More From Forbes

U.s. navy funds new submarine-launched nuclear cruise missile biden called ‘a bad idea’ (updated - acting navy secretary wants to defund).

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Budget documents reveal the U.S. Navy is developing a new nuclear-armed Sea-Launched Cruise Missile, known as SLCM-N. President Biden described the missile as “ a bad idea ” when campaigning in 2019. Though an obvious candidate for cancelation, the SLCM-N program is going ahead.

The need for a new sea-launched cruise missile has been under consideration for some time, with the possibility mentioned in the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review . An un-named Navy functionary told Defense News in February 2020 that it was on their wish list, but the publication of the new R&D budget makes it official: “Project 3467: This project will design, develop, produce and deploy a Nuclear-Armed Sea-Launched Cruise Missile.”

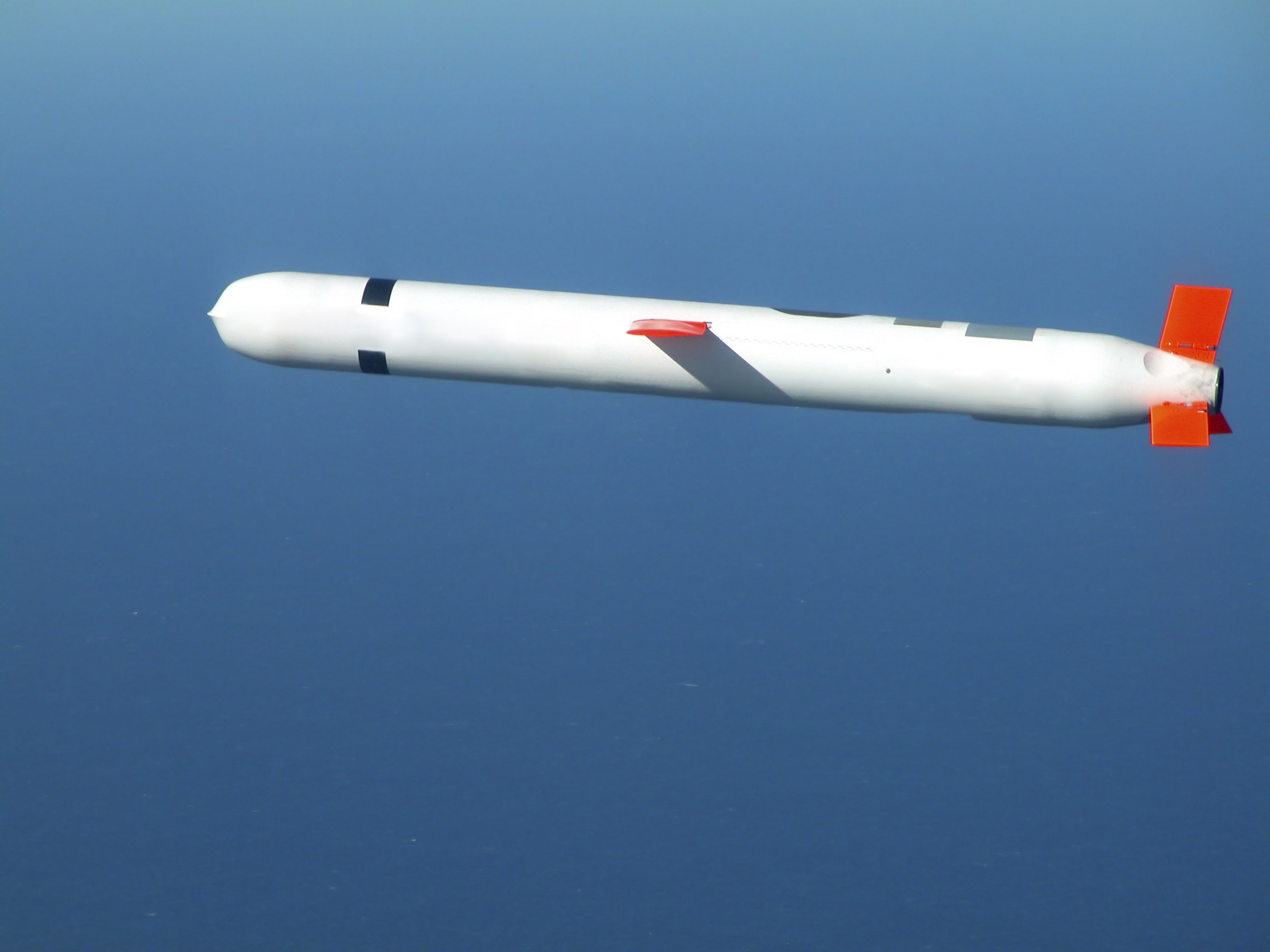

A submarine-launched Tomahawk cruise missile with a conventional warhead. Carrying the nuclear ... [+] version would reduce the number of missiles available for conventional strikes

Conventionally armed BGM-109 Tomahawk cruise missiles are the mainstay of the Navy’s arsenal for attacking land targets. With their long range and high precision, they are useful for taking on highly defended targets, and a salvo of cruise missiles will typically be fired to suppress defenses ahead of a strike by manned aircraft. On occasion, as in the 2018 strikes on Syria , they are used as a low-cost, low-risk alternative to airstrikes.

While not specified, the nuclear cruise missile would be a relatively low-yield weapon compared to the submarine-launched Trident ballistic missiles.

Both surface ships and submarines carry cruise missiles, and previous statements have been carefully ambiguous about which vessels would carry the nuclear version. However, one line in the new R&D budget submission mentions a requirement to “Assess the Virginia Class launch and control facilities to determine the extent of and evaluate for future upgrades.” This indicates that the nineteen nuclear-powered Virginia-class submarines will be launch platforms, in addition to any others selected.

The latest version of the submarine has the new Virginia Payload Module ; in addition to the basic 12 cruise missile launch tubes, the VPM caries and launches up to 28 additional cruise missiles.

Wells Fargo Championship 2024 Golf Betting Preview Odds And PGA Picks

The minnesota timberwolves are suffocating everyone defensively, new fbi warning as hackers strike email senders must do this 1 thing.

Existing conventional cruise missiles have a range of 800-1500 miles depending on the size of the warhead. The nuclear warhead – details yet to be determined – may be somewhat lighter than the conventional payloads, giving longer range. The navy did previously have a nuclear version, the original TLAM-N (“Tomahawk Land Attack Missile-Nuclear) which was quietly retired some years ago . The SLCM-N is in a sense reinventing the wheel.

The 12 vertical-launch Tomahawk missile tubes of the USS Oklahoma City (SSN-723).

Putting nuclear cruise missile on Virginia-class would be a quick and easy way of ramping up strategic capability. Currently, the only nuclear-armed subs are the fourteen Ohio-class ballistic missile subs , so SLCM-N on Virginia-class would more than double that at a stroke.

But there are downsides.

“Putting nuclear-armed missiles back on the conventional surface or attack submarine fleets of the Navy is a real cause for concern,” says Monica Montgomery, a research analyst at the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. “Doing so would erode the higher-priority conventional missions of the Navy by reducing the number of conventional missiles each boat could carry and increase the possibility of conflict escalation through miscalculation by blurring the line between conventional and nuclear cruise missiles on these vessels.”

Montgomery calls the message sent by the SLCM-N develpment “both surprising and troubling,” seeing it as potentially destabilizing, and says the Trump-era proposal should not have gone ahead under the new administration.

“The SLCM-N was truly low-hanging fruit ripe for cancellation in this year’s budget,” says Montgomery.

There is still time for the administration to change its mind in the next Nuclear Posture Review later this year, according to Kingston Reif , Director for Disarmament and Threat Reduction Policy at the Arms Control Association

“Reversing the Trump administration's plan to pursue a nuclear SLCM should be an easy choice,” Reif says.

Reif describes the SLCM-N as “a costly hedge on a hedge” – an extra backup for an already extensive and growing nuclear arsenal – making it a pointless extravagance.

Reif also notes that the nuclear capability will come at the expense of urgently needed conventional weapons.

“Arming such vessels with nuclear cruise missiles would also reduce the number of conventional missiles each boat could carry, at a time when Pentagon leaders argue that strengthening conventional deterrence is their top priority in the Asia-Pacific,” says Reif.

Biden himself noted that fielding low-yield weapons as alternatives to more powerful ballistic missiles would make the U.S. “more inclined to use them” and increase the risk of a nuclear war.

The SLCM-N project is starting small, just $15.2 million in this year’s budget compared to the billions for other nuclear programs. But if the analysts are right, the U.S. Navy is buying trouble rather than new capability.

UPDATE : On June 8th, USNI News reported that acting U.S. Navy Secretary Thomas Harker directed the service to defund nuclear the SLCM-N in fiscal 2023, citing a leaked memo. It seems that there are people inside the Navy who question the value of a nuclear cruise missile too.

A memo of revised guidance indicated the SLCM-N will be cut

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

- Arab-Israeli Relations

- Proliferation

- Palestinians

- Gulf States

Regions & Countries

- Middle East

- North Africa

- Arab & Islamic Politics

- Democracy & Reform

- Energy & Economics

- Great Power Competition

- Gulf & Energy Policy

- Military & Security

- Peace Process

- U.S. Policy

- Policy Analysis

- PolicyWatch 3732

U.S. Deploys Cruise Missile Submarine to Strengthen Deterrence Against Iran

Farzin Nadimi, a Senior Fellow with The Washington Institute, is a Washington-based analyst specializing in the security and defense affairs of Iran and the Persian Gulf region.

Amid rising tensions with Tehran and its proxies, the United States is sending a message by openly deploying one of its few guided missile submarines to the region.

Typically, U.S. submarine deployments are not announced in advance, especially when the vessels are entering a potentially hot zone of operation that may require them to rely on stealth, their main operational advantage. Yet conventionally armed guided missile submarines are an exception—their presence is occasionally made known as a show of deterrence. This seemed to be the main purpose when U.S. Naval Forces Central Command announced on April 8 that the USS Florida (SSGN-728) had been deployed to the Middle East “to help ensure regional maritime security and stability.” The Florida is one of only four guided missile/special forces submarines in U.S. Navy service—vessels that are usually tasked with top-priority clandestine missions.

Increased U.S.-Iran-Israel Clashes

On March 23, a U.S.-manned forward base near Hasaka, Syria, was attacked by an explosive drone launched by Iraqi Shia militias affiliated with Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Among other casualties, an American contractor was killed in the attack—an outcome that crossed Washington’s red lines and triggered multiple U.S. airstrikes inside Syria. Yet those strikes were only partially successful in deterring Iran and its proxies—a salvo of rockets was soon fired at another U.S. compound in Syria, raising concerns about further escalation.

These clashes coincided with a series of Israeli standoff precision airstrikes against IRGC and Hezbollah targets in Syria beginning on March 30. The resultant deaths of two IRGC officers and other operatives prompted Tehran to issue promises of revenge. On April 2, a drone of reportedly Iranian origin tried to penetrate northern Israel from Syria but was shot down. The next day, Israel downed a Hamas Shahab drone as it tried to enter from the Gaza Strip.

Meanwhile, rising tensions in the West Bank led to multiple rocket strikes against Israel, some launched by Palestinian factions in south Lebanon and others from Gaza and Syria. In response, Israel conducted bombing raids targeting the launch sites. The risk of escalation is significant given ongoing tensions at the Temple Mount/al-Haram al-Sharif and Iran’s declared “Qods (Jerusalem) Day,” which falls today, the last Friday of Ramadan. In this environment, the United States and its partners can benefit from the USS Florida’s deterrent effect and robust intelligence collection capabilities—and, if necessary, from its additional firepower.

Signaling with Submarines

According to media reports quoting U.S. defense officials, suspicious Iranian drone activities in the Gulf of Aden, Arabian Sea, and Red Sea spurred the U.S. Navy and United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO) to issue warnings of potential shipping attacks on April 5-6. The warnings were especially geared toward Israeli cargo ships and tankers, which were reportedly asked to navigate away from Iranian waters with their transponders turned off. Since February 2021, the IRGC has attacked Israeli-linked commercial vessels in the Gulf of Oman or Arabian Sea at least seven times, using suicide drones and/or limpet mines to damage the ships and, in one case, kill crewmembers.

It has been a while since the U.S. Navy acknowledged the deployment of a submarine to the region. On December 21, 2020, the USS Georgia —another SSGN, the designation used for nuclear-powered guided missile submarines— transited the Strait of Hormuz while surfacing alongside two U.S. missile cruisers. That deployment came during another period of high tensions marked by two developments: the imminent first anniversary of the U.S. strike that killed IRGC Qods Force commander Qasem Soleimani, and the November assassination of top Iranian nuclear official Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, allegedly by Israel. At the time, the Nimitz Carrier Strike Group was also deployed to the northern Arabian Sea to support troop withdrawals from Iraq and Afghanistan.

Another high-profile deployment came on October 19, 2022, when U.S. Central Command chief Gen. Michael Kurilla was given a tour of the ballistic missile submarine USS West Virginia in the Arabian Sea. These vessels are considered key tools of strategic deterrence and part of the U.S. nuclear triad, and they do not often patrol in the Middle East. The move was interpreted as a message to Russian president Vladimir Putin (who had recently threatened to use nuclear weapons in Ukraine) and Iran (which had been supplying Moscow with suicide drones for use in Ukraine, and possibly short-range ballistic missiles as well).

How Could an SSGN Be Used Against Iran?

The Navy’s four converted Ohio -class SSGNs are usually tasked with highly secretive intelligence gathering and conventional strike missions. They are armed with up to 154 vertically launched precision-guided TLAM-E Tomahawk cruise missiles (UGM-109E Block IV) with a range of up to 1,600 km and a 454 kg warhead. This version of the Tomahawk is capable of loitering in flight and has a two-way satellite datalink that can receive updated mission data for retargeting, course corrections, and damage assessment. This ability is especially useful for targeting air defense systems and mobile ballistic missile launchers.

The 1,600 km range could enable an SSGN submerged at a safe distance in the Arabian Sea to clandestinely launch cruise missiles at targets deep inside Iran, using any ingress point along its 784 km coastline with the Gulf of Oman and most of its 1,600 km land borders with Pakistan and Afghanistan. This puts all of the regime’s military sites, military industrial facilities, and other targets in the south and east within striking range, as well as some of its main nuclear sites. Although the TLAM-E does not have significant hard-target penetration capabilities, its multi-effect programmable warhead still allows for some degree of “bunker busting,” especially when several missiles hit a single point sequentially.

With a vessel like the USS Florida in theater, Iran’s monitoring capabilities and cruise missile defenses along these vast and remote borders could be stretched quite thin (for a more detailed discussion of the regime’s air defense, including graphics, see PolicyWatch 3626 ). In January 2021, false reports of penetration by American cruise missiles from several directions reportedly caused confusion within Iran’s military command following its strike against al-Asad Air Base in Iraq—so much so that an IRGC TOR-M1 short-range air defense system shot down a Ukrainian civilian airliner near Tehran.

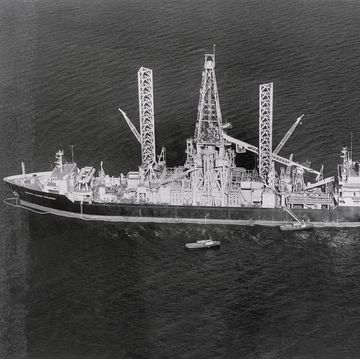

Converted Ohio -class submarines are also equipped with a thirty-ton dry deck shelter. This gives them the ability to deliver and recover SEAL commando teams on clandestine missions using submersibles or small boats.

These capabilities, coupled with robust intelligence gathering and task force command-level secure communications, give SSGNs carrier-like abilities when a carrier is not available. SSGNs also offer logistical advantages compared to a carrier strike group, such as quicker deployment and concealment of their whereabouts—though as noted above, the Pentagon will sometimes publicize a submarine deployment to achieve the same deterrent effects as a carrier presence.

In the current case, the Florida was apparently forward-deployed to the Middle East because the Russia-focused mission of the George H. W. Bush Carrier Strike Group in the East Mediterranean has been extended. Although the carrier group can still project airpower into Syria from the Mediterranean, cruise missiles launched by the Florida would offer a much better alternative against potential targets in both Iran and eastern/southern Syria, which could be struck from standoff range in the Arabian Sea or Gulf of Oman. Low-flying Tomahawks are difficult to detect and counter, especially if launched from submerged SSGNs.

Interestingly, Tehran is eyeing a stealthy submarine launch capability of its own. Since at least 2019, the Iranian national navy has been developing and testing a canister-based system for launching Nasr antiship missiles from submarine torpedo tubes; these missiles now have a reported range of around 100 km. Iranian submarines still lack slant or vertical launch systems for long-range cruise missiles, but the regime is likely working on this capability.

Despite making overtures to American partners in the Gulf, Iran is still committed to pushing the United States out of the region and posing a clear and present danger to its forces in Syria and elsewhere. It has also been developing “anti-carrier” capabilities in the form of antiship homing ballistic missiles with a claimed range of up to 2,000 km.

In this environment, the U.S. Navy’s flexible and stealthy guided missile submarines are an excellent alternative to carrier deployments when needed, providing a way to enhance deterrence against Tehran and its proxies by maintaining a persistent clandestine presence—and delivering occasional public reminders of U.S. firepower. Notably, all four SSGNs are slated for retirement between 2026 and 2028, with no replacement in sight. Until then, however, the prospect of 154 Tomahawks causing massive damage inside Iran could send a powerful message, since the regime is obviously much more sensitive to potential strikes on its home territory versus far away in Syria.

Farzin Nadimi is an associate fellow with The Washington Institute, specializing in security and defense in Iran and the Gulf region.

Recommended

- Michael Knights

- Amir al-Kaabi

- Hamdi Malik

- Mohammed Hussein

- Soner Cagaptay

Regions & Countries

Stay up to date.

North Korea tests submarine-launched cruise missiles, KCNA says

- Medium Text

Sign up here.

Reporting by Jack Kim; Editing by Andrew Cawthorne, Lisa Shumaker, Leslie Adler and Diane Craft

Our Standards: The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles. New Tab , opens new tab

World Chevron

US warns Israel that Rafah invasion will jeopardise weapons supply as assault continues

U.S. President Joe Biden vowed publicly for the first time to withhold weapons from Israel if its forces make a major invasion of Rafah in southern Gaza while negotiations in Cairo on a ceasefire plan for the enclave were set to continue on Thursday.

Air Vanuatu said on Thursday it had cancelled international flights for the rest of the week, as the Pacific Island nation's government considered placing its national carrier into voluntary administration.

- Books & Press

- Proceedings

- Naval History

Suggestions

Trending topics, nuclear sea-launched cruise missile has ‘zero value,’ latest nuclear posture review finds.

THE PENTAGON — The Defense Department officially abandoned the effort to pursue a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile, according to the Nuclear Posture Review unveiled today.

The SLCM-N initiative, which received support from the Joint Chiefs and U.S. Strategic Command, was found to be of “zero value” in the most recent U.S. nuclear weapons review, a senior defense official told reporters in a Thursday briefing.

“Everyone’s voice has been heard. As it applies to the current situation – Russia [and] Ukraine – [it] has zero value because even at the full funding value it would not arrive until 2035,” the senior defense official said. “Our deterrence posture is firm. Russia’s been deterred from attacking NATO. We continue to focus on Russia and China. I think as it stands right now, there is no need to develop SLCM.”

While the Fiscal Year 2023 budget proposal canceled the SLCM(N) program, the unclassified version of the Nuclear Posture Review released Thursday explained detailed the Biden administration’s rationale for abandoning the program. The idea of a sea-launched nuclear cruise missile was introduced in the 2018 NPR to provide a low-yield warhead option as a response to the use of an adversary’s tactical nuclear weapon. In addition, the U.S. developed the low-yield W76-2 warhead for its ballistic nuclear missile submarine fleet.

“The 2018 NPR introduced SLCM-N and the W76-2 to supplement the existing nuclear program of record in order to strengthen deterrence of limited nuclear use in a regional conflict,” reads the report. “We reassessed the rationale for these capabilities and concluded that the W76-2 currently provides an important means to deter limited nuclear use.”

The first reported use of the W76-2 was aboard USS Tennessee (SSBN-734) on a deterrent patrol beginning in 2019.

Republican lawmakers questioned the Pentagon’s plans to cancel the SLCM-N program following a USNI News report last year on a Navy budget document that called for eliminating the program.

“Our inventory of nuclear weapons is significant. We determined as we looked at our inventory that we don’t need that capability,” Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin told reporters on Thursday.

The Defense Department released the NPR on Thursday along with the 2022 National Defense Strategy that is the Pentagon’s contribution to the National Security Strategy and an update to the 2018 NDS .

In the series of strategy documents released Thursday, the Pentagon emphasized its focus on the People’s Republic of China as the so-called “pacing threat.”

The 2022 NDS, which builds upon the 2018 NDS released under the Trump administration, cites China’s increased aggression in the Indo-Pacific region and its military modernization efforts.

“The PRC’s increasingly provocative rhetoric and coercive activity towards Taiwan are destabilizing, risk miscalculation, and threaten the peace and stability of the Taiwan Strait. This is part of a broader pattern of destabilizing and coercive PRC behavior that stretches across the East China Sea, the South China Sea, and along the Line of Actual Control,” reads the NDS. “The PRC has expanded and modernized nearly every aspect of the PLA, with a focus on offsetting U.S. military advantages.”

In addition to the NDS and the Nuclear Posture Review, the Defense Department also released a Missile Defense Review that identifies both China’s and Russia’s missile modernization, including hypersonic weapons, as a persistent challenge to U.S. forces.

The report specifically cited the defense of Guam as a concern.

“The architecture for defense of the territory against missile attacks will therefore be commensurate with its unique status as both an unequivocal part of the United States as well as a vital regional location. Guam’s defense, which will include various active and passive missile defense capabilities, will contribute to the overall integrity of integrated deterrence and bolster U.S. operational strategy in the Indo-Pacific region,” reads the report.

In addition to precision-guided weapons, the Russian use of unguided weapons in Ukraine added concern to missile defense beyond Europe.

“Russia has been indiscriminately using thousands of offensive missiles in Ukraine, and mainly not for precision military effects but instead as broad area terror weapons to inflict terrible hardships on innocent civilians. Their use of missiles in Ukraine shows we should expect these weapons to become a common feature of 21st-century conflict,” the defense official said.

Mallory Shelbourne

Mallory Shelbourne is a reporter for USNI News. She previously covered the Navy for Inside Defense and reported on politics for The Hill . Follow @MalShelbourne

Get USNI News updates delivered to your inbox

Email address:

Frequency Daily Weekly All

Related Topics

- News & Analysis

- Submarine Forces

- Surface Forces

Related Posts

Carrier USS Dwight D. Eisenhower Back in Red Sea, Passes 200-Day Deployment Mark

Chinese Fighter Drops Flares in Front of Aussie Helo in ‘Unprofessional’ Action, Say Officials

USNI News Fleet and Marine Tracker: May 6, 2024

Chinese Aircraft Carrier Fujian Leaves for First Set of Sea Trials

North Korea says it has tested submarine-launched cruise missiles

SEOUL, South Korea — North Korean leader Kim Jong Un supervised test firings of new cruise missiles designed to be launched from submarines and also reviewed efforts to build a nuclear-powered submarine while reiterating his goal of building a nuclear-armed navy to counter what he portrays as growing external threats, state media said Monday.

The report came a day after South Korea’s military said it detected North Korea firing multiple cruise missiles over waters near the eastern port of Sinpo, where the North has a major shipyard developing submarines. It was the latest in a streak of weapons demonstrations by North Korea amid increasing tensions with the United States, South Korea and Japan.

North Korea’s official newspaper Rodong Sinmun published photos of what appeared to be at least two missiles fired separately. Both created grayish-white clouds as they broke the water surface and soared into the air at an angle of around 45 degrees, which possibly suggests they were fired from torpedo launch tubes.

State media said the missiles were Pulhwasal-3-31, a new type of weapon first tested last week in land-based launches from North Korea’s western coast.

The reports implied that two missiles were fired during the test. KCNA said the missiles flew more than two hours before accurately striking an island target, but it did not specify the vessel used for the launches. North Korea in past years has fired missiles both from developmental, missile-firing submarines and underwater test platforms built on barges.

Lee Sung Joon, spokesperson for South Korea’s Joint Chiefs of Staff, said the South Korean and U.S. militaries were analyzing the launches, including the possibility that the North exaggerated the flight times.

In recent years, North Korea has tested a variety of missiles designed to be fired from submarines as it pursues the ability to conduct nuclear strikes from underwater. In theory, such capacity would bolster its deterrent by ensuring a survivable capability to retaliate after absorbing a nuclear attack on land.

Missile-firing submarines would also add a maritime threat to the North’s growing collection of solid-fuel weapons fired from land vehicles that are designed to overwhelm the missile defenses of South Korea, Japan and the United States.

Still, it would take considerable time, resources and technological improvements for the heavily sanctioned nation to build a fleet of at least several submarines that could travel quietly and execute attacks reliably, analysts say.

The North’s official Korean Central News Agency said Kim expressed satisfaction after the missiles accurately hit their sea targets during Sunday’s test.

He then issued unspecified important tasks for “realizing the nuclear weaponization of the navy and expanding the sphere of operation,” which he described as crucial goals considering the “prevailing situation and future threats,” the report said. KCNA said Kim was also briefed on efforts to develop a nuclear-propelled submarine and other advanced naval vessels.

Kim issued similar comments about a nuclear-armed navy in September while attending the launching ceremony of what the North described as a new submarine capable of firing tactical nuclear weapons from underwater . He said then that the country was pursuing a nuclear-propelled submarine and that it plans to remodel existing submarines and surface vessels so they can handle nuclear weapons.

Nuclear-propelled submarines can quietly travel long distances and approach enemy shores to deliver strikes, which would bolster Kim’s declared aim of building a nuclear arsenal that could viably threaten the U.S. mainland. But experts say such vessels are most likely unfeasible for the North without external assistance in the near term.

North Korea has an estimated 70 to 90 diesel-powered submarines in one of the world’s largest submarine fleets. But they are mostly aging vessels capable of launching only torpedoes and mines.

South Korea’s military said the submarine unveiled by North Korea in September, the “Hero Kim Kun Ok,” did not look ready for operational duty and suggested the North was exaggerating its capabilities.

Tensions on the Korean Peninsula have increased in recent months as Kim accelerates his weapons development and issues provocative threats of nuclear conflict with the U.S. and its Asian allies.

The U.S., South Korea and Japan in response have been expanding their combined military exercises, which Kim condemns as invasion rehearsals, and sharpening their deterrence strategies built around nuclear-capable U.S. assets.

The Associated Press

- Air Warfare

- Cyber (Opens in new window)

- C4ISR (Opens in new window)

- Training & Sim

- Asia Pacific

- Mideast Africa

- The Americas

- Top 100 Companies

- Defense News Weekly

- Money Minute

- Whitepapers & eBooks (Opens in new window)

- DSDs & SMRs (Opens in new window)

- Webcasts (Opens in new window)

- Events (Opens in new window)

- Newsletters (Opens in new window)

- Events Calendar

- Early Bird Brief

- Digital Edition (Opens in new window)

Satellite photo shows possible new Chinese nuclear submarine able to launch cruise missiles

MELBOURNE, Australia — A submarine seen in a satellite photo of a Chinese shipyard shows what could be a new class or subtype of a nuclear-powered attack sub with a new stealthy propulsion system and launch tubes for cruise missiles.

The satellite photo of the shipyard at Huludao in Liaoning province, northern China, which was provided to Defense News by Planet Labs, was taken May 3 and shows a submarine on a drydock.

The unidentified boat’s presence at the yard was first noted in an April 29 satellite image by geospatial intelligence outfit AllSource Analysis. The organization said the submarine is possibly a new class undergoing construction by China.

The submarine has two distinct patches of green coloring on its hull immediately behind its conning tower, while a cruciform rudder arrangement and a possible shrouded propulsion system are seen.

A naval expert told Defense News he has “moderately high confidence” the submarine includes a row of vertical launch system cells for submarine-launched missiles and a shroud for pump-jet propulsion.

Collin Koh at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies told Defense News that China has conducted research into submarine pump-jet propulsion, citing previously published scientific literature.

Having submarines capable of launching cruise missiles for land-attack and anti-ship missions fits into China’s pursuit of long-range offensive strike capabilities, he said, adding that these include the capability to target U.S. Navy assets and distant land targets, such as those in Guam, where American forces are based.

If the rectangular section on the submarine, as seen in the satellite photo, is indeed a set of VLS cells, it would be in line with a 2021 Pentagon report on China’s military power that the country was likely building “the Type 093B guided-missile nuclear attack submarine.”

The sighting of the new submarine comes after a model of a nuclear-powered attack submarine bearing the nameplate of China State Shipbuilding Corporation Limited and fitted with VLS technology as well as pump-jet propulsion appeared online. (China’s two largest shipbuilding conglomerates, China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation and China State Shipbuilding Corporation, merged in November 2019 to create the business .)

The model, which features 18 VLS cells in three rows of six missile tubes behind the boat’s conning tower, was posted on Chinese social media without the shipyard’s plaque in early May. Some speculated this was a development of the Type 093 class tentatively named Type 093B.

The submarine seen in the latest satellite image of Huludao appears to measure up closely to the Type 093′s 110-meter length, indicating it is likely a development of the Type 093 rather than an altogether new class.

The Type 093 is also known as the Shang class; the Pentagon’s report noted the “new Shang class variant will enhance the PLAN’s [People’s Liberation Army Navy’s] anti-surface warfare capability and could provide a clandestine land-attack option if equipped with land-attack cruise missiles (LACMs).”

The Type 093 and the follow-on Type 093A Shang-II-class boats displace about 6,100 tons each when submerged. China has six Type 093s, including the “A” variant. Their commissioning began in 2006, with each successive boat featuring slight differences in sail design and a hump behind the conning tower, whose purpose has yet to be disclosed nor been fully understood.

Mike Yeo is the Asia correspondent for Defense News.

More In Naval

Biden says US won’t supply weapons for Israel to attack Rafah

U.s. will still supply iron dome rocket interceptors and other defensive arms..

NATO drone surveillance hours surge amid growing appetite for intel

“the north atlantic security environment is under threat,” said scott bray, the assistant secretary general for intelligence and security..

Pentagon innovation chief calls for bigger, faster Replicator 2.0

Defense innovation unit head doug beck outlined his goals for the next version of the drone program, even while the first is a work in progress..

Stingy intel-sharing a ‘recipe for losing,’ Space Force’s Miller says

"the united states does not go into conflict alone," lt. gen. david miller said at the geoint conference. "check your history. it does not happen.".

Teledyne unveils Rogue 1 exploding drone sought by Marine Corps

Should the rogue 1 drone not explode or be recalled, it can be disarmed and reused thanks to a mechanical disconnect., featured video, with insurgents pouring over a wall in afghanistan, this sgt. took them on with only his pistol.

New thermal optics and more at Modern Day Marine 2024 | Defense News Weekly Full Episode 5.4.24

How can I start prepping for upcoming school year expenses? — Money Minute

Thermal / red dot combo on display at Modern Day Marine

Trending now, special operators set to pick light machine gun in new caliber, sweden goes back to the drawing board for a next-gen warplane, how dc became obsessed with a potential 2027 chinese invasion of taiwan, missile mishaps, ammo snags – report details danish frigate deployment, one defense strategy, two drastically different budgets.

A Short History of Cruise Missiles: The Go-To Weapons for Conventional Precision Strikes

The slow, stubby-winged cruise missile has become a major part of modern warfare. This is its story.

- They’re not like other missiles; instead, cruise missiles work more like drones.

- Ironically, the inspiration for the first cruise missiles involved pilots—the infamous kamikazes of World War II .

One weapon that establishes a military power in a completely different category from the rest is the cruise missile. Originally designed to deliver nuclear weapons at long distances, it’s become the go-to weapon for conventional precision strikes, and is currently front and center in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But as the cruise missile is now in its fifth decade of use, there are signs it’ll need some adjustments to stay relevant on the modern battlefield .

Divine Wind

A cruise missile is a subsonic guided missile that uses a turbojet, a smaller version of the jet engines that power today’s airplanes , to reach its targets. Cruise missiles often have small, stubby wings to allow them to bank and turn, following an invisible flight path in the sky. Modern cruise missiles use satellite navigation to guide themselves to target, and some can even take pictures of the target area, allowing operators to retarget them in midair. The missile’s payload is typically a warhead in the 1,000-pound weight class, often with the ability to penetrate earth and concrete to target underground shelters.

The first cruise missiles were Japan’s kamikaze planes of World War II. The kamikaze, or “divine wind,” was part of the Japanese Special Attack Units. Created out of desperation and meant to curb the inexorable advance of U.S. forces across the Pacific, kamikaze pilots were sent on one-way missions to target ships of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. The planes were loaded with explosives, and the pilots flew low and fast to avoid detection until the last possible moment.

Kamikaze missions were incredibly successful. In the first four months of their use, an estimated 34 percent of all kamikazes reached their targets. Much of their success is likely attributable to American forces’ disbelief that pilots could commit suicide for their mission. But the low-flying mission profile and the pilot’s ability to recognize threats and avoid them were also undoubtedly factors. In the 1970s, when U.S. military planners originally conceived of the cruise missile, the kamikazes were likely not far from anyone’s mind.

How Cruise Missiles Work

Cruise missiles were originally designed to carry nuclear weapons long distances, allowing bombers to strike their targets without entering the range of an adversary’s air-defense weapons. Conventional rocket-powered missiles didn’t fit the bill: rocket engines are designed to provide speed, and burn up fuel quickly. A cruise missile would need an enormous rocket engine to reach a distant target, with the result being a missile so big only a few would be able to fit inside a bomber.

Instead of rockets, engineers took a different tack: small turbofan engines that burn jet fuel. Turbofan engines are much more efficient, allowing a 21-foot-long missile to carry enough fuel to fly 1,000 miles, plus a 1,000-pound high-explosive warhead (or W-80 thermonuclear warhead ) and a guidance system. The downside was that a turbofan-powered cruise missile could not fly particularly fast, just about 500 miles per hour.

A subsonic cruise missile flying a straight flight path and unable to take evasive action would prove easy meat to any enemy interceptor that happened upon it. The first modern cruise missile, the American-made Tomahawk , was designed to fly low, less than 100 meters above the ground. This limited the range at which ground-based radars could detect a cruise missile, as radar waves conform to the curvature of Earth. This also frustrated enemy fighters, whose nose-mounted radars found it difficult to pick out a cruise missile against the clutter created by the ground below. While cruise missiles were too slow to become first-strike weapons, they were effective for retaliatory strikes against heavily defended airspace.

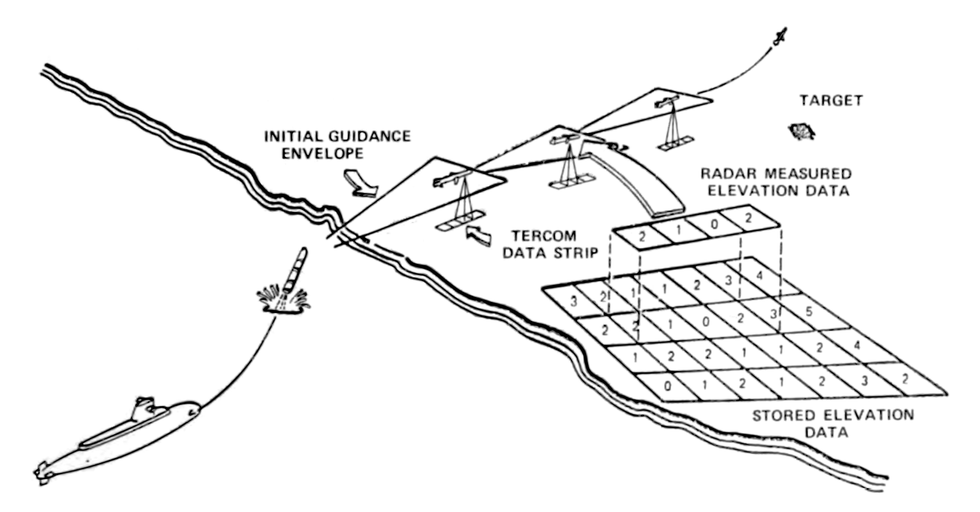

Early Tomahawk cruise missiles followed a pre-programmed flight path to target using a system called terrain contour matching (TERCOM). In TERCOM , a radar altimeter scans the terrain below the missile, then compares it to a terrain elevation map stored in its onboard computer brain. If the two match, the missile is on the right flight path; if they don’t match, the missile adjusts course. Programming TERCOM for a long-range mission was a notoriously time-consuming process, and had to be done at a computer terminal.

As the Tomahawk neared its target, it switched over to a completely different navigation system: digital scene matching and area correlation ( DSMAC ). DSMAC used an optical sensor that took pictures of the ground and compared them to actual sites on the final route to the target. Together, TERCOM and DSMAC delivered unheard of accuracy, allowing Tomahawks to fly hundreds of miles and strike specific parts of land targets, even specific parts of buildings.

More recent cruise missiles, including newer versions of the Tomahawk, have done away with the old navigation systems in favor of using GPS to guide themselves to a fixed target. This has had the effect of making an already accurate missile even more accurate—reportedly to within 32 feet of a target. The Tomahawk Block IV version, introduced in the 2010s, included a camera that could send back imagery to the missile’s controllers, allowing a missile to be re-tasked in midair if its target was already destroyed. Block Va, the latest version, adds the ability to target and attack moving ships at sea.

The Tomahawk missile was the first cruise missile fired in anger. U.S. Navy warships fired a total of 288 Tomahawks during Operation Desert Storm in 1991. Tomahawk missiles have also been fired at Bosnia, Sudan, Syria , Yemen, Libya, Somalia, and Afghanistan. U.S. and U.K. forces have delivered just over 2,000 Tomahawk missiles against operational targets, with more than half against Iraq.

In recent years, other countries have also used cruise missiles in combat. In October 2017, Russia began cruise missile strikes against so-called terrorist targets in Syria. These Novator 3M14 Kalibr cruise missiles are very similar to Tomahawk missiles, but use Russia’s GLONASS satellite navigation system, an alternative to the American GPS. Russia has launched a steady stream of air- and sea-launched cruise missiles against Ukraine since the early hours of the invasion on February 24, 2022 , but a shrinking missile stockpile has led to the attacks becoming less frequent, supplemented by Iranian-made kamikaze drones.

The war in Ukraine has also seen the use of two European cruise missiles, the U.K.’s Storm Shadow and the French SCALP missile . The two are essentially the same, with a 340-mile range and 990-pound warhead. The missiles donated to Ukraine are launched from specially modified Su-24 Soviet-era strike jets . Storm Shadow/SCALP was also used against the Khaddafi regime in Libya in 2011, ISIS in 2015, and by Saudi Arabia against Yemeni rebels in 2016.

The Russo-Ukrainian War has also confirmed an important, long suspected fact: low-flying, subsonic cruise missiles are vulnerable to man-portable surface-to-air missiles. In 2022, a Ukrainian National Guardsman was filmed shooting down a Russian cruise missile with an Igla surface-to-air missile. It was the first known case of a shoulder-fired missile, typically carried by infantry, shooting down a multi-million dollar cruise missile. How this event will affect future cruise missiles remains to be seen.

The Takeaway

Cruise missiles have dramatically changed warfare, as one might expect from a weapon that can fly 1,000 miles and deliver a half-ton high-explosive warhead within 32 feet of a target. The missiles allow countries that can afford them the ability to execute precision strikes on heavily defended targets without endangering pilots or aircraft.

The war in Ukraine will likely impart lessons on the next generation of cruise missiles , but the platform isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Kyle Mizokami is a writer on defense and security issues and has been at Popular Mechanics since 2015. If it involves explosions or projectiles, he's generally in favor of it. Kyle’s articles have appeared at The Daily Beast, U.S. Naval Institute News, The Diplomat, Foreign Policy, Combat Aircraft Monthly, VICE News , and others. He lives in San Francisco.

.css-cuqpxl:before{padding-right:0.3125rem;content:'//';display:inline;} Pop Mech Pro .css-xtujxj:before{padding-left:0.3125rem;content:'//';display:inline;}

Special Ops Gunship Shreds “Fishing Boat”

Russia's Unprecedented Nuclear Drills

Henrietta Lacks Never Asked to Be Immortal

Ukraine Is Using an Ancient Weapon on Russia

Inside the CIA’s Quest to Steal a Soviet Sub

Jumpstart Your Car With a Cordless Tool Battery

Lost Villa of Rome’s Augustus Potentially Found

Could Freezing Your Brain Help You Live Forever?

Air Force’s Combat Drone Saga Has Taken a Turn

China’s Building a Stealth Bomber. U.S. Says ‘Meh’

A Supersonic Bomber's Mission Ended in Flames

Read the May magazine issue on food and climate change

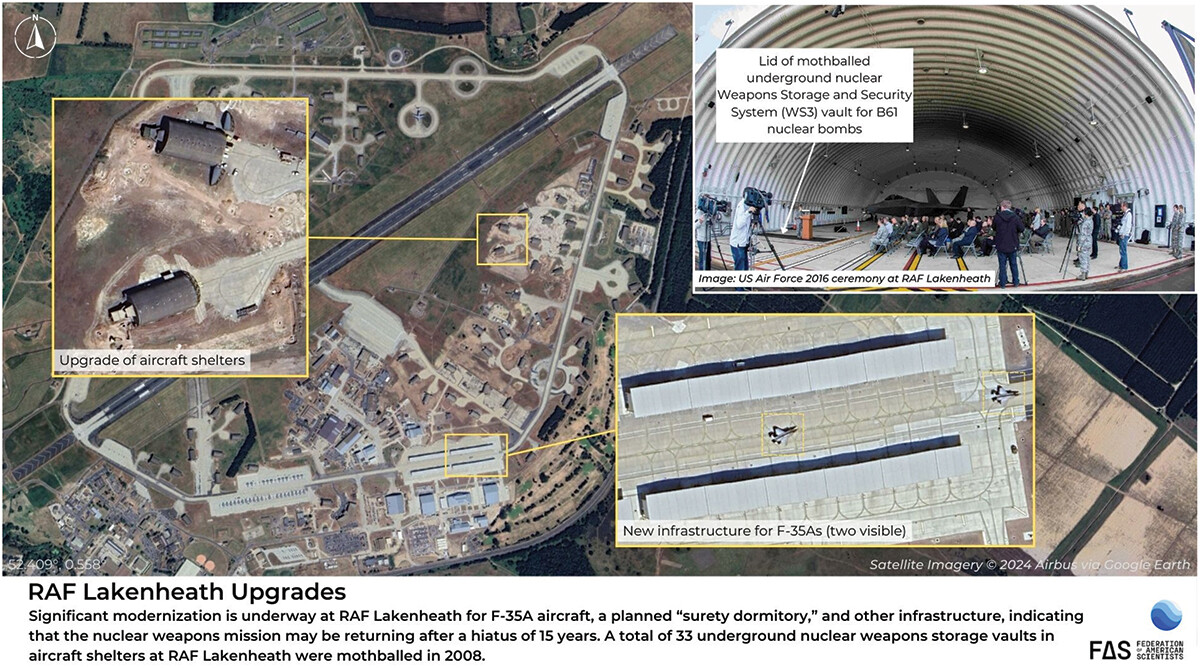

United States nuclear weapons, 2024

By Hans M. Kristensen , Matt Korda , Eliana Johns , Mackenzie Knight | May 7, 2024

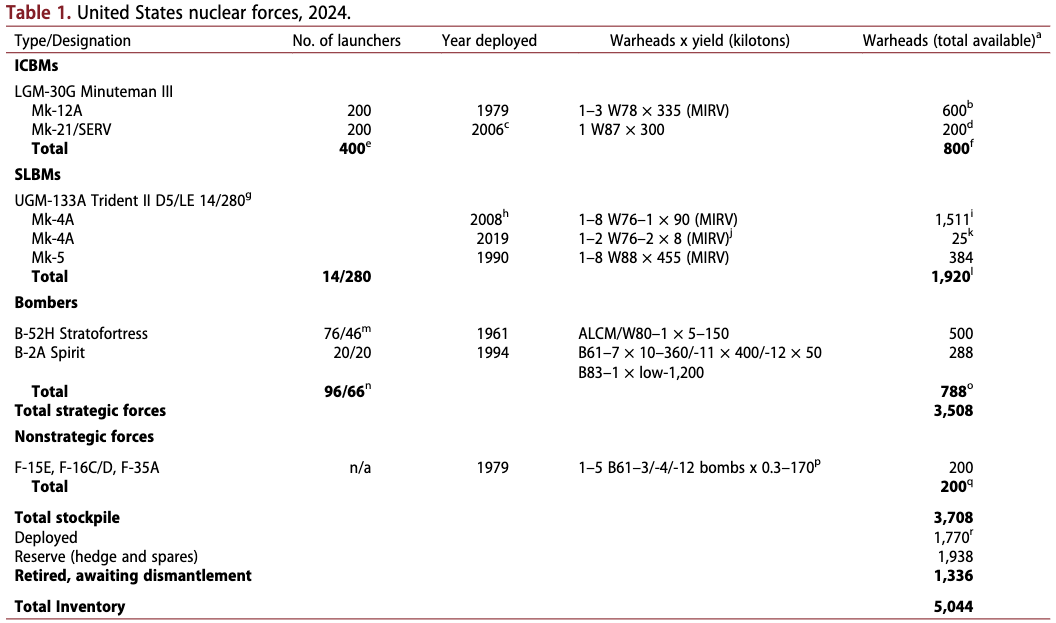

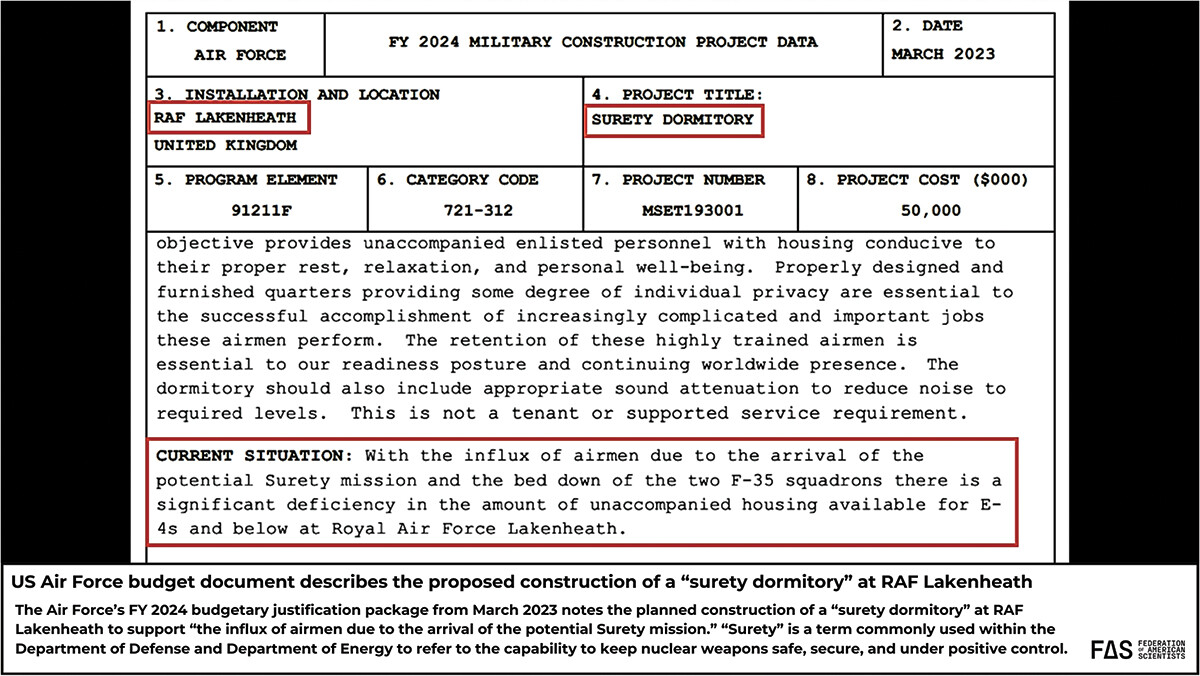

The United States has embarked on a wide-ranging nuclear modernization program that will ultimately see every nuclear delivery system replaced with newer versions over the coming decades. In this issue of the Nuclear Notebook, we estimate that the United States maintains a stockpile of approximately 3,708 warheads—an unchanged estimate from the previous year. Of these, only about 1,770 warheads are deployed, while approximately 1,938 are held in reserve. Additionally, approximately 1,336 retired warheads are awaiting dismantlement, giving a total inventory of approximately 5,044 nuclear warheads. Of the approximately 1,770 warheads that are deployed, 400 are on land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, roughly 970 are on submarine-launched ballistic missiles, 300 are at bomber bases in the United States, and approximately 100 tactical bombs are at European bases. The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by the staff of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project: director Hans M. Kristensen, senior research fellow Matt Korda, research associate Eliana Johns, and program associate Mackenzie Knight.

This article is freely available in PDF format in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ digital magazine (published by Taylor & Francis) at this link . To cite this article, please use the following citation, adapted to the appropriate citation style: Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, United States nuclear weapons, 2024, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists , 80:3, 182-208, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2024.2339170

To see all previous Nuclear Notebook columns in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists dating back to 1987, go to https://thebulletin.org/nuclear-notebook/ .

In May 2024, the US Department of Defense maintained an estimated stockpile of approximately 3,708 nuclear warheads for delivery by ballistic missiles and aircraft. Most of the warheads in the stockpile are not deployed but rather stored for potential upload onto missiles and aircraft as necessary. We estimate that approximately 1,770 warheads are currently deployed, of which roughly 1,370 strategic warheads are deployed on ballistic missiles and another 300 at strategic bomber bases in the United States. An additional 100 tactical bombs are deployed at air bases in Europe. The remaining warheads—approximately 1,938—are in storage as a so-called “hedge” against technical or geopolitical surprises. Several hundred of those warheads are scheduled to be retired before 2030 (see Table 1).

While the majority of the United States’ warheads comprises the Department of Defense’s military stockpile, retired warheads under the custody of the Department of Energy awaiting dismantlement constitute a “significant fraction” of the United States’ total warhead inventory (US Department of Energy 2023b). Dismantlement operations include the disassembly of retired weapons into component parts that are then assigned for reuse, storage, surveillance, or for additional disassembly and subsequent disposition (US Department of Energy 2023b, 2–11). The pace of warhead dismantlement has slowed significantly in recent years: While the United States dismantled on average more than 1,000 warheads per year during the 1990s, in 2020 it dismantled only 184 warheads (US State Department 2021). According to the Department of Energy, “[d]ismantlement rates are affected by many factors, including appropriated program funding, logistics, legislation, policy, directives, weapon system complexity, and the availability of qualified personnel, equipment, and facilities” (US Department of Energy 2022, 2–15). The US Department of Energy stated in April 2023 that it “was on pace to complete the dismantlement of all warheads retired before Fiscal Year (FY) 2009 [Sep. 2008] by the end of FY 2022 [Aug. 2022]” but that the COVID-19 pandemic “delayed the dismantlement of a small number of these retired warheads until after FY 2022 [Aug. 2022]” (US Department of Energy 2023a, 2–12).

Based on these timelines and recent dismantlement rates, we estimate that the United States possesses approximately 1,336 retired—but still intact—warheads awaiting dismantlement, giving a total estimated US inventory of approximately 5,044 warheads.

Between 2010 and 2018, the US government publicly disclosed the size of the nuclear weapons stockpile; however, in 2019 and 2020, the Trump administration rejected requests from the Federation of American Scientists to declassify the latest stockpile numbers (Aftergood 2019; Kristensen 2019a, 2020b). In 2021, the Biden administration restored the United States’ previous transparency levels by declassifying both numbers for the entire history of the US nuclear arsenal until September 2020—including the missing years of the Trump administration. This effort revealed that the United States’ nuclear stockpile consisted of 3,750 warheads in September 2020—only 72 warheads fewer than the last number made available in September 2017 before the Trump administration reduced the US government’s transparency efforts (US State Department 2021). We estimate that the stockpile will continue to decline over the next decade as modernization programs consolidate the remaining warheads.

Following the Biden administration’s initial declassification in 2021, it has since denied successive annual requests from the Federation of American Scientists to disclose the stockpile numbers for 2021, 2022, or 2023 (Kristensen 2023d). A decision to no longer declassify these numbers not only contradicts the Biden administration’s own recent practices, but also represents a return to Trump-era levels of nuclear opacity. Such increased nuclear secrecy undermines US calls for Russia and China to increase transparency of their nuclear forces.

The US nuclear weapons are thought to be stored at an estimated 24 geographical locations in 11 US states and five European countries (Kristensen and Korda 2019, 124). The number of locations will increase over the next decade as nuclear storage capacity is added to three bomber bases. The location with the most nuclear weapons by far is the large Kirtland Underground Munitions and Maintenance Storage Complex south of Albuquerque, New Mexico. Most of the weapons in this location are retired weapons awaiting dismantlement at the Pantex Plant in Texas. The state with the second-largest inventory is Washington, which is home to the Strategic Weapons Facility Pacific and the ballistic missile submarines at Naval Submarine Base Kitsap. The submarines operating from this base carry more deployed nuclear weapons than any other base in the United States.

Implementing the New START treaty

The United States appears to be in compliance with the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) limits. Although Russia “suspended” its participation in New START in February 2023, the United States publicly declared in May 2023 that it had 1,419 warheads attributed to 662 deployed ballistic missiles and heavy bombers as of March 1st, 2023 (US State Department 2023a). The United States initially said that it voluntarily released the numbers “[i]n the interest of transparency and the US commitment to responsible nuclear conduct.” However, the United States did not continue this practice beyond that initial exchange and has not published any aggregate numbers since May 2023 (US State Department 2023a).

The United States contends that Russia’s “suspension” of New START implementation is “legally invalid” (US State Department 2023c). In response, the United States adopted four countermeasures in 2023 that it claimed were fully consistent with international law 1) no longer providing biannual data updates to Russia; 2) withholding from Russia notifications regarding treaty-accountable items (i.e. missiles and launchers) required under the treaty; 3) refraining from facilitating inspection activities on US territory; and 4) not providing Russia with telemetric information on US ICBM and SLBM launches (US State Department 2023c).

The New START warhead numbers reported by the US State Department differ from the estimates presented in this Nuclear Notebook, though there are reasons for this. The New START counting rules artificially attribute one warhead to each deployed bomber, even though US bombers do not carry nuclear weapons under normal circumstances. Also, this Nuclear Notebook counts as deployed all weapons stored at bomber bases that can quickly be loaded onto the aircraft, as well as nonstrategic nuclear weapons at air bases in Europe. This provides a more realistic picture of the status of US deployed nuclear forces than the treaty’s artificial counting rules.

Since the treaty entered into force in February 2011, the biannual aggregate data show the United States has cut its arsenal by a total of 324 strategic launchers, reduced deployed launchers by 220 and the warheads attributed to them by 381 (US State Department 2011). The warhead reduction is modest, only equivalent to about 10 percent of the 3,708 warheads remaining in the US stockpile. The 2022 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) stated that “[t]he United States will field and maintain strategic nuclear delivery systems and deployed weapons in compliance with New START Treaty central limits as long as the Treaty remains in force” (US Department of Defense 2022a, 20).

As of March 2023, the United States had 38 launchers and 131 warheads less than the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons but had 119 deployed launchers more than Russia—a significant gap that is just under the size of an entire US Air Force intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) wing. So far Russia has not sought to reduce this gap by deploying more strategic launchers but instead has increased the portion of its missiles that can carry multiple warheads.

The New START treaty has proven useful so far in keeping a lid on both countries’ deployed strategic forces. But it expires in February 2026 and if it is not followed by a new agreement, both the United States and Russia could potentially increase their deployed nuclear arsenals by uploading several hundred of stored reserve warheads onto their launchers. Additionally, if the treaty’s verification and data-exchange arrangements are not replaced, both countries will lose important information about each other’s nuclear forces. Until the treaty’s so-called “suspension,” the United States and Russia had completed a combined 328 on-site inspections and exchanged 25,017 notifications (US State Department 2022).

Nuclear Posture Reviews and nuclear modernization programs

The Biden administration’s 2022 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) was broadly consistent with the Trump administration’s 2018 NPR (albeit with minor adjustments), which in turn followed the broad outlines of the Obama administration’s 2010 NPR to modernize the entire nuclear weapons arsenal. Just like previous NPRs, the Biden administration’s NPR said the United States reserved the right to use nuclear weapons under “extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States or its allies and partners” and rejected policies of nuclear “no-first-use” or “sole purpose” (US Department of Defense 2022a, 9). Even so, the 2022 NPR notes that the United States “retain[s] the goal of moving toward a sole purpose declaration and [it] will work with [its] Allies and partners to identify concrete steps that would allow [it] to do so” (US Department of Defense 2022a, 9) (For a detailed analysis of the 2022 NPR, see Kristensen and Korda 2022).

The most significant change between the Biden and Trump NPRs was the walking back of two Trump-era commitments—specifically, canceling the proposed nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N) and continuing with the retirement of the B83–1 gravity bomb.

The Trump NPR had asserted that a SLCM-N with low-yield capability “may provide the necessary incentive for Russia to negotiate seriously a reduction of its nonstrategic nuclear weapons, just as the prior Western deployment of Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces [INF] in Europe led to the 1987 INF Treaty” (US Department of Defense 2018, 55). However, this has not proved to be the case. Furthermore, the theory that additional low-yield capabilities would somehow change Russia’s behavior seems flawed because the US arsenal already includes nearly 1,000 gravity bombs and air-launched cruise missiles, combined, with low-yield warhead options (Kristensen 2017b). Moreover, US Strategic Command has already strengthened strategic bombers’ support of NATO in response to Russia’s more provocative and aggressive behavior (see below): 46 B-52 bombers are currently equipped with the AGM-86B air-launched cruise missile and both the B-52 and the new B-21 bombers will receive the new AGM-181 Long-Range Standoff Weapon (LRSO), which will have very similar capabilities to the sea-launched cruise missile proposed by the 2018 NPR.

Furthermore, the US Navy used to have a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (the TLAM-N) but completed retirement of the system by 2013 because it was redundant and no longer needed. All other nonstrategic nuclear weapons—except gravity bombs for fighter-bombers—have also been retired because there was no longer any military need for them, despite Russia’s larger nonstrategic nuclear weapons arsenal. The suggestion that a US sea-launched cruise missile could motivate Russia to return to compliance with the INF Treaty was also flawed because Russia embarked upon its violation of the treaty at a time when the TLAM-N was still in the US arsenal; besides, the Trump administration ultimately withdrew the United States from the INF Treaty anyway. Development of a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile would violate the United States’ pledge made in the 1992 Presidential Nuclear Initiative not to develop any new types of nuclear sea-launched cruise missiles (Koch 2012, 40), and could, if deployed in the Pacific, potentially also incite China to increase its regional nuclear capabilities.

One final argument against the sea-launched cruise missile is that nuclear-capable vessels triggered frequent and serious political disputes during the Cold War when they visited foreign ports in countries that did not allow nuclear weapons on their territory. In the case of New Zealand, diplomatic relations have only recently—some 30 years later—recovered from those disputes. And Iceland recently opened its ports to non-nuclear-armed attack submarines for the first time ever. Reconstitution of a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile would reintroduce this foreign relations irritant and needlessly complicate relations with key allied countries in Europe and Northeast Asia.

The Biden administration’s NPR echoed many of these arguments, concluding that the “SLCM-N was no longer necessary given the deterrence contribution of the W76-2, uncertainty regarding whether SLCM-N on its own would provide leverage to negotiate arms control limits on Russia’s NSNW, and the estimated cost of SLCM-N in light of other nuclear modernization programs and defense priorities” (US Department of Defense 2022a, 20). The Biden administration used even stronger language against the SLCM-N in an October 2022 statement suggesting that “the SLCM-N, which would not be delivered before the 2030s anyway, is unnecessary and potentially detrimental to other priorities” (US Office of Management and Budget 2022). In its statement, the administration noted that “[f]urther investment in developing SLCM-N would divert resources and focus from higher modernization priorities for the US nuclear enterprise and infrastructure, which is already stretched to capacity after decades of deferred investments. It would also impose operational challenges on the Navy” (US Office of Management and Budget 2022). This is because to carry nuclear weapons onboard, Navy crews would require specialized training and would need to adopt strict security protocols that could operationally hinder these multipurpose vessels (Woolf 2022). Additionally, deployed nuclear sea-launched cruise missiles would take the place of more flexible conventional munitions for vessels on patrol, thus incurring a substantial opportunity cost (Moulton 2022).

Despite the Biden administration’s conclusions, however, the SLCM-N may ultimately be funded through congressional intervention. The Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) authorized nominal funding for the system and required the establishment of a program of record for the SLCM-N, even though the Biden administration’s FY 2023 budget request recommended zeroing out the system’s funding entirely (US Congress 2023). The FY 2025 NDAA continued funding of the weapon and the administration accepted it but it remains to be seen whether the SLCM-N will ultimately be fielded given funding constraints and other priorities.

The Biden administration’s NPR also continued earlier plans to retire the B83-1 gravity bomb—the last nuclear weapon with a megaton-level yield in the US nuclear arsenal—“due to increasing limitations on its capabilities and rising maintenance costs” (US Department of Defense 2022a, 20). The Trump administration had put on hold previous plans to retire the B83–1 (US Department of Defense 2018).

The complete nuclear modernization and maintenance program will continue well beyond 2039 and, based on the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate, will cost $1.2 trillion over the next three decades. Notably, although the estimate accounts for inflation (Congressional Budget Office 2017), other estimates forecast that the total cost will be closer to $1.7 trillion (Arms Control Association 2017). Whatever the actual price tag will be, it is likely to increase over time, resulting in increased competition with conventional modernization programs planned for the same period.

In 2023, multiple governmental advisory commissions published reports intended to influence US nuclear posture. The Congressionally-mandated report on “America’s Strategic Posture,” published in October 2023, included a broad range of recommendations for the United States to prepare to increase the number of deployed warheads, as well as to scale up its production capacity of bombers, air-launched cruise missiles, ballistic missile submarines, non-strategic nuclear forces, and warheads (US Strategic Posture Commission 2023). It also called for the United States to deploy multiple warheads on land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and consider adding road-mobile ICBMs to its arsenal. In contrast, the US State Department’s International Security Advisory Board report on “Deterrence in a World of Nuclear Multipolarity” advised the United States to pursue competition with Russia and China “without accelerating arms race instability or risking runaway competition” (US State Department 2023b). While neither report represents official US government policy, the Strategic Posture Commission report’s status as a bipartisan document has been particularly useful for nuclear advocates to push for additional nuclear weapons (Heritage 2023; Hudson Institute 2023; Thropp 2023).

While additional modernization programs are being discussed, the National Nuclear Security Administration, or NNSA, delivered in 2023 more than 200 modernized nuclear weapons (B61–12 bombs and W88 Alt 370 warheads) to the Department of Defense (US Department of Energy 2024).

Nuclear planning and nuclear exercises

In addition to the Nuclear Posture Review, the nuclear arsenal and the role it plays is shaped by plans and exercises that create the strike plans and practice how to carry them out.

The current strategic nuclear war plan—OPLAN 8010–12—consists of “a family of plans” directed against four identified adversaries: Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran. Known as “Strategic Deterrence and Force Employment,” OPLAN 8010–12 first entered into effect in July 2012 in response to operational order Global Citadel. The plan is flexible enough to absorb normal changes to the posture as they emerge, including those flowing from the NPR. Several updates have been made since 2012, but more substantial updates will trigger the publication of what is formally considered a “change.” The April 2019 change refocused the plan toward “great power competition,” incorporated a new cyber plan, and reportedly blurred the line between nuclear and conventional attacks by “fully incorporat[ing] non-nuclear weapons as an equal player” (Arkin and Ambinder 2022a, 2022b).

OPLAN 8010–12 also “emphasizes escalation control designed to end hostilities and resolve the conflict at the lowest practicable level” by developing “readily executable and adaptively planned response options to de-escalate, defend against, or defeat hostile adversary actions” (US Strategic Command 2012). While not new, these passages are notable, not least of which because the Trump administration’s NPR criticized Russia for an alleged willingness to use nuclear weapons in a similar manner, as part of a so-called “escalate-to-deescalate” strategy.

The Nuclear Employment Strategy published by the Trump administration in 2020 reiterates this objective: “If deterrence fails, the United States will strive to end any conflict at the lowest level of damage possible and on the best achievable terms for the United States, and its allies, and partners. One of the means of achieving this is to respond in a manner intended to restore deterrence. To this end, elements of US nuclear forces are intended to provide limited, flexible, and graduated response options. Such options demonstrate the resolve, and the restraint, necessary for changing an adversary’s decision calculus regarding further escalation” (US Department of Defense 2020, 2). This objective is not just directed at nuclear attacks, as the 2018 NPR called for “expanding” US nuclear options against “non-nuclear strategic attacks.” The Biden administration is expected to complete its guidance in 2024.

OPLAN 8010–12 is a whole-of-government plan that includes the full spectrum of national power to affect potential adversaries. This integration of nuclear and conventional kinetic and non-kinetic strategic capabilities into one overall plan is a significant change from the strategic war plan of the Cold War that was almost entirely nuclear. In 2017, former US Strategic Command commander Gen. John Hyten explained the scope of modern strategic planning by saying:

I’ll just say that the plans that we have right now, one of the things that surprised me most when I took command on November 3 was the flexible options that are in all the plans today. So we actually have very flexible options in our plans. So if something bad happens in the world and there’s a response and I’m on the phone with the Secretary of Defense and the President and the entire staff, which is the Attorney General, Secretary of State, and everybody, I actually have a series of very flexible options from conventional all the way up to large-scale nuke that I can advise the president on to give him options on what he would want to do …

The last time I executed or was involved in the execution of the nuclear plan was about 20 years ago, and there was no flexibility in the plan. It was big, it was huge, it was massively destructive, and that’s all there. We now have conventional responses all the way up to the nuclear responses, and I think that’s a very healthy thing. (Hyten 2017)

The 2022 Nuclear Posture Review and 2023 Strategy for Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction reaffirm the importance of flexibility, integration, and tailored plans (US Department of Defense 2023f). To practice and fine-tune these plans, the armed forces conducted several nuclear-related exercises in 2023. In October 2023, Air Force Global Strike Command conducted exercise Prairie Vigilance, an annual nuclear bomber exercise at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota, which practiced the 5th Bomb Wing’s B-52 strategic readiness and nuclear generation operations (US Air Force 2023a).

The Vigilance exercises normally lead up to Strategic Command’s annual week-long Global Thunder large-scale exercise toward the end of the year, which “provides training opportunities that exercise all US Strategic Command mission areas, with a specific focus on nuclear readiness” (US Strategic Command 2021a). The exercise was most recently conducted in April 2023 at Minot AFB after being delayed in 2022 (US Air Force 2023d).

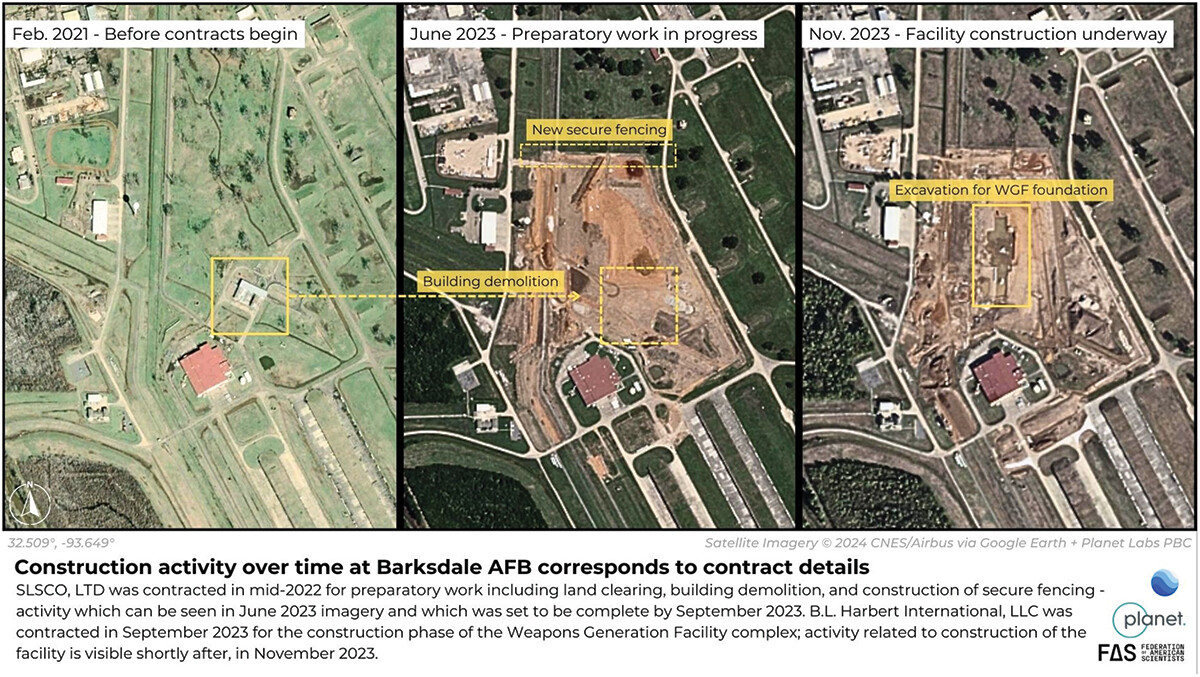

These exercises coincide with steadily increasing US bomber operations in Europe since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014 and again in 2022. Before that, one or two bombers would deploy for an exercise or airshow. But since then, the number of deployments and bombers has increased, and the mission has changed. Very quickly after the Russian annexation of Crimea, the US Strategic Command increased the role of nuclear bombers in support of the US European Command (Breedlove 2015), which, in 2016, put into effect a new standing war plan for the first time since the Cold War (Scapparotti 2017). Before 2018, the bomber operations were called the Bomber Assurance and Deterrence missions but have been redesigned as Bomber Task Force missions to bring a stronger offensive capability to the forward bases. Whereas the mission of Bomber Assurance and Deterrence was to train with allies and have a visible presence to deter Russia, the mission of the Bomber Task Force is to move a fully combat-ready bomber force into the European theater. “It’s no longer just to go partner with our NATO allies or to go over and have a visible presence of American air power,” according to the commander of the 2nd Bomb Wing. “That’s part of it, but we are also there to drop weapons if called to do so” (Wrightsman 2019). These changes are evident in the types of increasingly provocative bomber operations over Europe, in some cases very close to the Russian border (Kristensen 2022a). In October 2023, for example, a B-52 bomber from Barksdale AFB in Louisiana participated in NATO’s annual nuclear exercise Steadfast Noon, and in March 2023 a nuclear-capable B-52 cut south only a few kilometers from the Russian sea border and then flew south near Kaliningrad (Kristensen 2023a; NATO 2023).

These changes are important indications of how US strategy has changed in response to deteriorating East-West relations and the new “great power competition” and “strategic competition” strategy promoted by the Trump and Biden administrations, respectively. They also illustrate a growing integration of nuclear and conventional capabilities, as reflected in the new strategic war plan. B-52 Bomber Task Force deployments typically include a mix of nuclear-capable aircraft and aircraft that have been converted to conventional-only missions. With Sweden joining NATO, US strategic bombers now routinely operate over Swedish territory: In August 2022, for example, two B-52s—one version that is nuclear-capable and one that is de-nuclearized—overflew Sweden, the first overflight since it applied for NATO membership in May 2022 (Kristensen 2022c). On September 21, 2022—the very same day Russian President Vladimir Putin threatened to use nuclear weapons to defend newly annexed regions of Ukraine (Faulconbridge 2023)—four B-52s in Europe took off from the RAF Fairford Station in the United Kingdom and returned to the United States, two of them via northern Sweden. At the same time, their wing at Minot AFB in North Dakota was in the middle of the Prairie Vigilance nuclear exercise. Such close integration of nuclear and conventional bombers into the same task force can have significant implications for crisis stability, misunderstandings, and the risk of nuclear escalation because it could result in overreactions and misperceptions about what is being signaled.

Additionally, since 2019, US bombers have been practicing what is known as an “agile combat employment” strategy by which all bombers “hopscotch” to a larger number of widely dispersed smaller airfields—including airfields in Canada—in the event of a crisis. This strategy is intended to increase the number of aimpoints for a potential adversary seeking to destroy the US bomber force, therefore raising the ante for an adversary to attempt such a strike and increasing the force’s survivability if it does (Arkin and Ambinder 2022a).

Land-based ballistic missiles

The US Air Force (USAF) operates 400 silo-based Minuteman III ICBMs and keeps “warm” another 50 silos to load stored missiles if necessary, for a total of 450 silos. Land-based missile silos are divided into three wings: the 90th Missile Wing at F. E. Warren Air Force Base in Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming; the 91st Missile Wing at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota; and the 341st Missile Wing at Malmstrom Air Force Base in Montana. Each wing has three squadrons, each with 50 Minuteman III silos collectively controlled by five launch control centers. We estimate there are up to 800 warheads assigned to the ICBM force, of which about half are deployed (see Table 1).

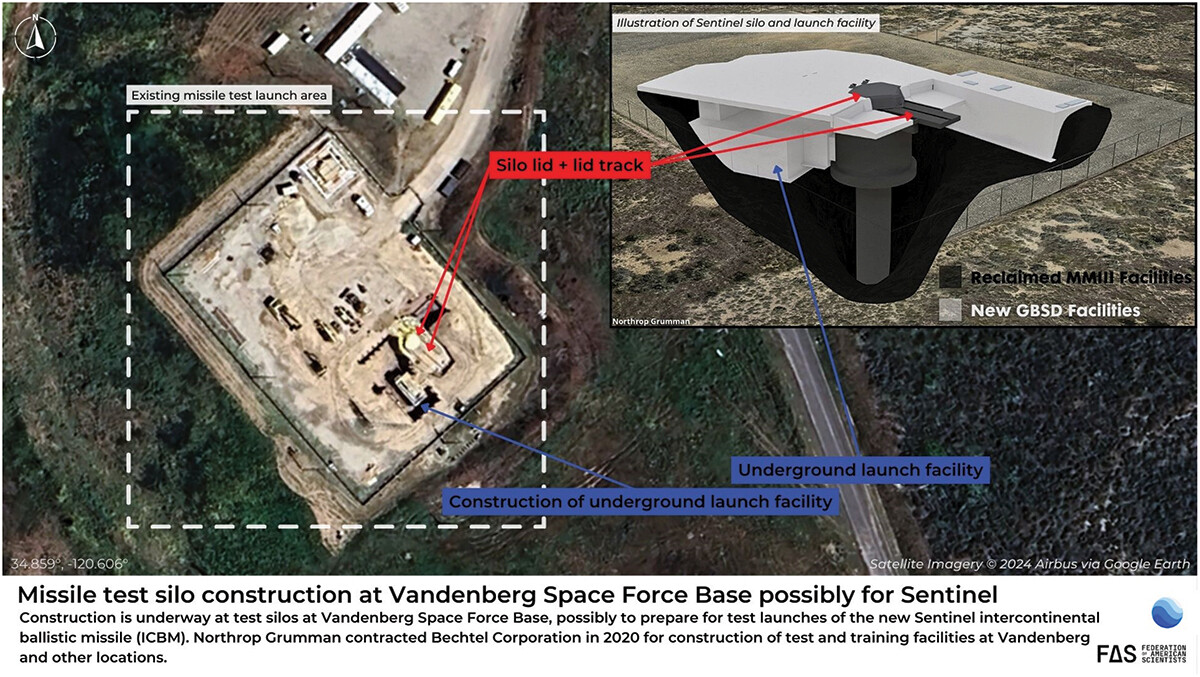

The 400 deployed Minuteman IIIs carry one warhead each, either a 300-kiloton W87/Mk21 or a 335-kiloton W78/Mk12A. ICBMs equipped with the W78/Mk12A, however, could technically be uploaded to carry two or three independently targetable warheads each, for a total of 800 warheads available for the ICBM force. The USAF occasionally test-launches Minuteman III missiles with unarmed multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) to maintain and signal the capability to reequip the Minuteman III missiles with additional reentry vehicles, if desired. The most recent such test occurred on September 6, 2023, when a Minuteman III equipped with three test reentry vehicles was launched from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California and flew approximately 4,200 miles to the US ICBM testing ground at the Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands (US Air Force 2023e).

Although the Minuteman III was initially deployed in 1970, it has been modernized several times, including in 2015, when the missiles completed a multibillion-dollar, decade-long modernization program to extend their service life until 2030. The modernized Minuteman III missiles were referred to by Air Force personnel as “basically new missiles except for the shell” (Pampe 2012).

Part of the ongoing ICBM modernization program involves upgrades to the Mk21 reentry vehicles’ arming, fuzing, and firing system at a total cost of nearly $1 billion (US Department of Defense 2023c, 32). The publicly stated purpose of this refurbishment is to extend the vehicles’ service lives, but the effort appears to also involve adding a “burst height compensation” to enhance the targeting effectiveness of the warheads (Postol 2014). A total of 743 fuze replacements—including all necessary units for the development, qualification, certification, fielding, aging, and replenishment of the fuzes—are planned to be delivered for deployment on the Minuteman IIIs as well as their replacement missile—LGM-35 Sentinel—by the end of FY26 (US Department of Defense 2023a). A cost-projection overrun of the fuze integration program unit cost triggered a breach of the Nunn-McCurdy Act in September 2020 but is expected to begin full-rate production in FY 2024 (Reilly 2021; US Department of Defense 2023c). As part of the Mk21A program, Lockheed Martin was awarded a sole source contract in October 2023 amounting to just under $1 billion for the engineering and manufacturing of the new reentry vehicle (US Department of Defense 2023b). These modernization efforts complement a similar fuze upgrade underway to the Navy’s W76–1/Mk4A warhead.

Early acquisition activities for a Next Generation Reentry Vehicle (NGRV) began in FY24. The NGRV will be integrated into the new Sentinel ICBM to bolster its payload suite and will be capable of carrying both current and future warheads (US Air Force 2023f, 589).

The Air Force’s FY24 budget for ICBM Reentry Vehicles Research Development, Test & Evaluation Programs increased significantly from the previous President’s Budget due to changes to the Payload Reentry System requirements, which cost an extra $43.4 million, as well as the need to add another flight test due to a failed flight test in July 2022, which will cost over $48 million. In addition, NGRV funding was accelerated to begin early acquisition activities in FY24, adding $15.5 million to the FY24 budget. The total program cost for ICBM reentry vehicle development in FY24 is just over $475 million and will increase up to $864 million by FY28 (US Air Force 2023f, 589).

While the Air Force insists that “there is no backup plan for Sentinel,” it appears that it would be technically possible to conduct a second life-extension of the Minuteman III missile before it would have to be retired and replaced (Clark 2019; Heckmann 2023). A July 2022 environmental impact assessment revealed that the Air Force did consider such a life extension as well as three other options, including deploying a “[s]mall ICBM […] with lower procurement costs and enhanced accuracy;” working with “a private spacecraft company” to deploy commercial launch vehicles equipped with nuclear-capable reentry vehicles; and converting the existing Trident II D5 sea-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) to be deployed in land-based silos. However, the Air Force ultimately eliminated these options because they did not meet what it called its “selection standards,” which include criteria such as sustainability, performance, safety, riskiness, and capacity for integration into existing or proposed infrastructure (US Air Force 2022d). Instead, the Air Force opted to purchase a whole new generation of ICBMs known by its programmatic name—the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD)—until it was officially named the LGM-35A Sentinel in April 2022 (US Air Force 2022a).

Non-governmental experts, including those conducting Department of Defense-sponsored research, have questioned the Pentagon’s procurement process and lack of transparency regarding its decision to pursue the Sentinel option over other potential deployment and basing options (Dalton et al. 2022, 4). Moreover, it is unclear why an enhancement of ICBM capabilities would be necessary for the United States. For instance, any such enhancements would not mitigate the inherent challenges associated with launch-on-warning, risky territorial overflights, or silo vulnerabilities to environmental catastrophes or conventional counterforce strikes (Korda 2021). Additionally, even if adversarial missile defenses improved significantly, the ability to evade missile defenses lies with the payload—not the missile itself. By the time an adversary’s interceptor would be able to engage a US ICBM in its midcourse phase of flight, the ICBM would already have shed its boosters, deployed its penetration aids, and be guided solely by its reentry vehicle—which can be independently upgraded as necessary. For this reason, it is not readily apparent why the US Air Force would require its ICBMs to have capabilities beyond the current generation of Minuteman III missiles; the Air Force has yet to publicly explain why.