, or at least to make the attempt. The Voyager Golden Record was no exception.

The “executive producer” behind the Golden Record was the world-famous astrophysicist, humanist, and champion of science for the everyman, Carl Sagan (1934–1996). Equally a pragmatist and a populist, he was the perfect individual to oversee the Golden Record with its dual utilitarian and utopian aims. In his 1973 book The Cosmic Connection: An Extraterrestrial Perspective , Sagan writes that humans have long “wondered whether they are in some sense connected with the awesome and immense cosmos in which the Earth is imbedded,” touching again on the meeting point between everyday mundane realities and “escapist” fantasies, a collision that animates a great deal of science fiction and cosmic-based music. In his personal notes from the time of The Cosmic Connection , Sagan makes reference to music as “a means of interstellar communication.” So how would he utilize music to create these moments of connection and convergence?

It’s little wonder that Sagan endorsed the inclusion of a record on spaceships, with music specially selected to call out to the outer reaches of space. Music was a “universal language” in his telling due to its “mathematical” form, decipherable to any species with a capacity for advanced memory retention and pattern recognition. But this universal quality didn’t stop it from expressing crucial aspects of what earthlings were and what makes us tick, or the many different types of individuals and cultures at work on the planet Earth. Moving beyond the strict utility of mathematics, he also believed that music could communicate the uniquely emotional dimensions of human existence. Whereas previous visual-based messages shot into space “might have encapsulated how we think, this would be the first to communicate something of how we feel” (Scott 2019).

Further refining this idea, Jon Lomberg, a Golden Record team member who illustrated a number of Carl Sagan’s books, argued for an emphasis on “ideal” types of music for the interstellar disc: “The [Golden] Record should be more than a random sampling of Earth’s Greatest Hits...We should choose those forms which are to some degree self-explanatory forms whose rules of structure are evident from even a single example of the form (like fugues and canons, rondos and rounds).”

Ethnomusicologists Alan Lomax and Robert E. Brown were brought in as collaborators, offering their expertise in the world’s music and knowledge of potential recordings to be used. The latter’s first musical recommendation to Sagan hewed to the stated ideal of music which establishes its own structural rules from the get-go—and by association, how these rules may be broken—all overlaid by the yearning of the singer’s voice and the longing expressed in the lyrics. As he described it in his program notes written for Sagan: ‘“Indian vocal music’ by Kesarbai Kerkar…three minutes and 25 seconds long…a solo voice with a seven-tone modal melody with auxiliary pitches [and] a cyclic meter of 14 beats, alongside drone, ‘ornamentation’ and drum accompaniment and some improvisation.” He also gives a partial translation to the words of the music: “Where are you going? Don’t go alone…”

Taken as a whole, the Voyager Golden Record is reminiscent of a mixtape made by an eccentric friend with an encyclopedic knowledge of the world’s music—leaping from track-to-track, across continents and historical periods, crossing heedlessly over the dividing lines drawn between art, folk, and popular musics, but with each track a work of self-contained precision and concision. The disc plays out as a precariously balanced suite of global musical miniatures, a mix where it’s perfectly plausible for Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode” to end up sandwiched between a mariachi band and a field recording of Papua New Guinean music recorded by a medical doctor from Australia. Human diversity is the byword, diversity as a trait of humanity itself. The more the individual tracks stand in relief to one another the better.

Given all of this, one could make a plausible case that the Voyager Golden Record helped “invent” a new approach of world music, one where musical crosstalk isn’t subtle or peripheral, but where it’s more like the center pole of musical creation itself. While it’s hardly clear if Sagan or most of his other collaborators had this goal in mind, creative director Ann Druyan certainly did. Or at least she did when it came to her insistence on including Chuck Berry on the Golden Record. As she puts it in a 60 Minutes interview from 2018, “ Johnny B. Goode , rock and roll, was the music of motion, of moving, getting to someplace you've never been before, and the odds are against you, but you want to go. That was Voyager." And so rock ‘n’ roll is turned into true “world music.”

Whether by chance or by design, the Voyager Golden Record anticipated the shifting cultural and aesthetic contexts through which many listeners heard and understood “world music,” a shift that would become blatantly obvious in the decades to come. More than a culturally-sensitive replacement for labels like “exotic music” and “primitive music,” more than a grab bag of unclaimed non-Western musics and vernacular musics, the Golden Record anticipated a sensibility in which the “world” in world music was made more literal—both by fusion-minded musicians, and by music retailers who placed these fusions in newly-designated “world music” sections. (but one must acknowledge that these musical fusions were sometimes problematic in their own right, too often relying on power differentials between borrower and borrowed-from music and musicians)

In this respect, and in other respects beyond our scope here, "world music" embodied many of the contradictions inherent to the rise of globalization, postmodernism, hyperreality, neoliberalism, etc.—coinciding with the crossing of a threshold sometime in the 1970s or ‘80s according to most accounts—with the outcome being a world that’s ever more integrated (the global economy, the global media, global climate change) but also ever more polarized, each dynamic inextricably linked to its polar opposite—a sort of interstellar zone where the normal laws of physics no longer seem to apply.

By taking diversity and juxtaposition as aesthetic ideals rather than drawbacks, the creators of the Voyager Golden Record sketched a sonic portrait of the planet Earth and, at the same time, anticipating the art of the mixtape, yet another trend that would come to fruition in the 1980s. Not unlike a mixtape made for a new friend or a prospective love interest, the Golden Record was designed both to impress —an invitation for aliens to travel across the universe just to meet us—and to express who we are as a people and as a planet.

With the Golden Record as a mixtape-anticipating bid for cosmic connection, it’s fitting that its creative spark was lit in large part by the love affair that developed between Carl Sagan and Ann Druyan in the summer of 1977. To the self-professed surprise of both, they became engaged in the middle of an impulsive phone call and conversation, before they had even officially moved beyond friendship. They remained happily married until Carl Sagan passed away in 1996. On a National Public Radio segment broadcast in 2010, Ann Druyan described the moments leading up to that pivotal phone call and its lifelong aftermath—a relationship made official across space and over a wire—“It was this great eureka moment. It was like scientific discovery.” Several days later, Druyan’s brainwaves were recorded to be included on the Golden Record —her own idea—while she thought about their eternal love.

Given the sudden and unexpected manner in which they fell in love and into sync, it maybe didn’t seem too crazy to believe that infatuation could beset some lonely extraterrestrial who discovered their Golden Record too, especially if this unknown entity plugged into Druyan’s love waves. After all, the Voyager mission itself was planned around a cosmic convergence that only takes place once in the span of several lifetimes. Much like the star-crossed lovers, the stars had to literally align for the mission to be possible at all. The Voyager mission took advantage of a rare formation of the solar system’s most distant four planets that made the trip vastly faster and more feasible, using the gravitational pull of one planet as an “onboard propulsion system” to hurl itself toward the nest destination. With all the jigsaw puzzle pieces so perfectly aligned for the first part of the mission, it would be a shame if some mixtape-loving alien never came for a visit. The main question being if anyone will be here to meet them by the time they get here. As Jimmy Carter put it in his written message attached to the Golden Record:

This is a present from a small, distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts and our feelings. We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours.

Dallas Taylor, host of independent podcast Twenty Thousand Hertz, explores the Voyager album track-by-track in episode 65: "Voyager Golden Record." Visit the podcast website to listen.

Written and compiled by Jason Lee Oakes, Editor, Répertoire International de Littérature Musicale (RILM)

This post was produced through a partnership between Smithsonian Year of Music and RILM .

Bibliography

DiGenti, Brian. “Voyager Interstellar Record: 60 Trillion Feet High and Rising.” Wax Poetics 55 (Summer 2013): 96. In the summer of 1977, just after Kraftwerk dropped Trans-Europe Express , Giorgio Moroder offered the world the perfect marriage of German techno with American disco in Donna Summer's "I feel love," the first dance hit produced wholly by synthesizer and the precursor to the underground dance movement. Meanwhile, there was another gold record in the works. The Voyager Interstellar Message Project, a NASA initiative led by astronomer Carl Sagan and creative director Ann Druyan, was a chance at communicating with any intelligent life in outer space. In an unintended centennial celebration of the phonograph, the team created a gold-plated record that would be attached to the Voyager 1 and 2 probes—the Voyager Golden Record—a time capsule to express the wonders of planet Earth in sound and vision. As they were tasked with choosing images and music for this 16-2/3 RPM "cultural Noah's Ark"—a little Mozart, some Chuck Berry, Louis Armstrong, and Blind Willie Johnson—the pair of geniuses fell madly for each other, vowing to marry within their first moments together. Their final touch was to embed Ann's EEG patterns into the record as an example of human brain waves on this thing called love. (author)

Meredith, William. “The Cavatina in Space.” The Beethoven Newsletter 1, no. 2 (Summer 1986): 29–30. When the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration launched its spacecraft Voyager I and II in 1977, each carried a gold-plated copper record intended to serve as a communication to "possible extraterrestrial civilizations.” Each record contains photographs of earth, "the world's greatest music," an introductory audio essay, and greetings to extraterrestrials in 60 languages. Two of the record's eight examples of art music are by Beethoven (the first movement of the symphony no. 5 and the cavatina of the string quartet in B-flat major, op. 130). The symphony no. 5 was selected because of its "compelling" and passionate nature, new physiognomy, innovations, symmetry, and brevity. The cavatina was chosen because of its ambiguous nature, mixing sadness, hope, and serenity. (author)

Sagan, Carl. Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record . New York: Random House, 1978. On 20 August and 5 September 1977, two extraordinary spacecraft called Voyager were launched to the stars (Voyager 1 and Voyager 2). After what promises to be a detailed and thoroughly dramatic exploration of the outer solar system from Jupiter to Uranus between 1979 and 1986, these space vehicles will slowly leave the solar systems—emissaries of the Earth to the realm of the stars. Affixed to each Voyager craft is a gold-coated copper phonograph record as a message to possible extra-terrestrial civilizations that might encounter the spacecraft in some distant space and time. Each record contains 118 photographs of our planet, ourselves, and our civilization; almost 90 minutes of the world's greatest music; an evolutionary audio essay on "The Sounds of Earth"; and greetings in almost 60 human languages (and one whale language), including salutations from the President Jimmy Carter and the Secretary General of the United Nations. This book is an account, written by those chiefly responsible for the contents of the Voyager Record, of why we did it, how we selected the repertoire, and precisely what the record contains.

Scott, Jonathan. The Vinyl Frontier: The Story of the Voyager Golden Record . London: Bloomsbury Sigma, 2019. In 1977, a team led by the great Carl Sagan was put together to create a record that would travel to the stars on the back of NASA's Voyager probe. They were responsible for creating a playlist of music, sounds and pictures that would represent not just humanity, but would also paint a picture of Earth for any future alien races that may come into contact with the probe. The Vinyl Frontier tells the whole story of how the record was created, from when NASA first proposed the idea to Carl to when they were finally able watch the Golden Record rocket off into space on Voyager. The final playlist contains music written and performed by well-known names such as Bach, Beethoven, Glenn Gould, Chuck Berry and Blind Willie Johnson, as well as music from China, India and more remote cultures such as a community in Small Malaita in the Solomon Islands. It also contained a message of peace from US president Jimmy Carter, a variety of scientific figures and dimensions, and instructions on how to use it for a variety of alien lifeforms. Each song, sound and picture that made the final cut onto the record has a story to tell. Through interviews with all of the key players involved with the record, this book pieces together the whole story of the Golden Record. It addresses the myth that the Beatles were left off of the record because of copyright reasons and will include new information about US president Jimmy Carter's role in the record, as well as many other fascinating insights that have never been reported before. It also tells the love story between Carl Sagan and the project's creative director Ann Druyan that flourishes as the record is being created. The Golden Record is more than just a time capsule. It is a unique combination of science and art, and a testament to the genius of its driving force, the great polymath Carl Sagan. (publisher)

Smith, Brad. “Blind Willie Johnson’s ‘Dark was the Night, Cold was the Ground’.” The Bulletin of the Society for American Music 41, no. 2 (Spring 2015): [9]. Blind Willie Johnson's 1927 recording of “ Dark was the Night, Cold was the Ground ” was included on the copper record that accompanied Voyager I and II into space, placed just before the cavatina of Beethoven's string quartet op. 130. The author searches for the reasons the NASA team considered it among the world's greatest music, relating Johnson's interpretation to the hymn text of the same title written by Thomas Haweis and published in 1792, and analyzing Johnson's slide guitar technique and vocal melismas. Johnson's rhythmic style, with its irregularities, is discussed with reference to Primitive Baptist singing style. (journal)

Katibim Records + 15 [A Time Machine For Only 1h] (Final Episode) The Lake Radio

"A Time Machine For Only 1h" "Katibim Records" is a mixtape project launched by Istanbul-based music critic Özgün Çağlar in 2022. Inspired by the Voyager Golden Records, Katibim Records is a collection of modern and folk songs from communities around the world, mixing avant-garde, psychedelic, and the old-fashioned mainstream. It has been broadcast on different radio stations in Turkey. Specially produced for The Lake radio listeners, "Katibim Records +" is on air every two weeks. An inter-temporal and inter-genre 'voyage' from former Soviet territories to Latin America, the Levant and Asia. A chance to listen before the aliens! Tracklist: 01. Branko Mataja - Da Smo Se Ranije Sreli (1974, Yugoslavia) 02. eden ahbez - Myna Bird (1960, US) 03. سلوى / Salwa - Choufi Khalfel Bahr (1977, Lebanon) 04. Art Blakey & The Afro-Drum Ensemble - Love, The Mystery Of (1962, US) 05. Rabih Abou-Khalil - Blue Camel (1992, Germany) 06. Ali Hassan Kuban - Sukkar, Sukkar, Sukkar (1989, Germany) 07. Shankar Jaikishan & Rais Khan - Raga: Malkauns (1968, India) 08. Biricik - Ben O Zaman Ölürüm (1975, Turkey) 09. Cengiz Coşkuner - Konyalı (1973, Turkey) 10. Κώστας Σούκας / Kostas Soukas - Τσιφτετέλι Του Σούκα (1979, Greece) 11. מישל / Michel (Cohen) - לא הבטחתי לך דבר (1981, Israel) 12. Cantekin - Fırtınadır Eser Gönül (1974, Turkey) 13. Ատիս Հարմանտեան / Adiss Harmandyan - Amen Aravod (1973, Lebanon) 14. Sargon (H.) Gabriel - Neshret Attour (1973, US) 15. Vijay Benedict - Jeyona Aamaye Chede (1988, India) @musikiheyeti

- Episode Website

- More Episodes

- All rights reserved

Top Podcasts In Music

Are we deceiving aliens about the reality of life on this planet? Or just ourselves?

The golden record on voyager 1 brings a curiously optimistic collection of sounds and images for potential discovery by non-earthlings.

The Gold Record on Voyager 1: Where is the crunch of rubble as parents search for the hand of a missing child? Where are the cries of grief and desperation from war zones? Photograph: Space Frontiers/Archive Photos/Getty

In 1977, Voyager 1 and 2 spacecrafts began their mission. Thirty-five years later, Voyager 1 would make history by becoming the first human-made object to enter interstellar space.

Summer of Family: This summer, parents are looking for tips, advice and information on how to help their children thrive during the holiday months. You can read all about it at irishtimes.com/health/your-family

After a brief computer issue arose late last year, Voyager 1 has recently resumed returning data to scientists waiting patiently at a 22½-hour delay on Earth. Not bad, considering that it was with a 46-year delay that news of the mission reached this writer.

The spacecrafts were launched by the Titan-Centaur rocket with the purpose of exploring the planets Jupiter and Saturn. However, for someone whose brain latches to stories, there was a more compelling element to this quest.

Aboard the spacecraft, now more than 15 billion miles from Earth, in what is known as “empty space”, is a 12-inch gold-plated disc. This “Golden Record” is a cosmic time capsule that contains a selection of images, music, greetings and natural sounds.

Taylor Swift in Dublin: Ticket information, setlist, stage times and more

:quality(70):focal(2090x810:2100x820)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/4UGER4OCPJDVDF5TBU2US7WQGQ.jpg)

‘I am working with a very difficult person and it is having a huge effect on my life’

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/O3DB7EAOTZGWZJ23QZSKRSH34M.jpg)

In pictures: Summer solstice celebrations at the Hill of Tara

:quality(70)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/EWDBOZ2FHRD77B2HIAILYXVBJQ.JPG)

Harbour Kitchen review: This is a cracking coastal restaurant

:quality(70):focal(5565x2435:5575x2445)/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/irishtimes/RB6SPMWPO5EPPGIRMJDCHS664Q.JPG)

[ Voyager 1 space probe transmits data again after remote Nasa fix from 24bn kilometres away ]

According to Nasa , the aim of the record is to “communicate a story of our world to extra-terrestrials”. A tall order. How do you create a single object that says with confidence to a foreign civilisation that, “this is who we are”?

The Golden Record is electroplated in an ultra-pure source of uranium-238. The half-life of this substance is 4.51 billion years. This means that the record may potentially outlive humankind. Serving as an artefact of what human civilisation once was.

Oof, gut-tightening stuff.

The contents of the record were selected for Nasa by a committee chaired by American astronomer Carl Sagan. Accompanying the Golden Record are instructions, mapped out in a symbolic language on how to use the disc. It also includes co-ordinates for planet Earth, should an alien civilisation want to make contact. And why wouldn’t they with the glorious depiction of life on Earth that we have sent their way?

[ Nasa restores contact with Voyager 2 spacecraft after mistake led to silence ]

The disc contains 115 images that are encoded in analogue form. The images represent a diversity of life on Earth, varying from mathematical equations to traffic jams, astronauts floating through space, to a teacher bent over his student. There are images of X-rays, idyllic turquoise sea, a cotton harvest, and diagrams of a foetus and human reproductive systems. After some contention, it was decided that no nudes would be sent to space.

These images are accompanied by a “sound essay” made up of the greetings, music and a selection of “Earth sounds”. The musical selection includes classical music, jazz, a Peruvian wedding song and a Native American “night chant”. Contrary to popular belief, The Beatles’ Here Comes the Sun does not feature.

The Earth sounds include volcanoes, thunderstorms and bubbling mud; the trilling of crickets and the howl of wolves. We hear hyenas and heartbeats, laughter and the pucker of a kiss. There are sounds of fire, Morse code and a mother attending to her upset child.

The greetings come in 55 languages, beginning with Akkadian, which was spoken in Sumer about six thousand years ago, and ending with Wu, a modern Chinese dialect.

They also include a printed message from former UN secretary general Kurt Waldheim that states:

“I send greetings on behalf of the people of our planet. We step out of our Solar System into the Universe, seeking only peace and friendship, to teach if we are called upon, to be taught if we are fortunate. We know full well that our planet and all its inhabitants are but a small part of this immense Universe that surrounds us, and it is with humility and hope that we take this step.”

[ The Precipice - Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity: a thesis of sweeping optimism ]

While a message from China touchingly asks their “friends of space” if they have eaten.

Sagan notes that the record will be “played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilisations in interstellar space. But the launching of this bottle into the cosmic ocean says something very hopeful about life on this planet.”

Indeed, the record does present a hopeful view of life on Earth. But I wonder if Sagan was alive today, how the astronomer and his team might reflect on their choices. I wonder if, like me, they might worry about the extra-terrestrial creatures who, upon digesting the golden disc, may choose to visit this utopia, only to arrive and witness the aspects we had chosen to leave out about life here.

Where are the death rattles, the clunk of amputated limbs or the sound of an infant sucking a dry breast?

Where is the crunch of rubble as parents search for the hand of a missing child?

The cries of grief and desperation or the squeak of a sharpie pen signing a message onto another bomb intended to kill?

Where is the deafening silence or the hollow sound of inaction?

What lovely messages we have sent to space, but are we deceiving extra-terrestrial beings about the reality of life on this planet?

Or perhaps are we simply just deceiving ourselves?

IN THIS SECTION

Surviving suicidality: ‘running gave me my life, so i will give my life to running’, gary lineker’s ‘bald patch’ jibe hurt frank lampard - luckily, there is one treatment for hair loss, families: the untapped superpower in eating disorder recovery, taylor swift fans caught up in aer lingus strike: ‘i’m disappointed. if it stays the same, i will be selling my ticket’, nine music festivals cancelled this year, more affected next year without state intervention, dáil hears, aer lingus passengers face more flight cancellations as talks break down, natasha o’brien says she is willing to meet with mcentee to discuss violence in ireland, biden v trump presidential debate: where to watch and what to expect, uncontrolled asylum acting as a cover for economic migration needs a more radical response, martyn turner, latest stories, universities say they face shortage of funds to pay existing staff this year, mover mortgage approvals decline in may amid shortage of second-hand homes, eu leaders agree to support ursula von der leyen for second term, douglas is cancelled review: downfall of a cuddly, national uk treasure is no laughing matter.

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Information

- Cookie Settings

- Community Standards

Spotify is currently not available in your country.

Follow us online to find out when we launch., spotify gives you instant access to millions of songs – from old favorites to the latest hits. just hit play to stream anything you like..

Listen everywhere

Spotify works on your computer, mobile, tablet and TV.

Unlimited, ad-free music

No ads. No interruptions. Just music.

Download music & listen offline

Keep playing, even when you don't have a connection.

Premium sounds better

Get ready for incredible sound quality.

- The Contents

- The Making of

- Where Are They Now

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Q & A with Ed Stone

golden record

Where are they now.

- frequently asked questions

- Q&A with Ed Stone

The Golden Record Cover

In the upper left-hand corner is an easily recognized drawing of the phonograph record and the stylus carried with it. The stylus is in the correct position to play the record from the beginning. Written around it in binary arithmetic is the correct time of one rotation of the record, 3.6 seconds, expressed in time units of 0,70 billionths of a second, the time period associated with a fundamental transition of the hydrogen atom. The drawing indicates that the record should be played from the outside in. Below this drawing is a side view of the record and stylus, with a binary number giving the time to play one side of the record - about an hour.

The information in the upper right-hand portion of the cover is designed to show how pictures are to be constructed from the recorded signals. The top drawing shows the typical signal that occurs at the start of a picture. The picture is made from this signal, which traces the picture as a series of vertical lines, similar to ordinary television (in which the picture is a series of horizontal lines). Picture lines 1, 2 and 3 are noted in binary numbers, and the duration of one of the "picture lines," about 8 milliseconds, is noted. The drawing immediately below shows how these lines are to be drawn vertically, with staggered "interlace" to give the correct picture rendition. Immediately below this is a drawing of an entire picture raster, showing that there are 512 vertical lines in a complete picture. Immediately below this is a replica of the first picture on the record to permit the recipients to verify that they are decoding the signals correctly. A circle was used in this picture to ensure that the recipients use the correct ratio of horizontal to vertical height in picture reconstruction.

The drawing in the lower left-hand corner of the cover is the pulsar map previously sent as part of the plaques on Pioneers 10 and 11. It shows the location of the solar system with respect to 14 pulsars, whose precise periods are given. The drawing containing two circles in the lower right-hand corner is a drawing of the hydrogen atom in its two lowest states, with a connecting line and digit 1 to indicate that the time interval associated with the transition from one state to the other is to be used as the fundamental time scale, both for the time given on the cover and in the decoded pictures.

Electroplated onto the record's cover is an ultra-pure source of uranium-238 with a radioactivity of about 0.00026 microcuries. The steady decay of the uranium source into its daughter isotopes makes it a kind of radioactive clock. Half of the uranium-238 will decay in 4.51 billion years. Thus, by examining this two-centimeter diameter area on the record plate and measuring the amount of daughter elements to the remaining uranium-238, an extraterrestrial recipient of the Voyager spacecraft could calculate the time elapsed since a spot of uranium was placed aboard the spacecraft. This should be a check on the epoch of launch, which is also described by the pulsar map on the record cover.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The following music was included on the Voyager record. Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F. First Movement, Munich Bach Orchestra, Karl Richter, conductor. 4:40; Java, court gamelan, "Kinds of Flowers," recorded by Robert Brown. 4:43; Senegal, percussion, recorded by Charles Duvelle. 2:08

The remainder of the record is in audio, designed to be played at 16-2/3 revolutions per minute. It contains the spoken greetings, beginning with Akkadian, which was spoken in Sumer about six thousand years ago, and ending with Wu, a modern Chinese dialect.Following the section on the sounds of Earth, there is an eclectic 90-minute selection of music, including both Eastern and Western ...

The Voyager Golden Record contains 116 images and a variety of sounds. The items for the record, which is carried on both the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft, were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University.Included are natural sounds (including some made by animals), musical selections from different cultures and eras, spoken greetings in 59 languages ...

The Voyager Golden Records are two identical phonograph records which were included aboard the two Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977. ... This is a present from a small, distant world, a token of our sounds, our science, our images, our music, our thoughts and our feelings. We are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours.

Sounds of Earth The following is a listing of sounds electronically placed onboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. Music from Earth The following music was included on the Voyager record. Country of origin Composition Artist(s) Length Germany Bach, Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F. First Movement Munich Bach Orchestra, Karl Richter, conductor 4:40 Java […]

The remainder of the record is in audio, designed to be played at 16-2/3 revolutions per minute. It contains the spoken greetings, beginning with Akkadian, which was spoken in Sumer about six thousand years ago, and ending with Wu, a modern Chinese dialect.Following the section on the sounds of Earth, there is an eclectic 90-minute selection of music, including both Eastern and Western ...

Murmurs of Earth - these recordings are floating out in space on the Voyager I & 2 Satellites. Thanks to giulianobevisangue for posting most of these. "Pygmy...

The following is a listing of sounds electronically placed onboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. Music of The Spheres; Volcanoes, Earthquake, Thunder; Mud Pots; Wind, Rain, Surf; Crickets, Frogs; ... golden record Overview; The Cover; The Contents; The Making of; Galleries. Videos;

This playlist contains the greeting from the UN Secretary General, greetings in 55 languages, UN greetings with whale sounds, earth sounds, and music tracks ...

Voyage - Songs from the Voyager Golden Record. Playlist • m1lkm4n • 2020. 2.2M views • 27 tracks • 1 hour, 36 minutes Murmurs of Earth - these recordings are floating out in space on the Voyager I & 2 Satellites. Thanks to giulianobevisangue for posting most of these. "Pygmy girls' initiation song" from Zaire was the only track I could ...

I organized this list in track order. Musics in Voyager's Golden Record are total 27 songs. But as you noticed, this list made of 28 songs, because of 'The w...

Arguably one of human kind's most significant audio/music compilations, often referred to as earth's mixtape, is the Voyager Golden Record.. These phonograph records, constructed by Carl Sagan ...

April 22, 2012. The Golden Record consists of 115 analog-encoded photographs, greetings in 55 languages, a 12-minute montage of sounds on Earth and 90 minutes of music. J Marshall - Tribaleye ...

7. A Bulgarian Folk Song. The Voyager committee wanted the record's music to represent a wide range of eras and cultures. One track, titled "Izlel je Delyo Hagdutin," is a traditional folk song ...

Inspired by Lennon's trick of etching messages onto records, Ferris hand-etched an inscription on the Golden Record that reads, "To the makers of music — all worlds, all times." The team completed the selection process in time for NASA's launch of the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft at the end of summer 1977.

"The Voyager records are the farthest flung objects that humans have ever created," says Timothy Ferris, a veteran science and music journalist and the producer of the Golden Record.

Voyager Golden Record · Playlist · 28 songs · 22.9K likes. Voyager Golden Record · Playlist · 28 songs · 22.9K likes. Voyager Golden Record · Playlist · 28 songs · 22.9K likes. Voyager Golden Record · Playlist · 28 songs · 22.9K likes. Home; Search; Your Library. Playlists Podcasts & Shows Artists Albums ...

The Golden Record. Pioneers 10 and 11, which preceded Voyager, both carried small metal plaques identifying their time and place of origin for the benefit of any other spacefarers that might find them in the distant future. With this example before them, NASA placed a more ambitious message aboard Voyager 1 and 2, a kind of time capsule ...

An intergalactic message in a bottle, the Voyager Golden Record was launched into space late in the summer of 1977. Conceived as a sort of advance promo disc advertising planet Earth and its inhabitants, it was affixed to Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, spacecraft designed to fly to the outer reaches of the solar system and beyond, providing data and documentation of Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto.

This is the music colletion on Voyager Record which was selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University

Voyager Golden Record. In 1977, Carl Sagan and other researchers collected sounds and images from planet Earth to send on Voyager 1 and Voyager 2. The Voyager Golden Record includes recordings of frogs, crickets, volcanoes, a human heartbeat, laughter, greetings in 55 languages, and 27 pieces of music. "Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground ...

"A Time Machine For Only 1h" "Katibim Records" is a mixtape project launched by Istanbul-based music critic Özgün Çağlar in 2022. Inspired by the Voyager Golden Records, Katibim Records is a collection of modern and folk songs from communities around the world, mixing avant-garde, psychedelic, and…

The Golden Record on Voyager 1 brings a curiously optimistic collection of sounds and images for potential discovery by non-Earthlings

The following is a listing of pictures electronically placed on the phonograph records which are carried onboard the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. The contents of the record were selected for NASA by a committee chaired by Carl Sagan of Cornell University, et. al. Dr. Sagan and his associates assembled 115 images and a variety of natural sounds ...

Listen to this episode from My Blog » Bianca Poole on Spotify. Download EPub Alien Listening: Voyager's Golden Record and Music from Earth by Daniel K. L. Chua on Ipad Full Volumes Read EPub Alien Listening: Voyager's Golden Record and Music from Earth by Daniel K. L. Chua is a great book to read and thats why I recommend reading or downloading ebook Alien Listening: Voyager's Golden ...

Electroplated onto the record's cover is an ultra-pure source of uranium-238 with a radioactivity of about 0.00026 microcuries. The steady decay of the uranium source into its daughter isotopes makes it a kind of radioactive clock. Half of the uranium-238 will decay in 4.51 billion years. Thus, by examining this two-centimeter diameter area on ...