Leiper’s Tourism System: A simple explanation

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Leiper’s Tourism System is a basic conceptualisation of the structure of the tourism industry . It is one of the most widely accepted and most well-known models used in tourism research when attempting to understand the tourism system.

Many tourism students will learn about Leiper’s Tourism System towards the beginning of their studies alongside the history of tourism and the importance of tourism . Many people working within the industry learn about Leiper’s Tourism System in order to underpin and inform their operational plans.

But what is Leiper’s Tourism System? In this article I will tell you about who Leiper was, why he was a credible scholar (and why people listen(ed) to him) and how his Tourism System model works in the context of tourism management.

Who was Leiper?

Why was leiper’s tourism system developed, leiper’s tourism system – how does it work, the tourists, the geographical features, the tourism industry, the traveller generating region, the tourist destination region, the tourist transit region, the benefits of leiper’s tourism system, the disadvantages of leiper’s tourism system, to conclude, further reading.

Neil Leiper was an Australian tourism scholar who died in February 2010. His work was extremely influential and continues to be well cited throughout the tourism literature.

Leiper has four major areas in which he focussed his research: tourism systems, partial industrialisation, tourist attraction systems and strategy. It is his work on tourism systems that I will discuss in this post.

Leiper’s research was identified as having a significant influence on travel and tourism academic literature, as well as the conceptualisation of tourism as a discipline. This applies to both research and educational contexts.

Leiper was famed for the connections that he made between theory and strategy, which helped to bridge the gap between theory, policy and practice.

You can read more about Neil Leiper and his academic contributions in this paper .

Discussions about what tourism is and how tourism is defined have been ongoing for many years.

Leiper’s contribution to the debate was to adopt a systems approach towards understanding tourism.

Leiper (1979) defined tourism as:

‘…the system involving the discretionary travel and temporary stay of persons away from their usual place of residence for one or more nights, excepting tours made for the primary purpose of earning remuneration from points en route. The elements of the system are tourists , generating regions, transit routes, destination regions and a tourist industry. These five elements are arranged in spatial and functional connections. Having the characteristics of an open system, the organization of five elements operates within broader environments: physical, cultural, social, economic, political, technological with which it interacts.’

Rather than viewing each part of the tourism system as independent and separate, Leiper’s definition was intended to allow for the understanding of destinations, generating areas, transit zones, the environment and flows within the context of a wider tourism system.

In essence, therefore, Leiper’s Tourism System was developed to encourage people to view tourism as an interconnected system, and to make relevant assessments, decisions, developments etc based upon this notion.

So now that we understand who Neil Leiper was (and that he was a credible tourism scholar), lets take a deeper look at his Tourism System.

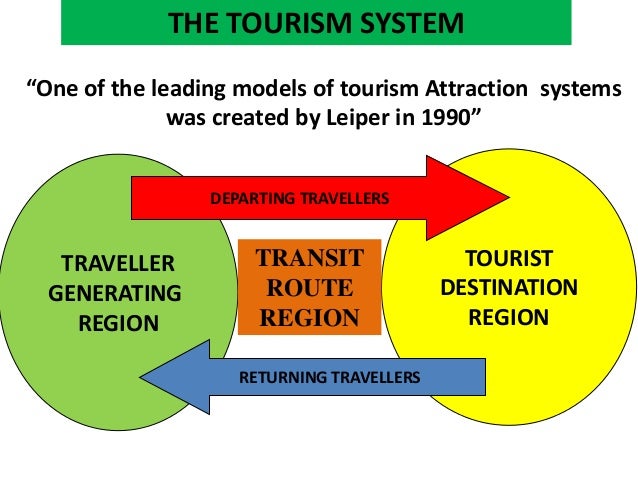

In the diagram above you can see the way in which Leiper depicted tourism as being a system.

Leiper did not want people to view each part of the tourism industry as being separate and independent, because it is not. Rather, each component of tourism is closely interrelated.

This means that each part of the system relies strongly upon other parts in order to function properly.

Lets take an unrelated example of a car engine. If one part of the engine isn’t working properly, the car won’t run efficiently or may not run at all…

Lets put this into the context of travel and tourism. If the airline isn’t running flights to a destination, then the hotel will have no business. And if there are no available hotels in the destination, then people will not book flights there.

Now, this is a very simplistic example, but hopefully that helps to provide a clearer picture of how the ‘tourism system’ is interconnected.

The basic elements of Leiper’s Tourism System

There are three major elements in Leiper’s Tourism System: the tourists, the geographical features and the tourism industry.

The tourist is the actor in Leiper’s tourism system. They move around the tourism system, consuming various elements along the way.

In Leiper’s tourism system he identifies three major geographical features: the traveller generating region, the tourist destination region and the tourist transit region.

I will explain which each of these geographical features means short.

The tourism industry is, of course, at the heart of the tourism system. All of the parts that make up the structure of tourism , are found within the tourism system.

The geographical features of Leiper’s Tourism System model

Leiper identifies three main geographical regions in his tourism system. These are visually depicted in the diagram above.

I will explain what each of the geographical features mean below.

Other posts that you may be interested in: – What is tourism? A definition of tourism – The importance of tourism – The history of tourism – Stakeholders in tourism – The structure of tourism – Types of tourism: A glossary

The traveller generating region is the destination in which the tourist comes from.

Exactly what this means, is not entirely clear. Does it mean the departure airport? The home country? The area of the world? The home town? Well in part, I think that this depends on the nature of the tourism that is taking place.

If, for example, a person is taking a domestic holiday , then their home town will almost certainly be classified as the ‘traveller generating region’.

However, when we travel further away, the precise details of our home locations become less important. For example, you may refer instead to the country or district in which you live. Or you may simply refer to the country.

For example, if I were to travel to Spain, I may refer to my traveller generating region as the United Kingdom.

Similarly, sometimes we refer to areas of the world. This is especially the case with travellers from Asia. Some countries in Asia (such as China ) are substantial tourist generating regions. Rightly or wrongly, however, the traveller destination region is often given the vague description of simply being ‘Asia’.

Within the traveller generating region there are many components of tourism.

Here you will often find stakeholders i n tourism such as travel agents and tour operators, who promote outbound or domestic tourism.

The tourist destination region can largely be described in the same vain.

In Leiper’s tourism system, the tourism destination region is the area that the tourist is visiting.

This could be a small area, such as a village or tourist resort. For example, Bentota in Sri Lanka or Dahab in Egypt.

The tourist destination region could be an entire province. For example, Washington State.

Likewise, it could be a country, such as Jordan . Or it could even be an area of the World, such as The Middle East.

In the tourist destination region you will find many components of tourism. Here you will likely find hotels, tourist attractions, tourist information centres etc.

The last geographical region identified in Leiper’s Tourism System is the tourist transit region.

The tourist transit region is the space between when the tourist leaves the traveller generating region and when they arrive at the tourist destination region. This is effectively the time that they are in transit.

The tourist transit region is largely made up of transport infrastructure. This could be by road, rail, air or sea. It involves a large number of transport operators as well as the organisations that work within them, such as catering establishments (think Burger King at the airport).

The tourist transit region is an integral part of Leiper’s Tourism System.

There are many benefits of Leiper’s tourism system.

Leiper’s model allows for a visual depiction of the tourism system. The model is relatively simple, enabling the many to comprehend and use this model.

Leiper’s Tourism System model has been widely cited within the academic literature and widely taught within tourism-based programmes at universities and colleges for many years.

The way in which this model demonstrates that the different parts of the tourism industry are interrelated and dependent upon each other provides scope for better planning and development of tourism .

There are, however, also some disadvantages to Leiper’s Tourism System model.

Whilst the simplicity of this model can be seen as advantageous, as it means that it can be understood by the many rather than the few, it can be argued that it is too simple.

Because the model is so simple, it is subject to interpretation, which could result in different people understanding it in different ways – I demonstrated when I discussed what ‘region’ meant.

Leiper developed this model back in 1979 and a lot has changed in travel and tourism since then. Take, for example, the use of the Internet.

Lets say that a person lives in Italy and books a trip to Thailand through an online travel agent who is based in the USA. Where in the model does the travel agent fit? Because they have little place in either the traveller generating region or the tourist destination region….

The post-modern tourism industry is not accounted for in this model, thus it can be argued that it is limited in scope because it is outdated.

Likewise, this model fails to address the way in which the tourism system is actually part of a network of interrelated systems. What about the agriculture sector? Or the construction industry? Or the media? All of these areas play an essential role in [feeding, building, promoting] tourism, but they are not represented in the model.

Leiper’s Tourism System is a key part of the foundation literature in travel and tourism.

It provides a good representation of the way that the many parts of the tourism industry work together as a system, rather than individually. However, it fails to account for many of the complexities of the industry and its ties with associated industries.

Nonetheless, this is an interesting model that is widely applicable both in an academic and practical sense.

If you would like to learn more about the fundamentals of the travel and tourism industry, I have listed some key texts below.

- An Introduction to Tourism : a comprehensive and authoritative introduction to all facets of tourism including: the history of tourism; factors influencing the tourism industry; tourism in developing countries; sustainable tourism; forecasting future trends.

- The Business of Tourism Management : an introduction to key aspects of tourism, and to the practice of managing a tourism business.

- Tourism Management: An Introduction : gives its reader a strong understanding of the dimensions of tourism, the industries of which it is comprised, the issues that affect its success, and the management of its impact on destination economies, environments and communities.

Liked this article? Click to share!

Tourism System

A system consists of several parts that are interconnected and interrelated, each part influencing each other through its dynamic nature while responding to the external influences as well. All the components within the system work to attain a common goal or purpose.

An influence in one part of the system will be felt throughout the system. It can be also referred to a spider’s web. Ludwig von Bertalanffy, a biologist has defined ‘ General system theory’ as a set of elements that experience interrelationship among themselves and with their external environments.

A system is an assemblage or interrelated combination of things or elements or components forming a unitary whole (Hall 2008). Tourism can be referred to as a system as it reacts to the external environments like the social, political, technological and ecological. Elements like attraction, transport, accommodation, facilities interact with each other while it interacts with the external environment too.

Concept of Tourism as a System

Tourism is conceptualized as a system by many scholars. It was in the 1970s that the General Systems Theory was applied to the concept of tourism and it has resulted in a number of system theories of tourism. Scholars like Leiper, Getz, Gunn and Mill and Morrison have suggested systems model for tourism. In his book, tourism planning

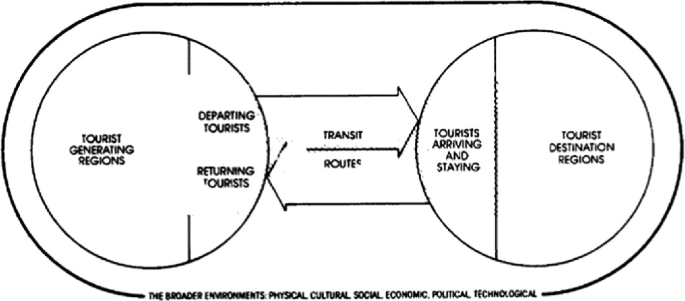

(1979), Gunn put forth the “tourism fundamental system” that involved five components: tourist, transportation, attractions, services-facilities, and information-direction. Leiper (1979) developed the whole tourism systems based on the systems theory and identified five basic components: tourists, generating regions, transit routes, destination regions, and a tourist industry operating within physical, cultural, social, economic, political, and technological environments. He conceptualized tourism as an open system.

Neil Leiper’s Whole Tourism System Model

Neil Leiper devised a Whole Tourism System Model in the year 1979 and the same was restructured in the year 1990. It is completely based on the Systems Approach consisting of three major components or elements. The following are the four components embedded in the Leiper’s model.

Pic credit- https://www.slideshare.net/Poddar25/got-3-module-1

I. The Human Component:

The Tourist

II. The Geographical Component:

• The Generating Region

• Transit Route Region

• The Destination Region

III. The Industrial Component

Iv. the environmental component.

Leiper proposed six aspects within the model which are interrelated, interdependent and interact with each other and function as a group while responding to the external influences. Thus it is an open system where influences are found within the system as well as external to the system.

The human component consists of the tourists, the geographical component consists of traveler-generating regions, transit route regions and tourist-destination regions, the industrial component involving the various business and organizations that provide services and finally, the environmental component comprising of the social, technological, legal and ecological aspects.

All these aspects weave together as a whole tourism system in a structural manner. Figure-1 provides the pictorial representation of the Leiper’s model of the components of the tourism system.

1. The Human Component

The human component specified in the model is the tourists who undertake tourism to a destination of their interests. A tourist is a person who traverses away from his place of residence to another place for a short span of stay with an aim to spend his holidays.

A person can be called as a tourist if he stays for at least 24 hours and not more than one year in a destination either within the country or outside the country of residence not involving in any remunerative activity. Tourism, according to the Oxford dictionary, is “the theory and practice of touring or travelling for pleasure”.

Tourists undertake different forms of tourism as per their need like recreation, pleasure, business, education, health, pilgrimage, culture and they are called as recreational tourists, pleasure tourists, business tourists, education tourists, health tourists, pilgrimage tourists and cultural tourists in that order.

It is based on the motivational push that tourists undertake their trip to a particular destination. It all happens with the available forms of tourism. Therefore, it completely depends on the purposes of travel.

As per the definition of UNWTO’s (United Nations World Tourism Organization), “tourism comprises the activities of persons travelling to and staying in places outside their usual environment for not more than one consecutive year for leisure, business, and other purposes”. It is clear from the definition that tourists are temporary residents of the destination of visit.

After touring, they return to their original place of residence or their place of departure. According to Leiper (1979), the fundamentals of tourism are traced back to Greek origins, likened to a circle, reflecting a key component of tourism and returning to the point of departure.

2. The Geographic Component.

The geographic component refers to the geographical area involved in the tourism process. Tourists depart from a geographical area – the place of origin, utilize a geographical route and reach a geographical area – the place of arrival or destination of visit.

Similarly, they reach their area of origin after completion of the trip taking a complete cycle of the geographical components. Thus, there are three geographical areas involved in the conduct of tourism.

The geographic components comprise of the following three aspects:

1. Tourist Generating Region(TGR)

2. Travel Route Region(TRR) and

3. Tourist Destination Region(TDR)

2.1 Tourism Generating Regions (TGR).

Tourism Generating Region refers to the place where the tourist starts and ends his tour. It is the location of permanent residence from where he departs for tour and reaches after completion of trip. It is also referred to the source region of journey as well as the geographical area of demand. According to Dann (1977), it is the geographical setting pertaining to the motivational and behavioral pattern termed as “Push” factors.

‘Push’ factors are the intangible wishes or desires arising in the minds of a person. These are influenced by the social, psychological, and economic forces generated from within the person.

The aspects like mundane environment, exploration, self-evaluation, relaxation, prestige, family relations, and social interaction are found within the minds of the people of the tourist-generating region. These pertain to the psychological push factors. Influence of family, reference groups, social classes, culture, and sub-cultures are the factors pertaining to the social push factors.

The demographic aspects like age, sex, educational qualification, income and marital status also contribute to the push factors. The economic push factors are the disposable income added with the available leisure time joint together that play vital role in the tourist-generating region.

Apart from the above mentioned factors in the tourist generating region, the aspects like ticketing services, tour operators, travel agents and marketing and promotional activities present in the departure area play a major role as push components.

2.2. Transit Route Region (TRR).

Transit route refers to the path throughout the region across which the tourist travels to reach his or her destination. It is the path that links the tourist generating regions and the tourist destination regions, along which the tourists travel.

When the tourists undertake a long haul, travel it is necessary to take a temporary stoppage called a transit route. The transit route includes stopover points, which might be used for convenience of the tourist or due to the presence of various attractions throughout the travel route that can be visited by the tourists.

The transit route enables the tourists to change flight or stop for some time for refueling. The transit route might differ from the start of the travel from the generating region and ending of the travel from the destination region.

The transit route may be crossed with the different types of transportation like air transport or rail transport or water transport or road transport or a combination of all these types of transports according to the necessity of the tourist. Thus, the transit rout region is a vital component in the tourism system.

2.3 Tourist Destination Region (TDR).

Tourist Destination Region refers to the destination, which the tourists prefer to visit during their travel. It is the location, which attracts tourists for their temporary stay. The destination region is the core component of tourism, as it is the region, which the tourist chooses to visit, and which the core element of tourism is based on. It is the supply side of the tourism products that pull the tourists.

This component includes the natural attractions, cultural attraction, and various entertainment factors, accommodation, facilities, services, amenities, safety and security available in the destination of visit that ultimately pull the tourists. The new age tourists mostly demand now-a-days special interest tourism products available in the destination region.

The qualitative aspects that are absent or lacking in the tourist-generating region and available in the tourist destination region form as the basic attractions that pull the tourists towards TDR. The location has the attributes as anticipated by the tourists that retains loyal tourists from the generating regions

3. The Industrial Component..

The next important component in the Lieper’s model is the industry. Industrial component refers to the businesses and organizations that promote tourism related products. These firms thrive to cater to the needs and wants of the tourists.They impart full-fledged products and services to the tourists through attractions, accommodation, accessibility and amenities.

It is a composition of many small firms that provide tourist attractions and services to the tourists in an affordable manner. Tourism industry is not an individual entity and all the industrial components of the tourism industry function together as an amalgam as tourism cannot function in the absence of even a single aspect of the industrial component. Tourism industry is a mixture of many industries. They are:

• Tourist Services Industry

• Accommodation Industry

• Transport Industry

• Entertainment Industry

• Tourist Attraction Industry

• Shopping Industry

These industries are located in different places some in the tourist generating region and some in the destination region. The travel agents and tour operators are located in the tourist generating region who help in the arrangement of travel for the tourists.

They do marketing activities motivating the tourists to visit specific destination regions while designing tailor made tourism products. The travel agents and tour operators in the destination region are facilitators of the tourists. Thus, they form to be the tourist services industry.

The accommodation industry, the sub-component comprises of hotels, motels, resorts, guest- houses and home stays that provide temporary residential facility for the tourists. There is variety of options in the accommodation sector affordable to the different category of tourists. The transport industry consists of four forms of transport like air, rail, sea and road transport.

A number of carriers are there in the transport industry transporting the tourists from the tourist-generating region to the tourist destination region through the transit route region. It is one of the most indispensable components as tourism cannot happen without movement of people and transport industry solely takes care of it.

The entertainment industry pertains to the products provided in the destination region by the service providers with a motive to bring enjoyment, pleasure, fun, excitement, amusement and recreation to make the tourists’ leisure time fruitful and lively. Theaters, games, sports, gambling, bars and pubs are some of the products in the entertainment industry available in the destination region

The attraction industry comprises of the tourism experiences based on which tourists ultimately gets high level of satisfaction. Nature, culture, heritage, monuments, climate, beaches, events, sunshine, snow, are some of the attractions which pull the tourists towards the tourist destination region. Attractions are unique to the destinations, as these will not be found in the tourist-generating region.

Shopping Industry is another sub-component, which is unique to the destination region as tourists wish to shop products that are traditional or famous to that particular destination. For example, Kashmir is famous for shawls and Gujarat is famous for saris.

Therefore, tourists wish to buy souvenirs from the destinations and wherever they travel, they desire to go to some of the shopping malls to buy their choice products selected from souvenirs which happen to be ready-made wear, cosmetics / skin-care products, snacks / confectioneries, shoes/ other footwear, handbag /wallets/belts, souvenirs / handicrafts, medicine/ herbs, perfume, personal care and jewelry.

4. The Environmental Component.

The last component in the Leiper’s model of tourism system is the environment component that surrounds the three geographical regions. Tourism is an open system and it interacts with the external environment. Environment is the surrounding circumstances that affect the tourism system and vice versa. These forces either induce positive or negative influences on the tourism system. The environmental components that affect the tourism system are as follows:

1. Political Factors

2. Economic Factors

3. Social/Cultural Factors

4. Technological Factors

5. Environmental Factors

6. Legal Factors

4.1 Political Factors

Political factors influences the tourism system according the available political situation. An unstable political situation will hamstring the tourism development. Tourism system will function effectively if there is political harmony and law and order are executed in a proper manner.

It will further get developed in case the government enforces tourism policy planning, makes more investments in the tourism industry and ensures tax benefits. If there is good relationship existing between the countries of the tourist generating region and tourist destination region tourism will flourish. Otherwise tourism growth will be adversely affected.

4.2 Economic Factors

The economic factors influence the system of tourism as it is directly related to the per capita income of the tourist generating region, their disposable income and standard of living. On the other hand if tourist destination region provides affordable tourism products and services tourism development is likely to go up.

Therefore, the income and expenditure of the tourists will be balanced ensuring tourist flow. Economic factors are also directly related to the general global financial situation. The financial depression that was prevalent in the year 2008 had severely affected the tourism industry as the per capita income decreased all over the world.

4.3 Social/Cultural Factors

Social or cultural factors spell significant influences on the tourism system. Based on the attitude of the local people in the tourism destination region the tourists of the generating region will be pulled towards it. The experience of the tourists depends upon the receptive nature of the hosts of the destination.

If aversion prevails over the behavior of the tourists in the minds of the host people, loyal tourists cannot be pulled by the destination region. The tourists will not prefer to visit a destination which is not tourist friendly.

4.4 Technological Factors

Technology is another important factor that affects the tourism system. Technology has been developing swiftly and it has spread its wings in all the sectors especially in tourism. It has changed the travel behavior of the tourist of the generating region and the organizations of the tourism industry are using technology to market their their services and products of the tourist destination region.

Internet is used by the tourists to gather information about the destinations, the transit routes and the attractions to decide on their travel. They make reservations online instead of approaching the travel agents and tour operators – traditional methods of distribution system. The suppliers of the destination region and the transit route region like the airlines, hotels, and tourism attraction operators make direct contact with the tourists generating region and create great challenge to the intermediaries.

4.5 Environmental Factors

The environmental factors are related to the rich biodiversity existing in the tourist destination region. The more the pressure given to the environmental chasteness more will be the impact on the biodiversity. The ecosystem of the destination region is affected by the tourists of the generating region and the tourism industrial operators.

Negative impacts like pollution, loss of greeneries, congestion, over utilization creates the imperatives for making tourism sustainable for the future. Therefore, such negative impacts have to be eliminated or reduced by the government creating awareness about sustainability of tourism resources in the minds of the stakeholders otherwise severe loss will be exerted on the tourism system.

4.6 Legal Factors

The legal factors refer to the prevalent law and order in the tourist generating region, transit route region and the tourist destination region. These laws act as a framework to protect the tourists and the organizations of the tourism industry. It leads to the proper development and management of tourism and the components of the tourism system. There are laws pertaining to tourism infrastructure, conservation of natural rich biodiversity and the cultural resources.

You Might Also Like

World Tourism Day

Tour Guiding in a museum

Types of Meals Served in Airlines

This post has 8 comments.

Pingback: ¥¹©`¥Ñ©`¥³¥Ô©` ¥°¥Ã¥Á ¥©`¥±©`¥¹

Pingback: My Site

Pingback: AQW

Pingback: Adventure Quest Worlds

Pingback: ¥¹©`¥Ñ©`¥³¥Ô©` ¿Ú¥³¥ß 620

Pingback: ¥·¥ã¥Í¥ë ¥¢¥¯¥»¥µ¥ê©` ¥¹©`¥Ñ©`¥³¥Ô©`

Pingback: 時計 スーパーコピー 知恵袋

Pingback: ブランドバッグコピー

Comments are closed.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Tourism Theory Case Study Critique (Leiper's (1995) Whole Tourism System model

Critique of Neil Leiper's 1995 work on the Whole Tourism System model

Related Papers

C. Michael Hall

The Contribution of Neil Leiper to Tourism Studies C. Michael Hall, Department of Management, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, 8140, New Zealand; [email protected] Stephen Page, Centre for International Business and Sustainability, London Metropolitan Business School, London Metropolitan University, 277-281 Holloway Road, London N7 8HN, UK; [email protected] Abstract Neil Leiper was an influential tourism scholar who died in February 2010. The paper provides a review of his work and his contribution to tourism studies. Four major themes are identified from the time of his first major publication in 1979 up until his death: tourism systems, partial industrialisation, tourist attraction systems and strategy. Works in the first three areas are identified as having a significant influence on tourism literature and the conceptualisation of tourism as a discipline and the manner in which it is defined for both research and educational purposes. The connections between theory and strategy are noted which led to an important tourism text as well as the development of several cases of business failures, which Leiper argues is a significant subject for tourism education. The review concludes by identifying his legacy for the study of tourism. Keywords: Neil Leiper, tourism systems, partial-industrialisation, tourist attraction systems, discipline of tourism. This is a final draft of the manuscript. For the authoritative version please consult the website of Current Issues in Tourism. (Steve and I first met Neil at a tourism geography conference in New Zealand in 1988. Michael also worked with Neil at Massey University, where Stephen also worked in the 1990s. Although not seeing each other as much as we used to all of us had regular correspondence and exchange of ideas as well as providing other support. Many thanks also to John Jenkins for reading the draft for us)

Journal of Business on Hospitality and Tourism

Kadek Wiweka

Tourism within the practical scope has gone beyond the development of tourism theory itself. Considering the importance of theory as a foundation for knowledge and understanding of a phenomenon, especially in the scope of tourism. Therefore this study attempts to fill the gap between the tourism theory that has been built with the latest empirical facts. In developing tourism theory, this research used the creation of theory approach. Where in the process, the creation of theory is more inductive (or can be regarded as a qualitative approach). The result of this research is that tourism as a system consists of two kinds of subsystem that is internal and external subsystem. The internal subsystem is the interaction between person or the tourist termed as the tourist demand, from the tourist generating region and during a trip to a destination called the tourism supply, linked by the intermediaries elements, to return to its original territory. While external subsystem consists of international trade factors, safety and security factors, natural or climate factors, social-cultural factors, technological factors, economic or finance factors, political factors, demographic, and geographical factors. The relationship between the internal and external subsystems not only determined the existence of tourism, but otherwise the existence of tourism can also affect the two subsystems (internal and external). The interesting thing about this research is that the phenomenon of tourism can be 'limited' by its own point of view which is described through a comprehensive and integrated system. Keywords: Tourism system, Model and Framework, Theory building, Theoretical and Empirical perspective "I have no clue how I develop theory. I don't think about it; I just try to do it. Indeed, thinking about it could be dangerous" (Mintzberg, 2005)

Holly Donohoe

Dimitrios Stergiou

Purpose: This paper explores perceptions of tourism theory and its usefulness to the professional practice of tourism management as identified by the two major stakeholder groups – academics and tourism practitioners. Design/methodology/approach: Data for this study were collected through the use of two electronically administered surveys with tourism academics teaching on undergraduate tourism programmes of study and tourism professionals, both based in the UK. Findings: Findings suggest that tourism theory is important in understanding tourism itself. But at the same time it has pragmatic relevance, facilitating researchers and others to make sense of the real world and contributing to successful practice in tourism. Originality/value: This is the first study to provide empirical data from both academic and practitioner perspectives into often contested debates about the nature and uses of tourism theory.

Review of Economic Analysis

Jorge Ridderstaat

The literature on tourism development has focused on a one dimensional relationship between tourism development and quality of life. The impact of shock events on the relationship tourism development and quality of life seems ignored. Rather less attention has been paid to the multi-dimensional aspects of the relationship between tourism development and quality of life, and the potential impact of shock events on shaping this relationship. This study proposes a conceptual framework describing a triad of relations between tourism development (TD), quality of life (QoL) and shock events, and advocates that a bilateral relation exists between these three constructs. The framework also integrates three types of theories, each of which with the potential to explain tourism growth from a different perspective. The study analyzes a number of challenges facing tourism and discusses how these challenges interact and affect the interconnectedness between TD, QoL and shock events. The dynamic ...

A Companion to Tourism

Tourist Studies

ERCAN AKKAYA

Lazar Kalmic

The main subject of analysis in this paper is the issue of change of the dominant paradigm in the study of tourism. In this sense, first the following key categories are being examined: pre-paradigmatic stage, paralysis, transformation or paradigm shift, borrowing and adaptation of theories from other disciplines and their applications in tourism. Then, the tourist system is being analyzed in detail, which is still the dominant paradigm, and which provides a coherent conceptualization of tourism. In contrast, there is postmodernism, which stands for discontinuity and deconstruction of existing theories and systems. This is, in fact, a post-disciplinary approach that insists on the demolition of the walls between the individual disciplines, i.e. on “forgetting separate disciplines,” and puts exclusively the research of a certain phenomenon in this specific case, tourism, in the spotlight. Also, it is strived for complete dedication and specialization of researchers, as well as the re...

RELATED PAPERS

IOSR Journal of Pharmacy

Automation Control - Theory and Practice

Omar Lengerke

Iván S A M B A D E Baquerín

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology

The proceedings of the 13th international conference "Modern Building Materials, Structures and Techniques" (MBMST 2019)

João Victor Schmicheck

Richard Potts

UK B A N K FULLZ

MEDIA ILMU KESEHATAN

Meida Ramdani

INVOTEK: Jurnal Inovasi Vokasional dan Teknologi

Febri Prasetya UNP

Dermatologic Surgery

ricardo luna

PKL TANGERANG

Rizky Wisnu

Ilham Ramadhan

Anna Steidle

International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering

Bernard Haasdonk

Min-shan Chen

zaharah abd samad

Polish Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences

Boredi S I L A S Chidi

ICTACT JOURNAL ON SOFT COMPUTING

vikranth kadya

Journal of electroanalytical chemistry and interfacial electrochemistry

halim Abdurrachim

Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development

Guy Bodenmann

Frontiers in Pain Research

Anuj Bhatia

TURKISH JOURNAL OF MATHEMATICS

Selami ERCAN

Journal of Foreign Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics

Marjana I Kalan

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting

Eliab Korir

Virtual Reality: A Simple Substitute or New Niche?

- Victoria-Ann Verkerk ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5314-9106 4

- Conference paper

- Open Access

- First Online: 07 January 2022

19k Accesses

4 Citations

Since 2020, the tourism industry worldwide has been devastated as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments across the globe imposed strict national lockdowns in order to curb the spread of the pandemic, with negative effects on tourism. This forced many tourism companies and organizations to turn to virtual reality (VR) to survive. As a consequence, numerous tourism scholars began to question whether VR would replace conventional tourism after COVID-19. The study aims is to address this concern and to determine if VR will be a substitute for conventional tourism or whether it can be considered as a tourism niche. It is a conceptional study which adopts a comparative analysis of conventional tourism models and VR. It uses two popular conventional tourism models, namely N. Leiper’s (1979) tourism system model and R.W. Butler’s (1980) destination life-cycle model. Based on this analysis, this paper suggests that VR will never be a substitute for conventional tourism, but should rather be considered a future tourism niche.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

1 Introduction

Tourism has faced several crises in the past [ 9 , 14 ], however, none of these have had such an impact on tourism as the novel coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) [ 14 ]. To try to minimize the spread of the virus, the majority of governments have implemented non-pharmaceutical measures, such as quarantine, lockdowns, physical distancing, canceling events, and closing land borders to tourists [ 2 , 9 , 14 ]. This caused the tourism industry to come to a literal halt [ 14 ]. The United Nations World Tourism Organization estimated that by the end of 2020, international tourist arrivals declined between 70% to 75%, and as a result, tourism revenue dropped by US$711.94 billion to US$568.6 billion, which represented a loss of 20% [ 20 , 28 ].

It is difficult to predict when, and if, tourism will ever really recover from COVID-19. It is estimated by some that it will take the tourism industry up to 10 months to recover after the pandemic [ 8 ]. Therefore, it is argued that international tourism will only return between 2021 and 2022 [ 28 ]. But the recovery of tourism could take even longer. For example, it took tourism 4.5 years to recover after the 9/11 terrorist attack [ 26 ]. Thus, tourism scholars argue that technology will play a critical role in building resilience in tourism. One such technology is virtual reality (VR) [ 1 , 14 ].

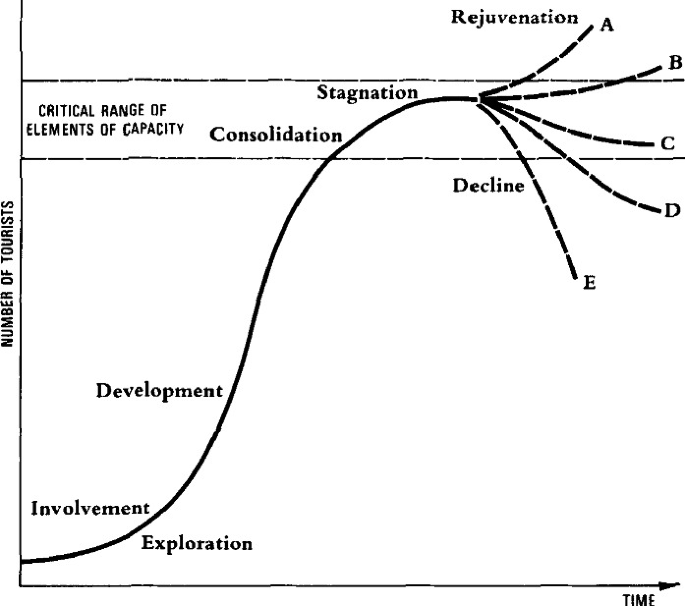

In light of this, tourism scholars have begun debating whether VR will act as a substitute for conventional tourism once the COVID-19 pandemic is under control or is over. This study, however, considers whether VR can be regarded as a substitute for conventional tourism or a tourism niche. This will be determined by comparing the most renowned conventional tourism models with VR, namely: N. Leiper’s tourism system model (1979) and R.W. Butler’s destination life-cycle (TALC) model (1980).

2 Virtual Reality in Tourism

The tourism industry has used VR since the 1990s [ 4 , 15 ]. Despite this, there is no precise definition of VR in tourism literature [ 3 ]. Scholars often rely on and cite the well-known definition of D.A. Guttentag [ 15 ]:

the use of a computer-generated environment [the virtual environment] that one can navigate [the ability to move and explore the virtual environment] and possibly interact [to the ability to select and move objects within the virtual environment] with resulting in real time simulation of one or more of the user’s five senses.

According to Guttentag, there are six main areas where VR provides benefits in tourism, namely: marketing; planning; sustainability and preservation; accessibility; education; and entertainment [ 15 ]. For many tourism scholars, VR is also seen as a benefit to tourism, however, they generally tend to focus on two of these areas, namely marketing and sustainability. In terms of marketing, tourism companies and organizations perceive VR as a superior marketing tool. In fact, VR has been described as having revolutionized the way tourism products, services, and experiences are promoted and sold [ 21 , 29 ]. For example, Tussyadiah et al. [ 27 ] state that VR offers potential tourists a “try before buy” experience, which enables them to experience a destination virtually beforehand [ 7 ]. This is beneficial as it might encourage potential tourists to physically travel to the actual destination [ 15 ].

Tourism scholars and practitioners also regard VR as an ideal sustainable tool. As tourists and tourism-related activities have led to over-tourism, many tourism destinations/sites, especially those that are fragile and sensitive, have been restricted to tourists. However, VR enables tourists to gain “access” to these destinations/sites, without causing physical harm or degradation to the actual destination/site. According to tourism scholars, the reason is that VR provides tourists a substitute, or alternative, version of the real destination/site [ 7 , 15 , 29 ].

On the other hand, for many tourism scholars, VR poses a threat to tourism. According to this view, the major drawback of VR is that it is an individual activity that does not allow tourists any physical interaction with the local community or other tourists. This is a major concern as interaction plays an integral part in the tourist experience as people are social beings that want to be in the company of others [ 7 , 24 ]. Even though VR can motivate potential tourists to visit the physical destination, it could replace the need to travel - having COVID-19 enhance this. VR might even offer potential tourists a better tourist experience than the real one. This means that potential tourists no longer have the desire to travel to the actual destination. For many countries that are dependent on tourism revenue, specifically those in the global South, this is detrimental as it may lead to them suffering economically [ 7 , 23 ].

Despite these benefits and drawbacks which permeate the scholarship, there is a major gap in the literature as tourism scholars have not yet paid adequate attention to VR as a tourism niche in its own right, but rather as a substitute for conventional tourism. The purpose of this study is, thus, to address the gap, as well as determine whether VR can be regarded as a substitute for conventional tourism or as a tourism niche.

3 Literature Review

As indicated, the literature on tourism and VR is relatively limited, with only certain aspects having received any attention. It is apparent that the literature on tourism and VR has essentially focused on select key aspects: marketing, sustainability, VR as a substitute for conventional tourism, and COVID-19. Marketing has been a popular area in VR literature during the last three decades [ 17 ]. This is indicated by the wide range of topics, which include some of the following: VR compared with traditional marketing media (e.g., travel brochures) [ 21 ], presence [ 27 ], and Second Life [ 18 ].

Tourism scholars have also discussed how VR can be used as the ultimate tool for sustainability. One of the most-cited authors in this regard is J.M. Dewailly who focuses on how VR contributes to sustainability in tourism [ 11 ].

Another area that has become popular among tourism scholars is VR as a substitute for conventional tourism. In his latest publication, Guttentag discusses VR as a substitute for conventional tourism. He concludes that VR will never substitute conventional tourism [ 16 ]. In contrast, D. Sarkady et al. disagree by stating that although tourists used VR as a substitute for conventional tourism during COVID-19, they will also do so after the pandemic [ 25 ].

Lastly, since 2020, tourism scholars have begun paying attention to how VR can contribute to tourism during COVID-19. O. Atsiz, is one of many scholars that has addressed this topic, focused on how VR can offer tourists an alternative travel experience, while still adhering to physical distancing (or social distancing) regulations [ 2 ].

When considering tourism models, it is Butler’s TALC model which emerges as one of the most popular conventional tourism models in tourism literature. It has stood the test of time as tourism scholars continue to reference this model and his work as seminal. In addition, the conventional tourism framework model by Leiper is also often favored among tourism scholars.

In terms of VR, the only authors that have paid attention to a conventional tourism model thus far are J. Bulchand-Gidumal and E. William. In their work, they use Leiper’s tourism framework model for VR and augmented reality to discuss the main stages of travel - dreaming, planning, booking, transit, experiencing, and sharing. The results of their study show that VR is applicable in the following phases: dreaming (i.e., the “try before buy” concept), planning (i.e., the “try before buy” concept), booking (i.e., the “try before buy” concept), transit (i.e., entertainment), experiencing (i.e., the complete tourist experience), and sharing (i.e., social media) [ 5 ]. Given the limited attention this topic appears to have received, this study addresses this gap.

4 Methodology

As in the case of many tourism studies, this study does not use empirical research such as qualitative and quantitative research methods as it does not rely on experiments. Instead, it adopts a conceptual research approach and a comparative analysis. The conceptual research approach is of relevance as it is often used to address difficult questions and to “develop new concepts… or [to] reinterpret existing ones” [ 30 ]. A multiple comparative methodology was also adopted to more effectively “gauge the significance, validity and reliability of the outcome” [ 12 ]. The conventional tourism models devised by Butler and Leiper were selected as benchmarks based on the reason that they have remained popular and reliable since they emerged in the literature. Therefore, they still apply to modern-day tourism research. Another reason is that tourism is constantly changing, thus, the study compares two established conventional tourism models and argues that in doing so the position and status of VR within the tourism realm can be evaluated.

5 Results and Discussion

This section focuses on the conventional tourism models by Leiper and Butler and how they can be applied to VR. It is divided into two sections. The first section explains these models in terms of conventional tourism, and the second assesses the similarities and differences between VR and conventional tourism. In other words, it appraises the VR dimension in terms of the two key conventional tourism models.

5.1 Conventional Tourism Models

Over the past half-century, as tourism has evolved as a subject of intense academic research, a plethora of tourism-related models have been developed. This section briefly discusses the two conventional tourism models devised by Leiper and Butler that have been selected for this analysis as they have stood the test of time and are still regarded among tourism scholars as key analytical tools. In 1979, Leiper developed the “tourism system” model in order to understand and manage tourism (see Fig. 1 ). The model comprises of tourists, geographical elements (tourist generating region, the tourist destination region, and the transit and route region), and the tourism industry [ 19 ].

(Source: Leiper, Leiper, N. (1979) The framework of tourism towards a definition of tourism, tourist, and the tourist industry. Annals of Tourism Research 6(4):404)

The tourism system

According to Leiper’s model, the integral component in tourism is the tourists. Fletcher et al . [ 13 ] state that tourists “initiate the demand for travel for tourism purposes”. Thus, the tourism industry cannot function at all without them [ 19 ].

In terms of the geographical elements, they consist of the tourist generating region, the tourist destination region, and the transit and route region. Leiper states that the tourist generating region is “the place where tours begin and end”, in other words, tourists’ residences [ 19 ]. Based on the model, the tourist destination region refers to the area that tourists stay in temporarily, namely the destination [ 19 ]. Some scholars are of the opinion that the tourist generating region and the tourist destination region align with G.M.S. Dann’s “push” factors (the reason tourists want to travel) and “pull” factors (features of the destination that encourage tourists to travel to the destination) [ 10 ]. Based on the model, the tourist generating region “pushes” tourists to travel, while the tourist destination region “pulls” tourists to it [ 13 ].

Leiper states that the transit and route region include destinations tourists visit on route. The transit and route region are important factors in tourism as they link the tourist generating region and the tourist destination region with one another [ 19 ].

The last element in Leiper’s model is the tourism industry. According to him, the tourism industry includes the tourism organizations, companies, and facilities that serve tourists, for example, shops and restaurants [ 13 , 19 ].

Lastly, as indicated by Leiper, there are five external factors that influence the elements of the model, namely physical, cultural, social, political, and technological [ 19 ].

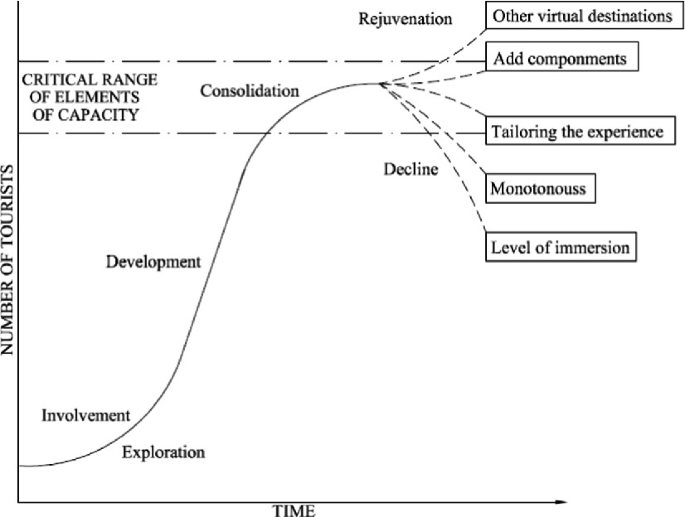

The second model, and one of the most cited in tourism literature, is the “TALC model” (see Fig. 2 ). In 1980, Butler developed the TALC model in order to showcase the different phases that a conventional destination undergoes. He argues that a conventional destination goes through various phases, including the exploration stage; the involvement stage; the development stage; the consolidation stage; the stagnation stage; the decline stage, and finally the rejuvenation stage [ 6 ].

(Source: Butler, R.W. (1980) The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer 24(1):7)

The tourist destination life-cycle

According to Butler’s TALC model, the first phase is the exploration stage. The destination is still unaffected by tourism and is mainly visited by ‘early tourists’, such as “explorers” (they want to get away from the so-called ‘beaten track’) and “allocentrics” (adventurous tourists). Since the destination is intact, there is physical interaction between the locals and the visitors. It is for this reason that visitors use local facilities as the infrastructure has not yet been developed for tourism [ 6 ].

The TALC model indicates that the second phase is the involvement stage. In the involvement phase, the destination becomes more popular among tourists as it is now being marketed. The locals begin to realize the potential of tourism and start to provide facilities to cater for tourists. It is also during the involvement phase that a tourism season emerges [ 6 ].

Butler states that the third phase in the TALC model is the development stage. The destination is still gaining popularity, especially among “mid-centrics” (they visit the destination during its “heydays”) and the “institutionalized tourist” (they prefer organized tours). However, the locals’ involvement begins to decrease, which opens the door to external tourism organizations. Unfortunately, the external tourism organizations begin to replace the locals and bring in auxiliary facilities, update the existing facilities, and import labor to cater for tourists [ 6 ].

The model shows that the next phase in Butler’s TALC model is the consolidation stage. The destination is now in its “heyday” as tourists are still increasing and its economy now depends on tourism. But increasingly tourists are no longer interested in the old facilities. Therefore, the external tourism organizations begin to replace the old facilities with newer and improved facilities. This leads to the locals opposing tourism [ 6 ].

The fifth phase in Butler’s TALC model is the stagnation stage. During this phase, the destination has finally reached its peak in terms of tourist numbers. Tourists still regard the destination as “old fashioned”. Only the “organized mass tourist” (who prefers flexible organized tours) and “psychocentric tourist” (who desires a well-developed and safe destination) travel to the destination. It is also at the stagnation phase that the natural and cultural attractions deteriorate and, therefore, external tourism organizations replace them with artificial facilities [ 6 ].

After the stagnation phase, a destination can either pass through the decline phase or the rejuvenation phase, or both. This depends on how popular the destination is among tourists. Regarding the decline phase, the destination is considered in a tourism slump due to overuse of resources or as a result of war, disease, or any other catastrophic event (as shown by Curves D and E). It is during the decline phase, that the locals begin to show renewed interest in the destination by visiting the destination and purchasing the facilities [ 6 ].

In terms of the rejuvenation phase, the destination can be restored to its former glory through successful redevelopment, minor modification, and adjustment to capacity levels, and protection of resources (as shown in Curves A, B, and C) [ 6 ].

5.2 Virtual Reality Tourism Models

It is argued that Leiper’s tourism framework and Butler’s TALC model can be used to highlight the similarities between conventional tourism and VR. This section substantiates this viewpoint.

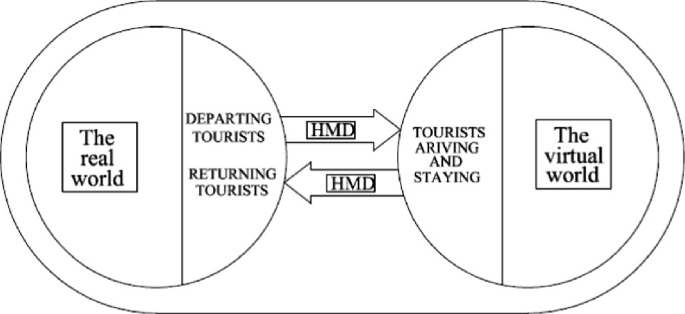

The study argues that Leiper’s tourism system is similar to the VR tourism system. The reason is that the VR tourism system also consists of the same core elements, namely tourists, geographical elements, and the tourism industry (see Fig. 3 ).

(Adapted from LeiperN. (1979) The framework of tourism towards a definition of tourism, tourist, and the tourist industry. Annals of Tourism Research 6(4):404)

The tourism system.

As indicated by Leiper’s model, tourists play a key role in conventional tourism. This is also the case with the VR tourism system. In VR, tourists (i.e., virtual tourists) are important as tourism companies and organizations rely on them to purchase and use their VR-related products and services. Therefore, similar to conventional tourism, it is impossible for VR to function properly without virtual tourists.

In terms of the geographical elements, VR also comprises of three elements similar to those referred to by Leiper. With regards to VR, the real world is considered as the tourist generating region. In the real world, tourists often face challenges and issues on a daily basis, for instance, the COVID-19 pandemic. The tourist destination region changes to the virtual world. As highlighted, the tourist generating region and the tourist destination region correspond with Dann’s push and pull factors. The reason is that the challenges and issues (e.g., COVID-19) “push” tourists, while the virtual world “pulls” them to it. This is because the virtual world offers tourists a temporary escape from their daily challenges and issues. In order to get to the tourist destination region, tourists “pass through” the transit and route region. In VR, the transit and route region equate to the head-mounted display (HMD). Similar to the conventional tourism model, it is noted that virtual tourists also travel from the tourist generating region (i.e., the real world) pass through the transit and route region through an HMD, and end up at the tourist destination region (i.e., the virtual destination).

Lastly, as regards to Leiper’s third aspect, the tourism industry, it is argued that in VR, this comprises of tourism organizations and outlets that order VR-related services and products from VR developer companies to offer tourists the VR tourist experience. It can, therefore, be concluded that Leiper’s model shows that VR is in many ways similar to conventional tourism.

The next conventional model is Butler’s TALC model. It is argued that a virtual destination also passes through most of the stages referred to by Butler in his TALC model as shown in Fig. 4 .

(Adapted from: Butler, R.W. (1980) The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer 24(1):7)

The first phase according to Butler, is the exploration stage. During the exploration phase, not many people are aware of the virtual destination. The only visitor that ‘travels’ to the destination is the “curious visitor” (who has an eagerness to explore the virtual destination on, for example, the internet due to his/her curiosity). The quality of the virtual destination is poor as tourism organizations provide a very basic or elementary virtual tour since it is cheaper for a start-up. The only downside in the exploration phase, unlike conventional tourism, is that VR does not offer tourists any physical interaction between the locals (i.e., VR developer companies) and the curious visitor, as indicated earlier.

The next phase in Butler’s TALC model is the involvement stage. Visitor numbers increase as they are becoming more aware of the virtual destination. For this reason, the local VR developer companies begin to show a keen interest in the virtual destination and begin to market it through, for instance, virtual advertisements on the internet. In addition, the local VR developer companies also start to improve the virtual destination by adding other elements, such as higher quality visuals and improved sound.

Following the involvement phase is the development stage. The virtual destination now attracts a new type of tourist, namely the so-called “virtual tourist” (they prefer to explore virtual destinations). It is at the development phase that the virtual destination is in its prime due to its popularity. As a result, there are more virtual tourists compared to the local VR developer companies. In fact, VR has the ability to attract more people than conventional tourism because, for instance, an app of the virtual tour can be downloaded or viewed by many people in comparison to conventional tourism which only allows a certain limited number of tourists according to physical capacity. Unfortunately, the local VR developer companies’ involvement can begin to decrease and they are then replaced by international VR developer companies. The international VR developer companies begin to change the virtual environment by upgrading and improving the virtual destination through integrating new components, such as an HMD.

The fourth phase in Butler’s TALC model is the consolidation stage. As indicated by the number of downloads or viewers, virtual tourist numbers are still increasing. In addition, the international VR developer companies transform the virtual destination from a basic 360° video/image virtual tour to a more immersive tour as they add new elements, such as movement (e.g., touch) and sound. The virtual destination begins to rely on the revenue gained from tourism. Hence, the international VR developer companies begin to charge fees for tourists to view the virtual destination. As a result, the local VR companies feel left out and retreat and often go bankrupt.

It is contended that a conventional tourism destination does not always pass through all the phases mentioned in Butler’s TALC model. This is also the case with VR. The phase that does not apply to the virtual destination is the stagnation stage. The reason is that a virtual destination will never experience a peak in tourist numbers, cannot be destroyed, and suffer as a result of other issues (i.e., environmental, social, and economic). Moreover, the virtual destination does not have to rely on repeat visitation and lower-income tourists as, unlike a conventional tourism destination, it does not rely on repeat visitation because it is able to attract new and potential tourists regularly.

After the consolidation phase, the virtual destination can pass through the decline phase or the rejuvenation phase, or both. In a sense, the virtual destination does not always experience the decline phase. Again, the reason is that the virtual destination does not exist. Therefore, the virtual destination does not face the same issues as a conventional tourism destination would. However, if the virtual destination does experience the decline phase, it might start to lose tourists due to the tourist experience becoming monotonous and boring, or the level of immersion (as shown by Curves D, and E). In addition, the local VR companies might be involved again in the development of the virtual destination. Lastly, the virtual destination will mainly be visited by attitudinal loyal tourists (they show affection towards a certain brand) and behavioral loyal tourists (they continually use or buy the same brand) [ 22 ]. In terms of VR, attitudinal loyal tourists are considered poor tourists. They are loyal to the virtual destination since they cannot afford to travel to the actual destination. Behavioral loyal tourists in VR are wealthy tourists that will only visit the virtual destination in order to decide whether it is worth it to visit the actual destination beforehand.

Should the virtual destination experience the decline phase, it can attract tourists again in the rejuvenation phase. VR developers can achieve this by offering tourists another aspect of the virtual destination, make the virtual tour more immersive by adding other components or to tailor the experience according to the need of the tourist (as shown in Curves A, B, C). Therefore, the study argues that the VR destination can be seen to undergo most of the phases that a conventional tourism destination undergoes according to Butler’s TALC model.

6 Conclusion

As COVID-19 has devastated the tourism industry, many tourism companies and organizations were forced to move to VR in order to survive. VR literally transformed the tourism industry, especially in terms of marketing and sustainability. Therefore, the aim of the study was to determine if VR could become a substitute for conventional tourism or whether it can be considered as a tourism niche, especially in the future. A conceptual and comparative analysis was conducted by comparing two of the most popular conventional tourism models with VR, namely Leiper’s tourism system and Butler’s TALC model.

Based on the results, VR will not likely be a substitute for conventional tourism. It is, therefore, argued that VR should rather be considered as a tourism niche in its own right. In fact, the conventional tourism model by Leiper supports this. As indicated, VR also consists of similar elements mentioned in Leiper’s model, namely tourists, geographical elements, and the tourism industry. Similar to Leiper’s conventional tourism system model, in VR, virtual tourists are also regarded as vital as the industry relies on them. In terms of the geographical elements, virtual tourists also have to pass through the tourist generating region (i.e., their reality), the tourist destination region (i.e., the virtual world), and the transit and route region (i.e., HMDs). Lastly, the tourism industry in VR is considered to be the tourism organizations and companies that rely on VR developer companies to develop a VR tourist experience for them to sell to virtual tourists.

Even Butler’s TALC model shows that VR is similar to conventional tourism. Based on the model, a virtual destination (i.e., a simple 360° video/image or live-stream tour of an actual or fabricated destination) also passes through many of the phases, especially the exploration stage; the involvement stage; the development phase; the consolidation phase; the decline phase and the rejuvenation phase. However, the only phase that does not apply to VR is the stagnation stage. Compared to a conventional tourism destination, the virtual destination is virtual, in other words, not “real”. Thus, the virtual destination will never experience its peak in tourist numbers, destruction, and issues.

Lastly, in order for VR to be considered as a tourism niche in the future, two problems need to be addressed by future scholars. The first major issue is that VR does not entail any physical interaction between the local VR developers and virtual tourists. As indicated, it is important to address the issue because interaction plays a key role in the tourism domain as humans are considered social beings. The second vital issue that has to be focused on is that VR does not provide tourists the full tourist experience as in the case of conventional tourism, where tourists are able to experience a destination through all of the five senses (i.e., sight, sound, smell taste, and touch). This issue needs serious attention because a full sensorial tourist experience will result in a more authentic experience for tourists. For now, VR appears, thus, not to be a substitute for conventional tourism, but rather as a dynamic futuristic niche in its own right.

Akhtar N et al (2021) Post-COVID 19 tourism: will digital tourism replace mass tourism? Sustainability 13:5352–5370. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105352

Article Google Scholar

Atsiz O (2021) Virtual reality technology and physical distancing: a review on limiting human interaction in tourism. J Multidiscip Acad Tour 6:27–35. https://doi.org/10.31822/jomat.834448

Beck, J http://www.virtual-reality-in-tourism.com/try-before-you-buy-with-expedia/

Beck J, Rainoldi M, Egger R (2019) Virtual reality in tourism: a state-of-the-art review. Tour Rev 74:586–612. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-03-2017-0049

Bulchand-Gidumal J, William E (2020) Tourists and augmented and virtual reality experiences. In: Xiang Z, Gretzel U, Höpken W (eds) Handbook of e-tourism. Springer, Cham, pp 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05324-6_60-1

Butler RW (1980) The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: implications for management of resources. Can Geogr 24:5–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.1980.tb00970.x

Cheong R (1995) The virtual threat to travel and tourism. Tour Manag 16:417–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(95)00049-T

Chirisa I et al (2020) Scope for virtual tourism in the times of COVID-19 in select African destinations. J Soc Sci 64:1–13. https://doi.org/10.31901/24566756.2020/64.1-3.2266

Gössling S, Scott D, Hall M (2020) Pandemics, tourism and global change: a rapid assessment of COVID-19. J Sustain Tour 29(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.31901/24566756.2020/64.13.2266

Dann GMS (1981) Tourist motivation an appraisal. Ann Tour Res 8:187–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(81)90082-7

Dewailly JM (1999) Sustainable tourist space: from reality to virtual reality? Tour Geogr 1:41–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616689908721293

Domínguez-Mujica J (2016) Comparative study. In: Jafari J, Xiao H (eds) Encyclopedia of tourism. Springer, Cham, pp 174–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01384-8

Fletcher J, Fyall A, Gilbert D, Wanhill S (2018) Tourism: principles and practice, 6th edn. Pearson, Harlow

Google Scholar

Gretzel U et al (2020) e-Tourism beyond COVID-19: a call for transformative research. Inf Technol Tour 22(2):187–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00181-3

Guttentag DA (2010) Virtual reality: applications and implications for tourism. Tour Manag 31:637–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.07.003

Guttentag DA (2020) Virtual reality and the end of tourism? A substitution acceptance model. In: Xiang Z, Gretzel U, Höpken W (eds) Handbook of e-tourism. Springer, Cham, pp 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05324-6_113-1

Hopf J, Scholl M, Neuhofer B, Egger R (2020) Exploring the impact of multisensory on VR travel recommendation: a presence perspective. In: Neidhardt J, Wörndl W (eds) Infor-mation and communication technologies in tourism 2020. Springer, Cham, pp 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36737-4

Huang YC, Backman KF, Backman SJ, Chang LL (2016) Exploring the implications of virtual reality technology in tourism marketing: an integrated research framework. Int J Tour 18:116–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2038

Leiper N (1979) The framework of tourism towards a definition of tourism, tourist, and the tourist industry. Ann Tour Res 6:390–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(79)90003-3

Lock, S https://www.statista.com/topics/6224/covid-19-impact-on-the-tourism-industry/

McFee A, Mayrhofer T, Baràtovà A, Neuhofer B, Rainoldi M, Egger R (2019) The effects of virtual reality on destination image formation. In: Pesonen J, Neidhardt J (eds) Infor-mation and communication technologies in tourism 2019. Springer, Cham, pp 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05940-8

Mechinda P, Serira S, Gulid N (2009) An examination of tourists’ attitudinal and behavioral loyalty: comparison between domestic and international tourists. J Vacat Mark 15:129–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766708100820

Musil S, Pigel G (1994) Can tourism be replaced by virtual reality technology? In: Schertler W, Schmid B, Tjoa AM, Werthner H (eds) Information and communications technologies in tourism. Springer, Vienna, pp 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-7091-9343-3_14

Prideaux B (2002) The cybertourist. In: Dann GMS (ed) The tourist as a metaphor of the social world. CABI, Wallingford, pp 317–339. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851996066.0000

Sarkady D, Neuburger L, Egger R (2021) Virtual reality as a travel substitution tool during COVID-19. In: Wörndl W, Koo C, Stienmetz JL (eds) Information and communication technologies in tourism 2021. Springer, Cham, pp 452–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65785-7

Smith, C https://www.news24.com/fin24/companies/travelandleisure/tourism-industry-doubles-down-to-reassure-travellers-20200606-2

Tussyadiah IP, Wang D, Jung TH, tom Dieck MC (2018) Virtual reality, presence, and attitude change: empirical evidence from tourism. Tour Manag 66 , 140–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.12.00

United Nations World Tourism Organization. https://www.unwto.org/impact-assessment-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-on-international-tourism

Williams AP, Hobson JSP (1995) Virtual reality and tourism: fact or fantasy? Tour Manag 16:423–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-5177(95)00050-X

Xin S, Tribe J, Chambers D (2013) Conceptual research in tourism. Ann Tour Res 14:66–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.12.003

Download references

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank her supervisor, Prof K.L Harris (Head of Department of the Historical and Heritage Studies and Director of the University of Pretoria Archive) for all her support and guidance during the writing of this paper. The author wishes to thank the University of Pretoria for granting her the necessary funds for her Ph.D. research. Moreover, the author thanks her family and friends for their support. Lastly, the author thanks the ENTER Conference for the opportunity.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Pretoria, Pretoria, 002, South Africa

Victoria-Ann Verkerk

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Modul Private University Vienna, Wien, Wien, Austria

Jason L. Stienmetz

University of Lleida, Lleida, Spain

Berta Ferrer-Rosell

Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, Bolzano, Italy

David Massimo

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Verkerk, VA. (2022). Virtual Reality: A Simple Substitute or New Niche?. In: Stienmetz, J.L., Ferrer-Rosell, B., Massimo, D. (eds) Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2022. ENTER 2022. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94751-4_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94751-4_3

Published : 07 January 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-94750-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-94751-4

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The benefits of Leiper's Tourism System . There are many benefits of Leiper's tourism system. Leiper's model allows for a visual depiction of the tourism system. The model is relatively simple, enabling the many to comprehend and use this model. Leiper's Tourism System model has been widely cited within the academic literature and ...

Neil Leiper's Whole Tourism System Model. Neil Leiper devised a Whole Tourism System Model in the year 1979 and the same was restructured in the year 1990. It is completely based on the Systems Approach consisting of three major components or elements. The following are the four components embedded in the Leiper's model.

Leiper's tourism system is one of the most well cited tourism theories. By defining tourism not as a single entity, but instead as a system, Leiper's tourism...

Collectively, these elements denote that tourism runs as a system ( Figure 2.1) as postulated by the widely used Leiper's Model (Fletcher et al., 2018; Hall & Page, 2010; Holden & Fennell, 2012 ...

According to Leiper 5 such a metaphorical description could actually hinder effective research on tourism and instead he advocated an alternative approach to encourage better thinking about the role of destinations in tourism systems. Leiper's (2000b) analysis has been gradually influencing thinking about the nature of destinations in tourism ...

And of course, his foundation work in whole tourism systems (WTS) has been used as a foundation for understanding tourism for decades and continues to be an early chapter in most introductory tourism textbooks (Backer, 2010). Accordingly, Neil's WTS models have "become a common organising framework for the study of tourism" (Backer, 2010, p.