You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

- Section 9 - Sex & Travel

- Section 10 - Egypt

African Safaris

Cdc yellow book 2024.

Author(s): Kate Varela, Juliet Kasule, Joseph Ojwang, Aimee Geissler, Karl Neumann

Destination Overview

Infectious disease risks, environmental hazards & risks, safety & security, availability & quality of medical care.

Arguably the ultimate in adventure travel, an African safari is the experience of a lifetime. Safari-goers have options to view wildlife from different vantages: on land (traditional savannah guided car safaris, open trucks, air-conditioned vans, personal vehicles), on the water (in a dugout canoe), or from the air (private aircraft, hot air balloon). Hiking with trained, licensed guides in well-scouted settings offers another opportunity to see wildlife up close; treks to view chimpanzees or gorillas, for example, are highly popular.

With >150 game parks and reserves across the continent, individual travelers, families, backpackers, and people with similar interests (e.g., serious photographers) have a range of choices and budget options. Some parks are remote and rustic, with long drives to see the animals but with fewer tourists. Other parks are easily accessible with self-drive options. Many safaris accept young children and adolescent participants; gorilla trekking and other more strenuous activities require participants to be ≥15 years of age.

Map 10-01 and Map 10-02 show several major African game parks. In East Africa, the Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya is the northern extension of Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park game reserve. Together these 2 parks are home to the complete collection of the so-called big 5—Cape buffalo, elephants, leopards, lions, and rhinoceros—the large wild animals for which Africa is most famous. Other East African game parks that offer exceptional wildlife viewing include Tsavo National Park (Kenya); Akagera National Park (Rwanda); Ngorongoro Crater (Tanzania); and Ngamba Island Chimpanzee Sanctuary, Murchison Falls National Park, Queen Elizabeth National Park, and Ziwa Rhino Sanctuary (Uganda). Travelers can trek to see gorillas at the Virunga National Park (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Volcanoes National Park (Rwanda), and Bwindi Impenetrable National Park (Uganda); “impenetrable” refers to the challenging hiking required in this park.

Game park destinations in Southern Africa include Moremi Game Reserve, Chobe National Park, and Kalahari Desert (Botswana); Etosha National Park (Namibia); Kruger National Park (South Africa); Lower Zambezi National Park and South Luangwa National Park (Zambia); and the Hwange National Park (Zimbabwe). Pendjari National Park in Benin, home to West African lions and elephants, is a major part of the largest intact ecosystem in West Africa, the transnational W-Arly-Pendjari (WAP) complex, which spans Benin, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Mole National Park (Ghana) boasts >93 mammal species, including elephants and hippos.

Although the centerpiece of safari-going remains viewing majestic animals in their natural habitat, many tour operators now also offer programs on local culture and history, ecosystems, and geology. Conservation-based tours promoting responsible tourism give travelers an opportunity to help safeguard wildlife, protect vital habitat, and benefit local people.

Map 10-01 African game parks & reserves (North)

View Larger Figure

Map 10-02 African game parks & reserves (South)

Health, safety, and comfort issues that safari-goers are likely to encounter are mostly predictable and largely avoidable. A pretravel consultation with a travel health care provider is essential. Multiple vaccinations might be required for healthy safari travel. Provide advice specific to each traveler’s itinerary, country, and game park. Because vaccines take time to become effective, advise travelers to seek vaccination as early as possible prior to planned departure. For people trekking to see gorillas, certain vaccines are recommended to protect both travelers and animals, including coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis, hepatitis A and hepatitis B, influenza, measles-mumps-rubella, polio, and yellow fever.

Enteric Infections & Diseases

Hepatitis a.

Hepatitis A virus is transmitted through ingestion of contaminated food or water or through direct contact with an infectious person. Hepatitis A is among the most common vaccine-preventable infections acquired during travel. Risk is greatest for people who live or visit rural areas, trek in backcountry areas, or frequently eat or drink in settings of poor sanitation. Vaccination is recommended for travelers to sub-Saharan Africa, including safari-goers (see Sec. 5, Part 2, Ch. 7, Hepatitis A ).

Travelers’ Diarrhea

Travelers’ diarrhea (TD) is the most predictable travel-related illness and is common on safaris. Prepare travelers by explaining the risks for TD and how best to prevent it through appropriate hand hygiene and careful selection of foods and beverages (see Sec. 2, Ch. 6, Travelers’ Diarrhea ). Infectious causes of TD include bacteria (e.g., Campylobacter jejuni , Escherichia coli , Salmonella spp., Shigella spp.), viruses (e.g., norovirus, rotavirus), and protozoa (e.g., Cryptosporidium , Giardia ).

Most TD cases are mild and self-limiting. Advise travelers to carry antimotility medicine for symptomatic relief of mild TD. Consider prescribing antibiotic therapy to treat moderate to severe TD and providing travelers with clear written guidance about TD prevention and step-by-step instructions about how and when to use medications. Travelers should carry any medications with them on safari, because access to authentic drugs is not guaranteed in remote locations (see Sec. 6, Ch. 3, . . . perspectives: Avoiding Poorly Regulated Medicines & Medical Products During Travel ). Travelers should consult a physician for moderate, severe, or persistent TD.

No vaccines are available for most pathogens that cause TD. Cholera vaccine is not needed for safari-goers unless they are planning a side trip to work in a refugee camp or do humanitarian aid work in an affected country. Advise travelers to carry alcohol-based hand sanitizer with ≥60% alcohol for use when water and soap are scarce or unsafe, or conditions are generally unhygienic. Travelers should avoid drinking tap water while on safari and only consume adequately disinfected (e.g., commercially bottled) water from an unopened, factory-sealed container (see Sec. 2, Ch. 8, Food & Water Precautions ).

Typhoid Fever

Typhoid fever is a bacterial disease caused by Salmonella typhi (see Sec. 5, Part 1, Ch. 24, Typhoid & Paratyphoid Fever ). Typhoid fever vaccine generally is recommended for safari-goers. Because vaccination does not confer 100% protection, however, even vaccinated travelers should avoid consumption of potentially contaminated food and water.

Respiratory Infections & Diseases

Respiratory illnesses (e.g., COVID-19, influenza, tuberculosis [TB]) can spread between people and from people to the wildlife they encounter.

Coronavirus Disease 2019

In zoos and animal sanctuaries, big cats (cougars, lions, pumas, tigers, snow leopards) and mountain gorillas have tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes COVID-19. Special operating procedures are in now place to protect wildlife and travelers; these include mandatory COVID-19 testing, limited group capacity, and required mask use to enter Volcanoes National Park and other gorilla parks; several game parks, including Kruger National Park in South Africa, also require entrants to provide a negative COVID-19 test result before permitting entry. Travelers should check with tour operators and park websites ahead of travel for up-to-date requirements, and follow park requirements to help keep both wildlife and people safe and healthy.

All travelers going to Africa should be up to date with their COVID-19 vaccines .

Influenza & Tuberculosis

While on safari, when trekking, or when visiting local communities, travelers can potentially encounter livestock species susceptible to influenza (e.g., chickens, pigs, waterfowl) and TB (e.g., cows).

Chimpanzees, gorillas, and other wildlife also are susceptible to influenza virus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Responsible tourism requires ill people to refrain from wildlife trekking or other activities that involve close contact with wildlife.

Soil- & Waterborne Infections

Schistosomiasis.

Freshwater lakes, ponds, and rivers all pose a risk for exposure to Schistosoma species, a parasite found in freshwater snails (see Sec. 5, Part 3, Ch. 20, Schistosomiasis ). Travelers should consider all freshwater sources to be contaminated and avoid bathing, swimming, wading, or other freshwater contact in disease-endemic countries. River trips (e.g., Nile River white-water rafting) present a risk for schistosomiasis (bilharzia). Swimming in the ocean or well-chlorinated pools is not a risk for schistosomiasis.

Vectorborne Diseases

Travelers should take steps to avoid arthropod bites to reduce their risk for vectorborne infections (for detailed recommendations, see Sec. 4, Ch. 6, Mosquitoes, Ticks & Other Arthropods ).

Chikungunya, Dengue, Zika

Chikungunya, dengue, and Zika are arboviruses transmitted by Aedes species mosquitoes in game parks throughout Africa (for details on each of these diseases, see the relevant chapters in Section 5). Aedes mosquitoes are aggressive daytime biters, but also bite at night.

Malaria is endemic in sub-Saharan Africa, and transmission occurs in most game parks. Most infections are caused by Plasmodium falciparum . All P. falciparum in sub-Saharan Africa is considered chloroquine-resistant. Safari activities often include sleeping in tents and observing animals at dusk or after dark, sometimes near water holes, all of which increase the risk for exposure to malaria-carrying Anopheles mosquitoes. Appropriate malaria chemoprophylaxis and personal protection—wearing long-sleeved shirts and pants, using insect repellents, and sleeping under permethrin-impregnated mosquito netting—are essential (see Sec. 2, Ch. 5, Yellow Fever Vaccine & Malaria Prevention Information, by Country , and Sec. 5, Part 3, Ch. 16, Malaria ).

Rickettsial Diseases

African tick-bite fever (ATBF) is endemic to much of sub-Saharan Africa; among returning travelers, it is the most commonly diagnosed rickettsial disease (see Sec. 5, Part 1, Ch. 18, Rickettsial Diseases ). Travel-associated cases of ATBF often occur in clusters of people exposed while participating in common activities (e.g., bush hiking, game hunting, safari tours). Travelers can protect themselves from infection by taking precautions to prevent tick bites.

Trypanosomiasis

Day-biting tsetse flies ( Glossina species) transmit African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness), a disease only rarely seen in travelers (see Sec. 5, Part 3, Ch. 24, African Trypanosomiasis ). Several reports document trypanosomiasis in travelers returning from visits to national parks or game reserves, including Kenya’s Maasai Mara National Reserve. Advise travelers that neutral-colored clothing seems to deter the flies, and that permethrin-impregnated clothing and insect repellant can reduce fly bites.

West Nile virus is an arbovirus transmitted by Culex species mosquitoes that are typically more active at dusk and dawn.

Yellow Fever

Travelers going on an African safari should consult a travel medicine professional for the very latest information regarding yellow fever at their destination. Currently, the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend yellow fever vaccination for much of sub-Saharan Africa (see Sec. 2, Ch. 5, Yellow Fever Vaccine & Malaria Prevention Information, by Country , and Sec. 5, Part 2, Ch. 26, Yellow Fever ).

Some countries require proof of yellow fever vaccination in the form of a valid International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis (ICVP), also known as the yellow card, as a condition of entry. Moreover, some safaris cross international borders to include ≥1 country. Assist travelers by checking the requirements for each country on their itinerary, including countries they only transit through on the way to their destination.

Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF), Ebola virus disease (EVD), Lassa fever, Marburg virus disease (MVD), and Rift Valley fever (RVF) are viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) found in and around some game parks in sub-Saharan Africa. Although travelers are rarely affected, zoonotic exposure to VHFs can occur through direct contact with wildlife (e.g., bats, nonhuman primates, rodents), insect (e.g., mosquito) or tick bites, and contact with blood or body fluid of livestock (see Sec. 5, Part 2, Ch. 25, Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers ).

Travelers who touch or come into proximity of bats (e.g., spelunking, visiting bat caves) are at greatest risk for Ebola virus or Marburg virus exposure. Four confirmed cases of MVD occurred in travelers visiting Kitum Cave in Kenya and Python Cave in Maramagambo Forest, Uganda. Caution travelers against visiting locations where VHF outbreaks are occurring, to avoid contact with bats and rodents, and to avoid blood or body fluids of livestock or animal carcasses.

Animal Bites & Wildlife-Related Injuries

Wild animals are unpredictable. Travelers should follow verbal and written instructions provided by safari operators and guides and should take extra precautions if camping or traveling without a guide in a national park. Wildlife-related injuries usually occur when travelers disregard rules (e.g., when they approach animals too closely to feed or photograph them). People should never try to feed, handle, or pet unfamiliar animals, whether domestic or wild. If bitten or scratched by a monkey, travelers should be evaluated for B virus postexposure prophylaxis (see Sec. 5, Part 2, Ch. 1, B Virus ).

Rabies exists throughout Africa; dogs and bats are the primary animal reservoirs (see Sec. 5, Part 2, Ch. 18, Rabies ). The estimated rate of rabies exposures in travelers ranges from 16–200 per 100,000 travelers globally. Warn travelers not to enter caves where bats roost and shelter. Advise travelers to consult a physician for rabies postexposure prophylaxis in case of animal bites or scratches or suspected bat exposures (e.g., sleeping in a cabin or tent where bats are found).

Consider preexposure prophylaxis for people whose planned activities will increase their chances of direct animal encounters (e.g., adventure travelers, animal sanctuary visitors, campers, cave explorers [spelunkers], participants in veterinary care or wildlife management programs). Additional considerations for preexposure prophylaxis might include whether rabies immunoglobulin (RIG) and rabies vaccination are available in the visited country in case of exposure.

Climate & Sun Exposure

Some parks are located at higher elevations and closer to the equator, making proper sun precautions imperative for avoiding sunburn, heat exhaustion, heat stroke, and dehydration. Advise travelers to seek shade, when possible, to avoid the sun during midday hours, and to carry water. In addition, advise travelers to wear sunglasses, protective clothing, and hats, and to use a broad-spectrum (protects against both ultraviolet A and ultraviolet B) sunscreen, SPF ≥15. Recommend travelers bring sunscreen and sunburn remedies with them, because selection can be limited and expensive once in country (see Sec. 4, Ch. 1, Sun Exposure ).

Natural Disasters

Natural disasters (e.g., earthquakes, flooding, landslides, volcanic eruptions) have all occurred and affected international travelers in recent years. During the rainy season, floods and landslides can be more common. Safari-goers should expect sudden road closures, plan alternative routes, and take precautions during storms. Dust storms might occur during the dry season. Poor air quality can exacerbate asthma or other lung diseases. Encourage all travelers to enroll in the US Department of State’s Smart Traveler Enrollment Program to receive up-to-date information in the event of a disaster.

Within the game parks, crime is unusual; robberies and car-jackings are more common in urban areas (see Sec. 4, Ch. 11, Safety & Security Overseas ). Travelers should check with the US Department of State’s Bureau of Consular Affairs ahead of travel to learn more about safety and security risks before traveling.

Traffic-Related Injuries

In sub-Saharan African countries, the rates of fatal motor vehicle crashes are among the highest in the world. Travelers should fasten seat belts when riding in motor vehicles, and wear a helmet when riding bicycles or motorbikes (see Sec. 8, Ch. 5, Road & Traffic Safety ). Within game parks, serious motor vehicle crashes are rare because poor road conditions generally discourage speeding. Travel in rural areas between parks is high risk, however, especially after dark. If possible, travelers should avoid nighttime driving in sub-Saharan Africa, and pedestrians should take extra care to watch for speeding vehicles. Travelers should avoid boarding overcrowded buses, and avoid driving or riding on motorcycles and motorbikes.

Travelers should work with their primary care provider to ensure any underlying illnesses are managed before travel. Before leaving the United States, each traveler also should be certain they have international health insurance coverage; and because surgical support or other advanced health care might not be available in the destination country, encourage travelers to purchase an additional medical evacuation insurance policy (see Sec. 6, Ch. 1, Travel Insurance, Travel Health Insurance & Medical Evacuation Insurance , and Sec. 6, Ch. 2, Obtaining Health Care Abroad ).

Recommend travelers carry a personal medical kit with sufficient medication to treat allergies, chronic conditions, routine health needs, and emergencies (see Sec. 2, Ch. 10, Travel Health Kits ). Warn travelers with food allergies that food labels might not reliably indicate potential allergens, and that lack of emergency services and language barriers can compound the risk for any severe allergic reaction that requires emergency medical care (see Sec. 3, Ch. 4, Highly Allergic Travelers ). Prescribe an epinephrine autoinjector for highly allergic travelers. Options for feminine hygiene products can be limited on safari—advise travelers to pack an adequate supply.

Symptoms of many diseases acquired in Africa can surface weeks and occasionally months after exposure, sometimes long after the traveler has returned home. Obtain a travel history from all patients presenting for care.

The following authors contributed to the previous version of this chapter: Karl Neumann

Bibliography

Angelo KM, Libman M, Caumes E, Hamer DH, Kain KC, Leder K, et al. Malaria after international travel: a GeoSentinel analysis, 2003–2016. Malar J. 2017;16(1):293.

Clerinx J, Van Gompel A. Schistosomiasis in travellers and migrants. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2011;9(1):6–24.

Cornel AJ, Lee Y, Almeida A, Johnson T, Mouatcho J, Ventner M, et al. Mosquito community composition in South Africa and some neighboring countries. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11(1):331.

Jensenius M, Fournier P, Kelly P, Myrvang B, Racoult D. African tick bite fever. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3(9):557–64.

Kading RC, Borland EM, Cranfield M, Powers AM. Prevalence of antibodies to alphaviruses and flaviviruses in free-ranging game animals and nonhuman primates in the greater Congo Basin. J Wildl Dis. 2013;49(3):587–99.

Lankau EW, Montgomery JM, Tack DM, Obonyo M, Kadivane S, Blanton JD, et al. Exposure of US travelers to rabid zebra, Kenya, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18(7):1202–4.

Macfie EJ, Williamson EA. Best practice guidelines for great ape tourism. Gland, Switzerland: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, Species Survival Commissioner Primate Specialist Group (PSG); 2010. Available from: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/ssc-op-038.pdf .

Makhulu EE, Villinger J, Adunga VO, Jeneby MM, Kimathi EM, Mararo E, et al. Tsetse blood-meal sources, endosymbionts and trypanosome-associations in the Maasai Mara National Reserve, a wildlife-human-livestock interface. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(1):e0008267.

Morgan OW, Brunette G, Kapella BK, McAuliffe I, Katongole-Mbidde E, Li W, et al. Schistosomiasis among recreational users of upper Nile River, Uganda, 2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;(16)5:866–8.

World Health Organization. Vaccines and vaccination against yellow fever. WHO position paper—June 2013. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2013;88(27):269–83.

File Formats Help:

- Adobe PDF file

- Microsoft PowerPoint file

- Microsoft Word file

- Microsoft Excel file

- Audio/Video file

- Apple Quicktime file

- RealPlayer file

- Zip Archive file

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Update April 12, 2024

Information for u.s. citizens in the middle east.

- Travel Advisories |

- Contact Us |

- MyTravelGov |

Find U.S. Embassies & Consulates

Travel.state.gov, congressional liaison, special issuance agency, u.s. passports, international travel, intercountry adoption, international parental child abduction, records and authentications, popular links, travel advisories, mytravelgov, stay connected, legal resources, legal information, info for u.s. law enforcement, replace or certify documents.

Share this page:

Kenya Travel Advisory

Travel advisory july 31, 2023, kenya - level 2: exercise increased caution.

Reissued with obsolete COVID-19 page links removed.

Exercise increased caution in Kenya due to crime, terrorism, civil unrest, and kidnapping . Some areas have increased risk. Read the entire Travel Advisory.

Do Not Travel to: Kenya-Somalia border counties and some coastal areas, due to terrorism and kidnapping .

Areas of Turkana County, due to crime .

Reconsider Travel to: Nairobi neighborhoods of Eastleigh and Kibera, due to crime and kidnapping .

Certain areas of Laikipia County, due to criminal incursions and security operations , reconsider travel through Nyahururu, Laikipia West, and Laikipia North Sub-counties.

Country Summary : Violent crime, such as armed carjacking, mugging, home invasion, and kidnapping, can occur at any time. Local police often lack the capability to respond effectively to serious criminal incidents and terrorist attacks. Emergency medical and fire service is also limited. Be especially careful when traveling after dark anywhere in Kenya due to crime.

Terrorist attacks have occurred with little or no warning, targeting Kenyan and foreign government facilities, tourist locations, transportation hubs, hotels, resorts, markets/shopping malls, and places of worship. Terrorist acts have included armed assaults, suicide operations, bomb/grenade attacks, and kidnappings.

Demonstrations may occur, blocking key intersections and resulting in widespread traffic jams. Strikes and other protest activity related to political and economic conditions occur regularly, particularly in periods near elections. Violence associated with demonstrations, ranging from rock throwing to police using deadly force, occurs around the country; it is mostly notable in western Kenya and Nairobi.

Due to risks to civil aviation operating in the vicinity of the Kenyan-Somali border, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has issued a Notice to Air Missions (NOTAM). For more information, U.S. citizens should consult Federal Aviation Administration’s Prohibitions, Restrictions, and Notice .

Some schools and other facilities acting as cultural rehabilitation centers are operating in Kenya with inadequate or nonexistent licensing and oversight. Reports of minors and young adults being held in these facilities against their will and physically abused are common.

Read the country information page for additional information about travel to Kenya.

If you decide to travel to Kenya:

- Stay alert in locations frequented by Westerners.

- Do not physically resist any robbery attempt.

- Monitor local media for breaking events and be prepared to adjust your plans.

- Make contingency plans to leave the country. in case of an emergency Review the Traveler’s Checklist ..

- Always carry a copy of your U.S. passport and visa (if applicable). Keep original documents in a secure location.

- Enroll in the Smart Traveler Enrollment Program (STEP) to receive security messages and make it easier to locate you in an emergency.

- Follow the Department of State on Facebook and Twitter .

- Review the Country Security Report for Kenya.

- Visit the CDC page for the latest Travel Health Information related to your travel.

Specified Areas - Level 4: Do Not Travel U.S. government personnel are prohibited from traveling to the below areas.

Kenya-Somalia Border Counties:

- Mandera due to kidnapping and terrorism.

- Wajir due to kidnapping and terrorism.

- Garissa due to kidnapping and terrorism.

Coastal Areas:

- Tana River county due to kidnapping and terrorism.

- Lamu county due to kidnapping and terrorism.

- Areas of Kilifi County north of Malindi due to kidnapping and terrorism.

Turkana County:

- Road from Kainuk to Lodwar due to crime and armed robbery, which occur frequently.

Specified Areas - Level 3: Reconsider Travel

Nairobi neighborhoods of Eastleigh and Kibera:

- Violent crime, such as armed carjacking, mugging, home invasion, and kidnapping, can occur at any time. Street crime can involve multiple armed assailants. Local police often lack the resources and training to respond effectively to serious criminal incidents.

Laikipia County:

- Certain areas of Laikipia County, due to criminal incursions and security operations, reconsider travel through Nyahururu, Laikipia West, and Laikipia North Sub-counties.

Consider carefully whether to use the Likoni ferry in Mombasa due to safety concerns.

Visit our website for Travel to High-Risk Areas.

Travel Advisory Levels

Assistance for u.s. citizens, search for travel advisories, external link.

You are about to leave travel.state.gov for an external website that is not maintained by the U.S. Department of State.

Links to external websites are provided as a convenience and should not be construed as an endorsement by the U.S. Department of State of the views or products contained therein. If you wish to remain on travel.state.gov, click the "cancel" message.

You are about to visit:

Exclusive: U.S. to lift travel curbs on eight African countries

- Medium Text

The Reuters Daily Briefing newsletter provides all the news you need to start your day. Sign up here.

Reporting by David Shepardson in Grand Rapids, Michigan; Editing by Nick Macfie

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. New Tab , opens new tab

World Chevron

X vows to 'robustly challenge' Australia order to remove stabbing posts

Social media platform X said on Saturday it would challenge in court an order from an Australian regulator demanding the company remove some posts related to the stabbing of a bishop in Sydney.

Russian war correspondent Semyon Eremin, who worked for the Russian daily Izvestia, was killed on Friday in a Ukrainian drone attack in southeastern Ukraine, the newspaper said.

A Guide to Travel Restrictions Throughout Africa

By Sarah Khan

Many predicted dire consequences when COVID-19 made its way across Africa , but the case numbers in African countries have largely remained low, especially in contrast with the United State s and Europe .

Experts have posited that factors like climate, strict lockdown, the continent’s relatively young population (more than 60 percent of Africans are under 25), and preparation measures already in place for other outbreaks may have all played a role.

But case counts, as well as government responses, have varied across the continent. South Africa has been the continent’s worst-affected country, accounting for nearly half the deaths despite a rather strict lockdown, and now a new, more infectious variant ; Rwanda, which has also implemented strict measures, has reported just over 200 deaths; while Tanzania stopped releasing official numbers after April and resumed international travel early, with surprisingly relaxed measures.

Many African nations are welcoming foreign travelers again, but quite a few exclude visitors from America. On the flip side, the United States has recently added South Africa to its COVID travel restrictions, meaning that non-U.S. citizens (including residents), may not enter the country if they were in South Africa within the 14 days prior. If you do decide to travel, be conscientious about not overburdening the local health systems. Stay on top of each country’s rules—which are subject to change based on rising case numbers—and wear masks , practice social distancing, and sanitize regularly.

Northern Africa

As of July, Egypt has been open to international travelers. All visitors must present printed results from a negative PCR test taken within 96 hours of entry, and must fill out a Public Health Card for contact tracing on arrival. Anyone flying directly into Hurghada, Sharm El Sheikh, Marsa Alam, or Taba who doesn’t have a PCR test must test on arrival and stay in their hotel room until the results are available. All indoor events are canceled, and restaurants and cafes are operating at 50 percent capacity.

Though Morocco began lifting travel restrictions in September, the country is under a new state of emergency, with a nationwide curfew.

Morocco , which began lifting restrictions in September, has since instated a Health State of Emergency until February 10 at the earliest and implemented a nationwide curfew. Under that, restaurants, cafes, shops, and supermarkets throughout the country close at 8 p.m.

Travelers from visa-exempt countries—including the U.S.—with confirmed hotel reservations are allowed, as are business travelers invited by Moroccan companies. Visitors must have a negative PCR test taken less than 72 hours before departure, with printed results to be presented at check in and health screenings at the port of entry. The rules change frequently and can make travel within Morocco a challenge.

East Africa

One of the first African countries to open widely for tourism, back in June, was Tanzania . At the time, there were no testing or quarantine requirements. That was changed in August to require a negative PCR test taken within 72 hours of travel, but the rule was later lifted in September. Now only enhanced screenings (and testing on arrival, if deemed necessary) are required. That said, your airline will likely require a negative PCR test to board, so it’s best to get tested regardless of changing rules. Keep in mind that the Tanzanian government has not released any of its COVID-19 statistics since April, so accurate information about the impact of the pandemic on locals is not readily available. The U.S. has also given the destination a Level 4 travel warning , saying “travelers should avoid all travel to Tanzania” due to a “very high level of COVID-19.”

Tanzania was one of the first African countries to reopen for tourism, though the U.S. government warns travelers against visiting right now.

Kenya reopened its borders to international travelers—Americans included—in August. As of February, all travelers must present a digitally verified COVID test through the Trusted Traveler program . Group gatherings are banned throughout the country, with the exception of funerals and weddings, which are allowed to host up to 150 people .

Anna Borges

Jessica Puckett

Karthika Gupta

Rwanda is open to travelers, but you'll have to jump through some hoops before you can go gorilla trekking . First, fill out Rwanda’s passenger locator form online —you’ll have to upload a negative PCR test taken less than 120 hours before departure, along with your hotel reservation. A second PCR test is administered upon arrival in Kigali (at a cost of $50, plus a $10 medical services fee), and you’ll quarantine in your hotel room at your own expense until the results come back within 24 hours. To enter Volcanoes , Nyungwe , or Akagera national parks, you’ll have to submit a registration and indemnity form prior to arrival (ask your local tour operator for this), and also test negative within 72 hours of your park visit. Travelers must test negative once again before departure.

Uganda reopened borders October 1 with new safety measures: a negative PCR test issued within 120 hours of travel is required. Officials recommend arriving at the airport four hours prior to your flight to clear all medical screenings. In addition to regulated social distancing around other people, visitors to Uganda’s national parks must stay at least 32 feet away from gorillas during sightings.

Visitors to Ethiopia can fly into Addis Ababa Bole International Airport’s brand-new $300 million contactless, biosafety-focused airport terminal —but to do so, you’ll need to present a negative PCR test taken within five days of arrival in Ethiopia. Even with the negative test, all visitors must self-isolate at a hotel for seven days.

Indian Ocean islands

Seychelles has been slowly reopening to international travel, but Americans have not yet made the cut—except for those who are fully vaccinated. Anyone who’s received both doses of the vaccination is welcome from anywhere in the world, provided they show proof of vaccination and they’re traveling more than two weeks after their second dose. A negative PCR test within 72 hours is still required. The country projects that the majority of Seychelles’ adults will be vaccinated by mid-March, which is when they plan to open fully for international tourism.

Southern Africa

South Africa recorded the highest number of COVID-19 cases in Africa—more than half of the total numbers on the continent. The country began reopening its borders to Americans in November, requiring a negative PCR test taken within 72 hours of arrival and the use of a COVID tracing app. Travelers must also fill out a health questionnaire two days prior to arriving and two days prior to departing. The emergence of a new variant in recent weeks has caused concerns. Last week, Biden added South Africa to a list of restricted countries (though U.S. citizens can return from South Africa), and there’s now a national lockdown in place from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m.

U.S. citizens will be permitted enter Zambia upon presenting a negative PCR test result taken within seven days of departure. You can apply for an e-visa online . Travelers to Zimbabwe must present a negative COVID-19 PCR test taken within 48 hours of departure, but should be aware that a new, strict lockdown began this month, which prohibits all gatherings, the closure of non-essential businesses, and a 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. curfew. For Namibia , a negative PCR test taken 72 hours before arrival is required; if your test was taken more than 72 hours but less than one week before arrival, you’ll have to undergo supervised isolation at a government-approved hotel for seven days.

West Africa

Arriving in Ghana is a two-test process: First, you need a negative PCR test result from within 72 hours of departure in hand; then, you'll head to a new state-of-the-art lab that has been set up at Accra’s Kotoka International Airport for mandatory antigen tests at each travelers’ own expense ($150). Results typically arrive within 15 minutes, though the test must be paid for online in advance.

Nigeria reopened in September with strict testing protocols. Travelers must upload proof of a negative PCR test taken within 96 hours before boarding their flight to receive a QR code with a Permit to Travel certificate; both this and the negative PCR test must be shown in order to board any flight to Nigeria, and then again on arrival. After seven days, a second PCR test must be taken at the traveler's expense (ranging from about $112 to $132). Before traveling to Nigeria, visit the country’s travel portal to fill out a health questionnaire, upload your first negative PCR test result, and schedule and pay in advance for your second test.

All travelers to Senegal must present a negative PCR test dated within five days of arrival, as well as submit a passenger locator form . While some public spaces, like bars and theaters, remain closed, restaurants, private beaches, and markets are partially open with social distancing measures in effect, and a nightly curfew from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m.

This article was originally published in November 2020. It has been updated with new information. We’re reporting on how COVID-19 impacts travel on a daily basis. Find our latest coronavirus coverage here , or visit our complete guide to COVID-19 and travel .

Recommended

Royal Mansour Casablanca: First Guest

andBeyond Phinda Forest Lodge: First In

Africa Travel Guide

By signing up you agree to our User Agreement (including the class action waiver and arbitration provisions ), our Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement and to receive marketing and account-related emails from Traveller. You can unsubscribe at any time. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

- Quick Links

- Make An Appointment

- Our Services

- Price Estimate

- Price Transparency

- Pay Your Bill

- Patient Experience

- Careers at UH

Schedule an appointment today

Kenya Travel Requirements & Vaccinations

Kenya is a country on the east coast of Africa. Officially known as the Republic of Kenya, it is named for Mount Kenya, the second-highest peak on the continent at 17,057 feet. Swahili and English are the two official languages of Kenya.

The landscape in Kenya is diverse, ranging from low plains and highlands to plateaus and valleys. The climate varies depending on location with tropical conditions prevailing along the coastline and dry, desert-like heat in the northern parts of the country. Daytime temperatures are warm year-round with significant cooling at night, especially inland and at higher elevations. The hottest months are February and March and the coolest are July and August. There are two rainy seasons in Kenya which occur from March to June, and then again from October to December. The rainfall can be heavy so travelers should be prepared if visiting the country during these months.

Kenya offers a vast selection of attractions and sightseeing opportunities, including:

- Safaris through national parks and game reserves

- The Serengeti Migration of the wildebeest, which is listed among the seven natural wonders of Africa

- Historical mosques and colonial-era forts

- Tea and coffee plantations

- Beaches along the Swahili Coast of the Indian Ocean

- Diverse populations of wildlife, reptiles and birds

Recommended Vaccinations for Travel to Kenya

- Hepatitis A

- Malaria (pill form)

- Yellow Fever

*Rabies vaccination is typically only recommended for very high risk travelers given that it is completely preventable if medical attention is received within 7 – 10 days of an animal bite.

Travelers may also be advised to ensure they have received the routine vaccinations listed below. Some adults may need to receive a booster for some of these diseases:

- Measles, mumps and rubella (MMR)

- Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis)

Older adults or those with certain medical conditions may also want to ask about being vaccinated for shingles and/or pneumonia.

This information is not intended to replace the advice of a travel medicine professional. Not all of the vaccines listed here will be necessary for every individual.

Talk to the experts at UH Roe Green Center for Travel Medicine & Global Health to determine how each member of your family can obtain maximum protection against illness, disease and injury while traveling, based on age, health, medical history and travel itinerary.

Malaria Information and Prophylaxis, by Country [A]

The information presented in this table is consistent 1 with the information in the CDC Health Information for International Travel (the “Yellow Book”).

1. Factors that affect local malaria transmission patterns can change rapidly and from year to year, such as local weather conditions, mosquito vector density, and prevalence of infection. Information in these tables is updated regularly. 2. Refers to P. falciparum malaria unless otherwise noted. 3. Estimates of malaria species are based on best available data from multiple sources. Where proportions are not available, the primary species and less common species are identified. 4. Several medications are available for chemoprophylaxis . When deciding which drug to use, consider specific itinerary, length of trip, cost of drug, previous adverse reactions to antimalarials, drug allergies, and current medical history. All travelers should seek medical attention in the event of fever during or after return from travel to areas with malaria. 5. Primaquine and tafenoquine can cause hemolytic anemia in persons with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. Before prescribing primaquine or tafenoquine, patients must be screened for G6PD deficiency using a quantitative test. 6. Mosquito avoidance includes applying topical mosquito repellant, sleeping under an insecticide treated bed net, and wearing protective clothing (e.g., long pants and socks, long sleeve shirt). For additional details on mosquito avoidance, see: https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/travelers/index.html 7. P. knowlesi is a malaria species with a simian host (macaque). Human cases have been reported from most countries in Southeast Asia and are associated with activities in forest or forest-fringe areas. This species of malaria has no known resistance to antimalarials.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

NICHOLAS A. RATHJEN, DO, AND S. DAVID SHAHBODAGHI, MD, MPH

Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(4):396-403

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Approximately 1.8 billion people will cross an international border by 2030, and 66% of travelers will develop a travel-related illness. Most travel-related illnesses are self-limiting and do not require significant intervention; others could cause significant morbidity or mortality. Physicians should begin with a thorough history and clinical examination to have the highest probability of making the correct diagnosis. Targeted questioning should focus on the type of trip taken, the travel itinerary, and a list of all geographic locations visited. Inquiries should also be made about pretravel preparations, such as chemoprophylactic medications, vaccinations, and any personal protective measures such as insect repellents or specialized clothing. Travelers visiting friends and relatives are at a higher risk of travel-related illnesses and more severe infections. The two most common vaccine-preventable illnesses in travelers are influenza and hepatitis A. Most travel-related illnesses become apparent soon after arriving at home because incubation periods are rarely longer than four to six weeks. The most common illnesses in travelers from resource-rich to resource-poor locations are travelers diarrhea and respiratory infections. Localizing symptoms such as fever with respiratory, gastrointestinal, or skin-related concerns may aid in identifying the underlying etiology.

Globally, it is estimated that 1.8 billion people will cross an international border by 2030. 1 Although Europe is the most common destination, tourism is increasing in developing regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. 2 Less than one-half of U.S. travelers seek pretravel medical advice. It is estimated that two-thirds of travelers will develop a travel-related illness; therefore, the ill returning traveler is not uncommon in primary care. 3 Although most of these illnesses are minor and relatively insignificant clinically, the potential exists for serious illness. The advent of modern and interconnected travel networks means that a rare illness or nonendemic infectious disease is never more than 24 hours away. 4 Travelers over the past 10 years have contributed to the increase of emerging infectious diseases such as chikungunya, Zika virus infection, COVID-19, mpox (monkeypox), and Ebola disease. 3

Although most travel-related illnesses are self-limiting and do not require medical evaluation, others could be life-threatening. 5 The challenge for the busy physician is successfully differentiating between the two. Physicians should begin with a thorough history and clinical examination to have the highest probability of making the correct diagnosis. Travelers at the highest risk are those visiting friends and relatives who stay in a country for more than 28 days or travel to Africa. Most travel-related illnesses become apparent soon after arriving home because incubation periods are rarely longer than four to six weeks. 3 , 6 The most common illnesses in travelers from resource-rich to resource-poor locations are travelers diarrhea and respiratory infections. 7 , 8 The incubation period of an illness relative to the onset of symptoms and the length of stay in the foreign destination can exclude infections in the differential diagnosis ( eTable A ) .

General questions should determine the patient’s pertinent medical history, focusing on any unique factors, such as immunocompromising illnesses or underlying risk factors for a travel-related medical concern. Targeted questioning should focus on the type of trip taken and the travel itinerary that includes accommodations, recreational activities, and a list of all geographic locations visited ( Table 1 3 , 6 , 9 and Table 2 3 , 6 ) . Patients should be asked about any medical treatments received in a foreign country. Modern travel itineraries often require multiple stopovers, and it is not uncommon for the casual traveler to visit several locations with different geographically linked illness patterns in a single trip abroad.

Travel History

Travelers visiting friends and relatives are at a higher risk of travel-related illnesses and more severe infections. 10 , 11 These travelers rarely seek pretravel consultation, are less likely to take chemoprophylaxis, and engage in more risky travel-related behaviors such as consuming food from local sources and traveling to more remote locations. 3 Overall, travelers visiting friends and relatives tend to have extended travel stays and are more likely to reside in non–climate-controlled dwellings.

During the clinical history, inquiries should be made about pretravel preparations, including chemoprophylactic medications, vaccinations, and personal protective measures such as insect repellents or specialized clothing. 12 , 13 Accurate knowledge of previous preventive strategies allows for appropriate risk stratification by physicians. Even when used thoroughly, these measures decrease the likelihood of certain illnesses but do not exclude them. 6 Adherence to dietary precautions and pretravel immunization against typhoid fever do not necessarily eliminate the risk of disease. Travelers often have no control over meals prepared in foreign food establishments, and the currently available typhoid vaccines are 60% to 80% effective. 14 Although all travel-related vaccines are important, the two most common vaccine-preventable illnesses in travelers are influenza and hepatitis A. 12 , 15

Travel duration is also an important but often overlooked component of the clinical history because the likelihood of illness increases directly with the length of stay abroad. The longer travelers stay in a non-native environment, the more likely they are to forego travel precautions and adherence to chemoprophylaxis. 3 The use of personal protective measures decreases gradually with the total amount of time in the host environment. 3 A thorough medical and sexual history should be obtained because data show that sexual contact during travel is common and often occurs without the use of barrier contraception. 16

Clinical Assessment

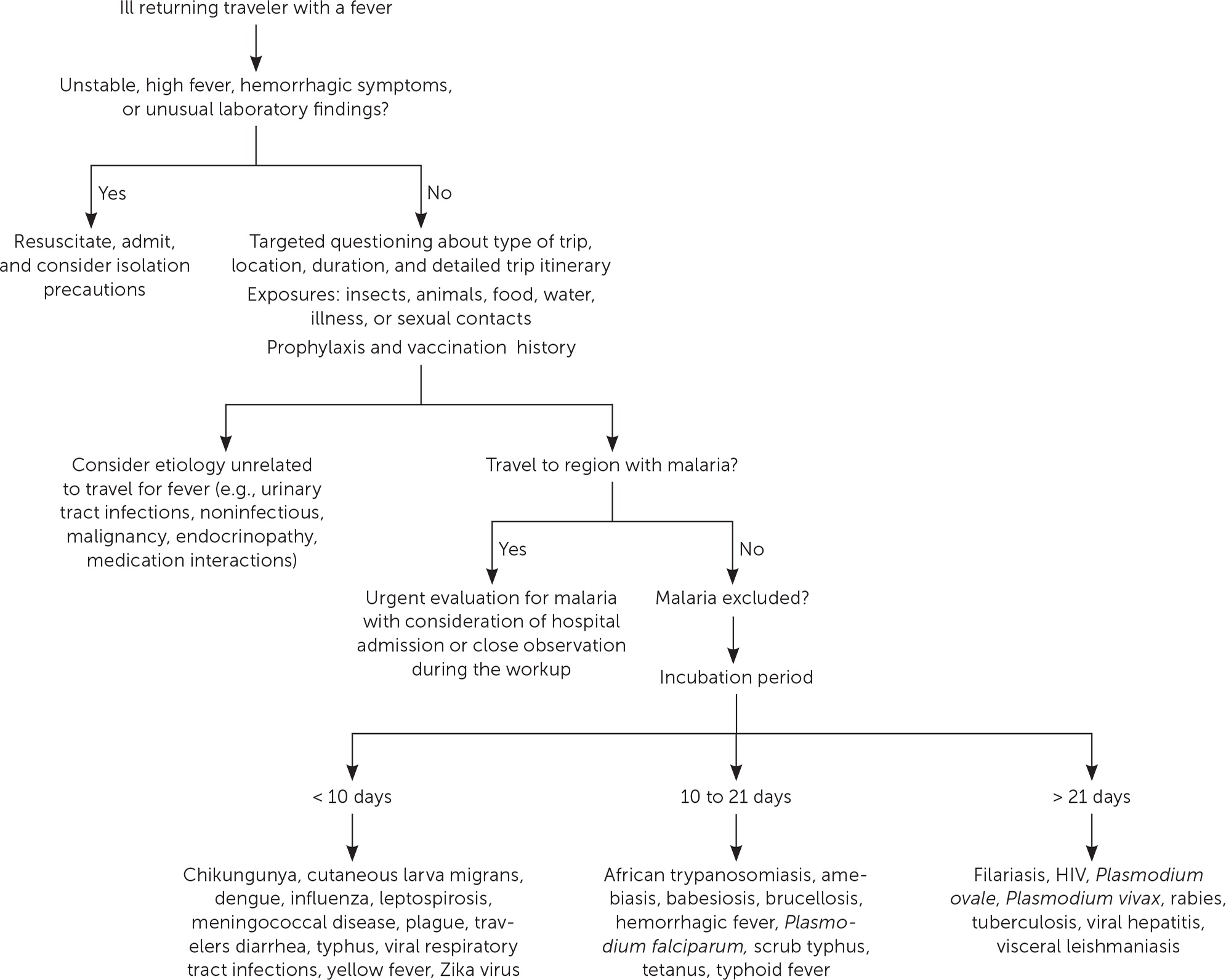

The severity of the illness helps determine if the patient should be admitted to the hospital while the evaluation is in progress. 3 Patients with high fevers, hemorrhagic symptoms, or abnormal laboratory findings should be hospitalized or placed in isolation ( Figure 1 ) . For patients with a higher severity of illness, consultation with an infectious disease or tropical/travel medicine physician is advised. 3 Patients with symptoms that suggest acute malaria (e.g., fever, altered mental status, chills, headaches, myalgias, malaise) should be admitted for observation while the evaluation is expeditiously completed. 13

Many tools can assist physicians in making an accurate diagnosis. The GeoSentinel is a worldwide data collection network for the surveillance and research of travel-related illnesses; however, this service requires a subscription. The network can guide physicians to the most likely illness based on geographic location and top diagnoses by geography. 4 For example, Plasmodium falciparum malaria is the most common serious febrile illness in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa. 17

Ill returning travelers should have a laboratory evaluation performed with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and C-reactive protein. Additional testing may include blood-based rapid molecular assays for malaria and arboviruses; blood, stool, and urine cultures; and thick and thin blood smears for malaria. 3 Emerging polymerase chain reaction technologies are becoming widely available across the United States. Multiplex and biofilm array polymerase chain reaction platforms for bacterial, viral, and protozoal pathogens are now available at most tertiary health care centers. 4 Multiplex and biofilm platforms include dedicated panels for respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses and bloodborne pathogens. These tests allow for real-time or near real-time diagnosis of agents that were previously difficult to isolate outside of the reference laboratory setting.

Table 3 lists common tropical diseases and associated vectors. 3 , 6 , 18 Physicians should be aware of unique and emerging infections, such as viral hemorrhagic fevers, COVID-19, and novel respiratory pathogens, in addition to common illnesses. Testing for infections of public health importance can be performed with assistance from local public health authorities. 19 In cases of short-term travel, previously acquired non–travel-related conditions should be on any list of applicable differential diagnoses. References on infectious diseases endemic in many geographic locations are accessible online. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Travelers’ Health website provides free resources for patients and health care professionals at https://www.cdc.gov/travel .

Febrile Illness

A fever typically accompanies serious illnesses in returning travelers. Patients with a fever should be treated as moderately ill. One barrier to an accurate and early diagnosis of travel-related infections is the nonspecific nature of the initial symptoms of illness. Often, these symptoms are vague and nonfocal. A febrile illness with a fever as the primary presenting symptom could represent a viral upper respiratory tract infection, acute influenza, or even malaria, typhoid, or dengue, which are the most life-threatening. According to GeoSentinel data, 91% of ill returning travelers with an acute, life-threatening illness present with a fever. 20 All travelers who are febrile and have recently returned from a malarious area should be urgently evaluated for the disease. 13 , 21 Travelers who have symptoms of malaria should seek medical attention, regardless of whether prophylaxis or preventive measures were used. Suspicion of P. falciparum malaria is a medical emergency. 13 Clinical deterioration or death can occur in a malaria-naive patient within 24 to 36 hours. 22 Dengue is an important cause of fever in travelers returning from tropical locations. An estimated 50 million to 100 million global cases of dengue are reported annually, with many more going undetected. 23 eTable B lists the most common causes of fever in the returning traveler.

Respiratory Illness

Respiratory infections are common in the United States and throughout the world. Ill returning travelers with respiratory concerns are statistically most likely to have a viral respiratory tract infection. 24 Influenza circulates year-round in tropical climates and is one of the most common vaccine-preventable illnesses in travelers. 3 , 12 Influenza A and B frequently present with a low-grade fever, cough, congestion, myalgia, and malaise. eTable C lists the most common causes of respiratory illnesses in the returning traveler.

Gastrointestinal Illness

Gastrointestinal symptoms account for approximately one-third of returning travelers who seek medical attention. 25 Most diarrhea in travelers is self-limiting, with travelers diarrhea being the most common travel-related illness. 7 Diarrhea linked to travel in resource-poor areas is usually caused by bacterial, viral, or protozoal pathogens.

The most often encountered diarrheal pathogens are enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and enteroaggregative E. coli , which are easily treated with commonly available antibiotics. 26 Physicians should be aware of emerging antibiotic resistance patterns across the globe. The CDC offers up-to-date travel information in the CDC Yellow Book . 3 Although patients are often concerned about parasites, they should be reassured that helminths and other parasitic infections are rare in the casual traveler. 3

The disease of concern in the setting of gastrointestinal symptoms is typhoid fever. Physicians should be aware that typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever are clinically indistinguishable, with cardinal symptoms of fever and abdominal pain. 3 Typhoid fever should be considered in ill returning travelers who do not have diarrhea, because typhoid infection may not present with diarrheal symptoms. The likelihood of typhoid fever also correlates with travel to endemic regions and should be considered an alternative diagnosis in patients not responding to antimalarial medications. A diagnosis of enteric fever can be confirmed with blood or stool cultures. Although less common, community-acquired Clostridioides difficile should be considered in the differential diagnosis in the setting of recent travel and potential antimicrobial use abroad. 27

Another important travel-related pathogen is hepatitis A due to its widespread distribution in the developing world and the small pathogen dose necessary to cause illness. Hepatitis A is a more serious infection in adults; however, many U.S. adults have been vaccinated because the hepatitis A vaccine is included in the recommended childhood immunization schedule. 28 eTable D lists the most common causes of gastrointestinal illnesses in the returning traveler.

Dermatologic Concerns

Dermatologic concerns are common among returning travelers and include noninfectious causes such as sun overexposure, contact with new or unfamiliar hygiene products, and insect bites. The most common infections in returning travelers with dermatologic concerns include cutaneous larva migrans, infected insect bites, and skin abscesses. Cutaneous larva migrans typically presents with an intensely pruritic serpiginous rash on the feet or gluteal region. 3 Questions about bites and bite avoidance measures should be asked of patients with symptomatic skin concerns; however, physicians should remember that many bites go unnoticed. 29

Formerly common illnesses in the United States are common abroad, with measles, varicella-zoster virus infection, and rubella occurring in child and adult travelers. 3 Measles is considered one of the most contagious infectious diseases. More than one-third of child travelers from the United States have not completed the recommended course of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines at the time of travel due to immunization scheduling. One-half of all measles importations into the United States comes from these international travelers. 30 Measles should always be considered in the differential because of the low or incomplete vaccination rates in travelers and high levels of exposure in some areas abroad. eTable E lists the most common infectious causes of dermatologic concern in the returning traveler.

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key words prevention, diagnosis, treatment, travel related illness, surveillance, travel medicine, chemoprophylaxis, and returning traveler treatment. The search was limited to English-language studies published since 2000. Secondary references from the key articles identified by the search were used as well. Also searched were the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Cochrane databases. Search dates: September 2022 to November 2022, March 2023, and August 2023.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

The World Tourism Organization. International tourists to hit 1.8 billion by 2030. October 11, 2011. Accessed March 2023. https://www.unwto.org/archive/global/press-release/2011-10-11/international-tourists-hit-18-billion-2030

- Angelo KM, Kozarsky PE, Ryan ET, et al. What proportion of international travellers acquire a travel-related illness? A review of the literature. J Travel Med. 2017;24(5):10.1093/jtm/tax046.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Yellow Book: Health Information for International Travel . Oxford University Press; 2023. Accessed August 26, 2023. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2024/table-of-contents

Wu HM. Evaluation of the sick returned traveler. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2019;36(3):197-202.

Scaggs Huang FA, Schlaudecker E. Fever in the returning traveler. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2018;32(1):163-188.

Feder HM, Mansilla-Rivera K. Fever in returning travelers: a case-based approach. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88(8):524-530.

Giddings SL, Stevens AM, Leung DT. Traveler's diarrhea. Med Clin North Am. 2016;100(2):317-330.

Harvey K, Esposito DH, Han P, et al.; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for travel-related disease–GeoSentinel Surveillance System, United States, 1997–2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:1-23.

Sridhar S, Turbett SE, Harris JB, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in international travelers. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2021;34(5):423-431.

Matteelli A, Carvalho AC, Bigoni S. Visiting relatives and friends (VFR), pregnant, and other vulnerable travelers. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26(3):625-635.

Ladhani S, Aibara RJ, Riordan FA, et al. Imported malaria in children: a review of clinical studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(5):349-357.

Sanford C, McConnell A, Osborn J. The pretravel consultation. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(8):620-627.

Shahbodaghi SD, Rathjen NA. Malaria. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(3):270-278.

Freedman DO, Chen LH, Kozarsky PE. Medical considerations before international travel. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):247-260.

- Marti F, Steffen R, Mutsch M. Influenza vaccine: a travelers' vaccine? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008;7(5):679-687.

Vivancos R, Abubakar I, Hunter PR. Foreign travel, casual sex, and sexually transmitted infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14(10):e842-e851.

Paquet D, Jung L, Trawinski H, et al. Fever in the returning traveler. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2022;119(22):400-407.

Cantey PT, Montgomery SP, Straily A. Neglected parasitic infections: what family physicians need to know—a CDC update. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(3):277-287.

Rathjen NA, Shahbodaghi SD. Bioterrorism. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(4):376-385.

Jensenius M, Davis X, von Sonnenburg F, et al.; Geo-Sentinel Surveillance Network. Multicenter GeoSentinel analysis of rickettsial diseases in international travelers, 1996–2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(11):1791-1798.

Tolle MA. Evaluating a sick child after travel to developing countries. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(6):704-713.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About malaria. February 2, 2022. Accessed August 21, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/index.html

Wilder-Smith A, Schwartz E. Dengue in travelers. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(9):924-932.

Summer A, Stauffer WM. Evaluation of the sick child following travel to the tropics. Pediatr Ann. 2008;37(12):821-826.

Swaminathan A, Torresi J, Schlagenhauf P, et al.; GeoSentinel Network. A global study of pathogens and host risk factors associated with infectious gastrointestinal disease in returned international travellers. J Infect. 2009;59(1):19-27.

Shah N, DuPont HL, Ramsey DJ. Global etiology of travelers' diarrhea: systematic review from 1973 to the present. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80(4):609-614.

Michal Stevens A, Esposito DH, Stoney RJ, et al.; GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clostridium difficile infection in returning travellers. J Travel Med. 2017;24(3):1-6.

Mayer CA, Neilson AA. Hepatitis A - prevention in travellers. Aust Fam Physician. 2010;39(12):924-928.

Herness J, Snyder MJ, Newman RS. Arthropod bites and stings. Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(2):137-147.

Bangs AC, Gastañaduy P, Neilan AM, et al. The clinical and economic impact of measles-mumps-rubella vaccinations to prevent measles importations from U.S. pediatric travelers returning from abroad. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2022;11(6):257-266.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2023 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What the data says about abortion in the U.S.

Pew Research Center has conducted many surveys about abortion over the years, providing a lens into Americans’ views on whether the procedure should be legal, among a host of other questions.

In a Center survey conducted nearly a year after the Supreme Court’s June 2022 decision that ended the constitutional right to abortion , 62% of U.S. adults said the practice should be legal in all or most cases, while 36% said it should be illegal in all or most cases. Another survey conducted a few months before the decision showed that relatively few Americans take an absolutist view on the issue .

Find answers to common questions about abortion in America, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, which have tracked these patterns for several decades:

How many abortions are there in the U.S. each year?

How has the number of abortions in the u.s. changed over time, what is the abortion rate among women in the u.s. how has it changed over time, what are the most common types of abortion, how many abortion providers are there in the u.s., and how has that number changed, what percentage of abortions are for women who live in a different state from the abortion provider, what are the demographics of women who have had abortions, when during pregnancy do most abortions occur, how often are there medical complications from abortion.

This compilation of data on abortion in the United States draws mainly from two sources: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Guttmacher Institute, both of which have regularly compiled national abortion data for approximately half a century, and which collect their data in different ways.

The CDC data that is highlighted in this post comes from the agency’s “abortion surveillance” reports, which have been published annually since 1974 (and which have included data from 1969). Its figures from 1973 through 1996 include data from all 50 states, the District of Columbia and New York City – 52 “reporting areas” in all. Since 1997, the CDC’s totals have lacked data from some states (most notably California) for the years that those states did not report data to the agency. The four reporting areas that did not submit data to the CDC in 2021 – California, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey – accounted for approximately 25% of all legal induced abortions in the U.S. in 2020, according to Guttmacher’s data. Most states, though, do have data in the reports, and the figures for the vast majority of them came from each state’s central health agency, while for some states, the figures came from hospitals and other medical facilities.

Discussion of CDC abortion data involving women’s state of residence, marital status, race, ethnicity, age, abortion history and the number of previous live births excludes the low share of abortions where that information was not supplied. Read the methodology for the CDC’s latest abortion surveillance report , which includes data from 2021, for more details. Previous reports can be found at stacks.cdc.gov by entering “abortion surveillance” into the search box.

For the numbers of deaths caused by induced abortions in 1963 and 1965, this analysis looks at reports by the then-U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare, a precursor to the Department of Health and Human Services. In computing those figures, we excluded abortions listed in the report under the categories “spontaneous or unspecified” or as “other.” (“Spontaneous abortion” is another way of referring to miscarriages.)

Guttmacher data in this post comes from national surveys of abortion providers that Guttmacher has conducted 19 times since 1973. Guttmacher compiles its figures after contacting every known provider of abortions – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, and it provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond to its inquiries. (In 2020, the last year for which it has released data on the number of abortions in the U.S., it used estimates for 12% of abortions.) For most of the 2000s, Guttmacher has conducted these national surveys every three years, each time getting abortion data for the prior two years. For each interim year, Guttmacher has calculated estimates based on trends from its own figures and from other data.

The latest full summary of Guttmacher data came in the institute’s report titled “Abortion Incidence and Service Availability in the United States, 2020.” It includes figures for 2020 and 2019 and estimates for 2018. The report includes a methods section.

In addition, this post uses data from StatPearls, an online health care resource, on complications from abortion.

An exact answer is hard to come by. The CDC and the Guttmacher Institute have each tried to measure this for around half a century, but they use different methods and publish different figures.

The last year for which the CDC reported a yearly national total for abortions is 2021. It found there were 625,978 abortions in the District of Columbia and the 46 states with available data that year, up from 597,355 in those states and D.C. in 2020. The corresponding figure for 2019 was 607,720.

The last year for which Guttmacher reported a yearly national total was 2020. It said there were 930,160 abortions that year in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, compared with 916,460 in 2019.

- How the CDC gets its data: It compiles figures that are voluntarily reported by states’ central health agencies, including separate figures for New York City and the District of Columbia. Its latest totals do not include figures from California, Maryland, New Hampshire or New Jersey, which did not report data to the CDC. ( Read the methodology from the latest CDC report .)

- How Guttmacher gets its data: It compiles its figures after contacting every known abortion provider – clinics, hospitals and physicians’ offices – in the country. It uses questionnaires and health department data, then provides estimates for abortion providers that don’t respond. Guttmacher’s figures are higher than the CDC’s in part because they include data (and in some instances, estimates) from all 50 states. ( Read the institute’s latest full report and methodology .)

While the Guttmacher Institute supports abortion rights, its empirical data on abortions in the U.S. has been widely cited by groups and publications across the political spectrum, including by a number of those that disagree with its positions .

These estimates from Guttmacher and the CDC are results of multiyear efforts to collect data on abortion across the U.S. Last year, Guttmacher also began publishing less precise estimates every few months , based on a much smaller sample of providers.

The figures reported by these organizations include only legal induced abortions conducted by clinics, hospitals or physicians’ offices, or those that make use of abortion pills dispensed from certified facilities such as clinics or physicians’ offices. They do not account for the use of abortion pills that were obtained outside of clinical settings .

(Back to top)

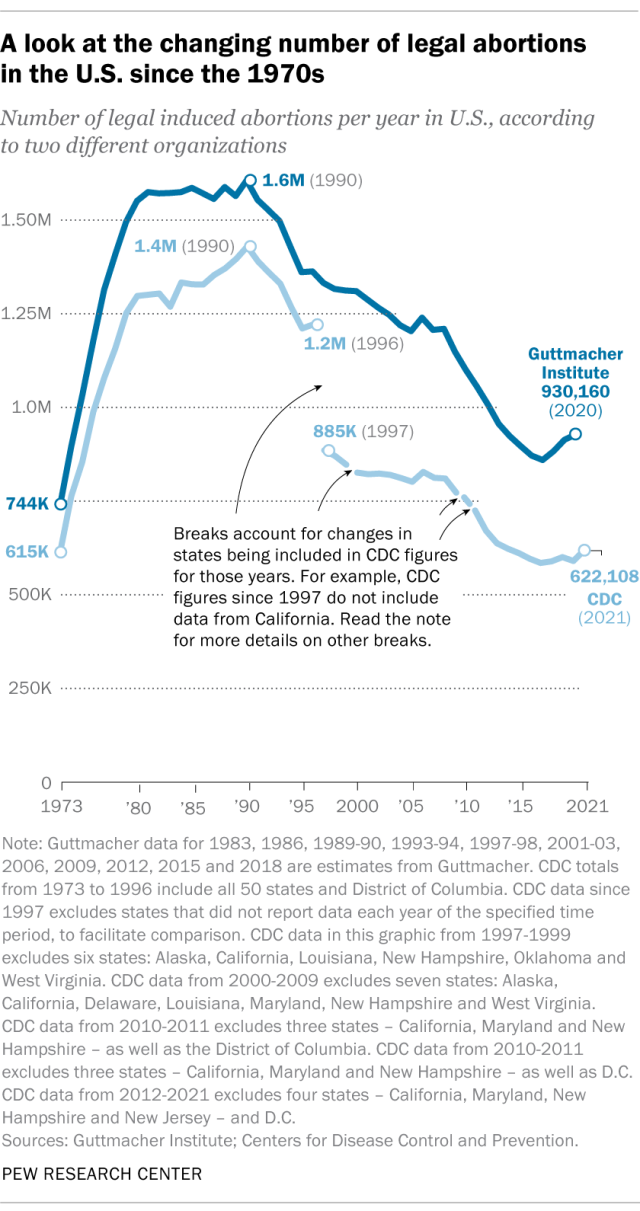

The annual number of U.S. abortions rose for years after Roe v. Wade legalized the procedure in 1973, reaching its highest levels around the late 1980s and early 1990s, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. Since then, abortions have generally decreased at what a CDC analysis called “a slow yet steady pace.”

Guttmacher says the number of abortions occurring in the U.S. in 2020 was 40% lower than it was in 1991. According to the CDC, the number was 36% lower in 2021 than in 1991, looking just at the District of Columbia and the 46 states that reported both of those years.

(The corresponding line graph shows the long-term trend in the number of legal abortions reported by both organizations. To allow for consistent comparisons over time, the CDC figures in the chart have been adjusted to ensure that the same states are counted from one year to the next. Using that approach, the CDC figure for 2021 is 622,108 legal abortions.)

There have been occasional breaks in this long-term pattern of decline – during the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, and then again in the late 2010s. The CDC reported modest 1% and 2% increases in abortions in 2018 and 2019, and then, after a 2% decrease in 2020, a 5% increase in 2021. Guttmacher reported an 8% increase over the three-year period from 2017 to 2020.

As noted above, these figures do not include abortions that use pills obtained outside of clinical settings.

Guttmacher says that in 2020 there were 14.4 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. Its data shows that the rate of abortions among women has generally been declining in the U.S. since 1981, when it reported there were 29.3 abortions per 1,000 women in that age range.

The CDC says that in 2021, there were 11.6 abortions in the U.S. per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44. (That figure excludes data from California, the District of Columbia, Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.) Like Guttmacher’s data, the CDC’s figures also suggest a general decline in the abortion rate over time. In 1980, when the CDC reported on all 50 states and D.C., it said there were 25 abortions per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44.

That said, both Guttmacher and the CDC say there were slight increases in the rate of abortions during the late 2010s and early 2020s. Guttmacher says the abortion rate per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44 rose from 13.5 in 2017 to 14.4 in 2020. The CDC says it rose from 11.2 per 1,000 in 2017 to 11.4 in 2019, before falling back to 11.1 in 2020 and then rising again to 11.6 in 2021. (The CDC’s figures for those years exclude data from California, D.C., Maryland, New Hampshire and New Jersey.)

The CDC broadly divides abortions into two categories: surgical abortions and medication abortions, which involve pills. Since the Food and Drug Administration first approved abortion pills in 2000, their use has increased over time as a share of abortions nationally, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher.

The majority of abortions in the U.S. now involve pills, according to both the CDC and Guttmacher. The CDC says 56% of U.S. abortions in 2021 involved pills, up from 53% in 2020 and 44% in 2019. Its figures for 2021 include the District of Columbia and 44 states that provided this data; its figures for 2020 include D.C. and 44 states (though not all of the same states as in 2021), and its figures for 2019 include D.C. and 45 states.

Guttmacher, which measures this every three years, says 53% of U.S. abortions involved pills in 2020, up from 39% in 2017.

Two pills commonly used together for medication abortions are mifepristone, which, taken first, blocks hormones that support a pregnancy, and misoprostol, which then causes the uterus to empty. According to the FDA, medication abortions are safe until 10 weeks into pregnancy.

Surgical abortions conducted during the first trimester of pregnancy typically use a suction process, while the relatively few surgical abortions that occur during the second trimester of a pregnancy typically use a process called dilation and evacuation, according to the UCLA School of Medicine.

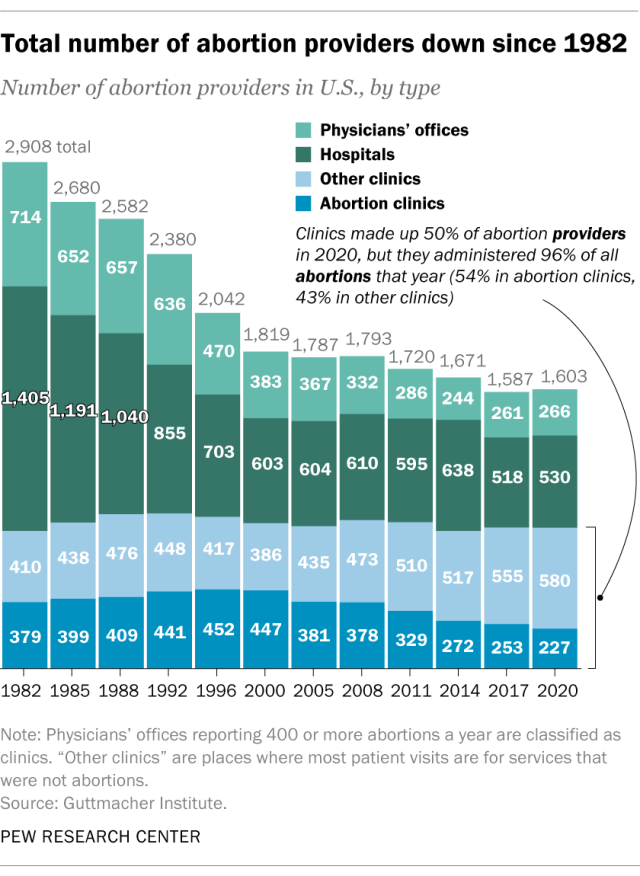

In 2020, there were 1,603 facilities in the U.S. that provided abortions, according to Guttmacher . This included 807 clinics, 530 hospitals and 266 physicians’ offices.

While clinics make up half of the facilities that provide abortions, they are the sites where the vast majority (96%) of abortions are administered, either through procedures or the distribution of pills, according to Guttmacher’s 2020 data. (This includes 54% of abortions that are administered at specialized abortion clinics and 43% at nonspecialized clinics.) Hospitals made up 33% of the facilities that provided abortions in 2020 but accounted for only 3% of abortions that year, while just 1% of abortions were conducted by physicians’ offices.

Looking just at clinics – that is, the total number of specialized abortion clinics and nonspecialized clinics in the U.S. – Guttmacher found the total virtually unchanged between 2017 (808 clinics) and 2020 (807 clinics). However, there were regional differences. In the Midwest, the number of clinics that provide abortions increased by 11% during those years, and in the West by 6%. The number of clinics decreased during those years by 9% in the Northeast and 3% in the South.

The total number of abortion providers has declined dramatically since the 1980s. In 1982, according to Guttmacher, there were 2,908 facilities providing abortions in the U.S., including 789 clinics, 1,405 hospitals and 714 physicians’ offices.

The CDC does not track the number of abortion providers.

In the District of Columbia and the 46 states that provided abortion and residency information to the CDC in 2021, 10.9% of all abortions were performed on women known to live outside the state where the abortion occurred – slightly higher than the percentage in 2020 (9.7%). That year, D.C. and 46 states (though not the same ones as in 2021) reported abortion and residency data. (The total number of abortions used in these calculations included figures for women with both known and unknown residential status.)

The share of reported abortions performed on women outside their state of residence was much higher before the 1973 Roe decision that stopped states from banning abortion. In 1972, 41% of all abortions in D.C. and the 20 states that provided this information to the CDC that year were performed on women outside their state of residence. In 1973, the corresponding figure was 21% in the District of Columbia and the 41 states that provided this information, and in 1974 it was 11% in D.C. and the 43 states that provided data.

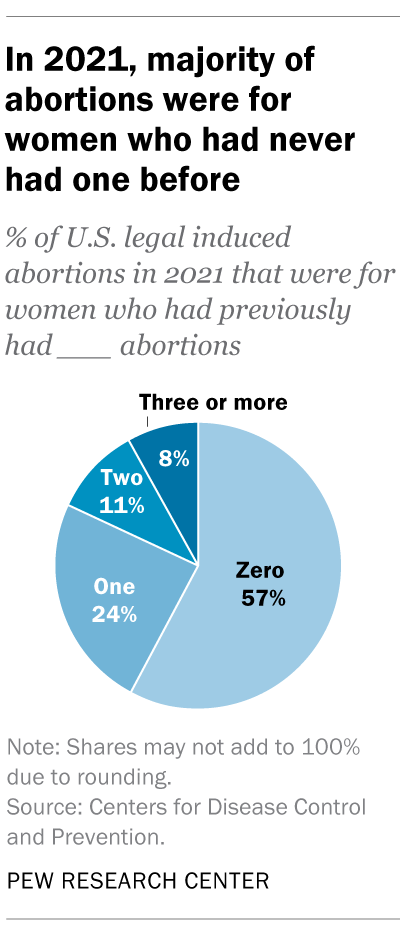

In the District of Columbia and the 46 states that reported age data to the CDC in 2021, the majority of women who had abortions (57%) were in their 20s, while about three-in-ten (31%) were in their 30s. Teens ages 13 to 19 accounted for 8% of those who had abortions, while women ages 40 to 44 accounted for about 4%.

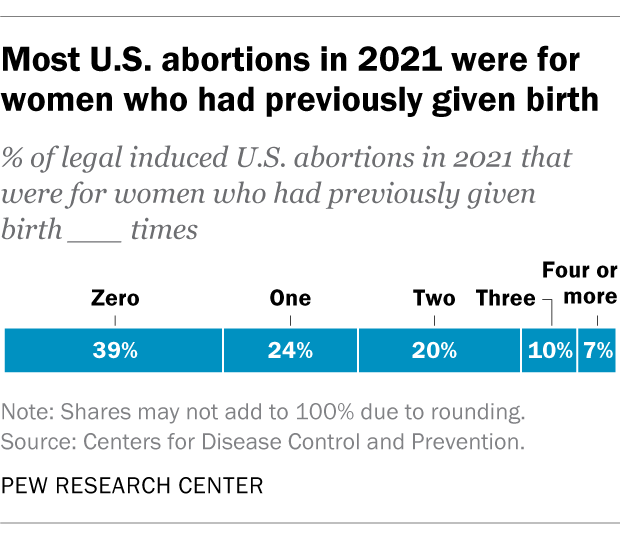

The vast majority of women who had abortions in 2021 were unmarried (87%), while married women accounted for 13%, according to the CDC , which had data on this from 37 states.