- Market Segmentation in Tourism (What It Is & Why It Matters)

Pete Sherwood , Director of Content Strategy

Pete Sherwood

Director of content strategy.

Don’t let the ever-present hat fool you (he took it off for this one photo), Pete is "all business" when it comes to taking websites from good to great. Pete writes compelling copy for users as well as search engines, and while he's sensitive about his overuse of em-dashes, he's constantly churning out succinct, targeted copy for clients in a variety of industries.

- eCommerce Content Marketing Tips (That Work)

- E-Commerce Use Case: Corinthian Marine

- E-commerce: Market segmentation strategies can grow your sales

- The Pillars of Branding for Credit Unions

- Why Hire a Copywriter

- The Digital Patient Journey: Turning searches into conversions

- Medical on Mobile: Why Responsive and Mobile First Design Are Vital to the Healthcare Industry

March 22, 2023 | Reach an Audience

Originally published April 11, 2017 Updated March 26, 2023

As the tourism industry continues to advance, competition among businesses intensifies. To excel, you must understand your customers’ diverse needs and preferences.

This is where travel market segmentation comes in. This process divides a larger market into smaller groups of consumers with similar needs and characteristics.

Market segmentation is essential for travel and tourism businesses to effectively reach and engage with their target audience.

By identifying specific travel segments, such as solo travelers, adventure seekers, or luxury travelers, you can tailor your offerings and marketing messages to meet their unique needs.

In fact, a report by McKinsey & Company shows 71% of consumers expect companies to deliver personalized interactions .

This report indicates the increasing significance of market segmentation in the tourism industry. Companies that excel at demonstrating customer intimacy generate faster revenue growth rates than their peers.

In this blog post, I’ll explore the importance of market segmentation in tourism, why it’s important, and how you can use it to improve your marketing strategy.

What Is Market Segmentation in Tourism?

Market segmentation in tourism is the process of dividing the market into smaller groups of consumers with similar needs or characteristics . This helps tourism businesses tailor their offerings and marketing messages. Travel market segmentation also increases customer satisfaction and loyalty.

Why Is Market Segmentation Important in the Tourism Industry?

Travel market segmentation is a crucial strategy in the tourism industry. Travel segments divide customers into distinct groups based on their needs, interests, behaviors, and demographics.

Travel segments also help businesses tailor their marketing efforts and develop targeted products and services for each group. As a result, travel and tourism companies can maximize revenue and customer satisfaction.

Here are some key reasons why market segmentation is important in the tourism industry:

Helps businesses understand their customers : By segmenting the market, you can better understand your customers and create more personalized experiences and products.

Allows for targeted marketing : Customer segments help you create marketing messages and campaigns tailored to each unique group. This can increase the effectiveness of your marketing efforts and improve customer engagement.

Increases customer satisfaction : Offering products and services customized to your customers will likely satisfy their experience. This can lead to repeat business and positive word-of-mouth.

Boosts revenue : Creating targeted products and services that appeal to specific customer segments can increase revenue. You can attract and retain more customers, which improves profitability.

What Are the 4 Types of Traveler Segmentation?

There are several different ways to segment the travel market. The four main tourism market segments include:

- Demographic segmentation in tourism : Dividing customers based on age, gender, income, education, and other demographic factors.

- Geographic segmentation in tourism : Segmenting customers based on location, such as country, region, or city.

- Psychographic segmentation in tourism : Dividing customers based on their lifestyle, interests, values, and personality traits.

- Behavioral segmentation in tourism : Segmenting customers based on their behaviors and actions, such as travel frequency, spending habits, and travel motivations.

Using these travel segments, you can develop targeted marketing strategies, improve customer satisfaction, increase loyalty, and boost revenue.

For instance, a business that focuses on adventure travel may target customers with a high interest in outdoor activities and a willingness to take risks.

Some popular segment names for the travel and tourism industry are escapists, learners, planners, and dreamers.

What Are Examples of Market Segmentation in Tourism?

Here are five brief tourism market segmentation examples. They illustrate how businesses can tailor their offerings to specific customer needs.

- Hotel targeting business travelers by offering conference rooms and fast Wi-Fi.

- Tour company targeting adventure seekers by offering hiking and extreme sports packages.

- Cruise line targeting families by offering kid-friendly activities and childcare services.

- Luxury resort targeting customers with a high income and a preference for exclusive amenities and experiences.

- A destination marketing organization targeting retirees by promoting cultural events and attractions.

Businesses that leverage tailored travel segments gain a competitive edge in the tourism industry.

Seize the (Micro) Moment in Travel Market Segmentation

Market segmentation in tourism requires you to think critically about your target audience and how they move through the customer journey.

Often, tourism and travel market segments are created by one, or a combination, of the following:

- Age / life stage (e.g., millennial, retiree)

- Socioeconomic status

- Type of travel (e.g., business, leisure, extended stay)

With online research easier and more portable than ever, we like to think about travel segments a little differently.

Travel brands and destination marketers should consider the moments your potential customers may jump online from their phone or computer—as the biggest marketing opportunity.

While the who still matters when you’re trying to reach an audience—the when is more vital than ever.

For example, think about how you planned your last vacation. If you were like most, you bounced back and forth between dreaming about and loosely planning your next getaway—zooming in on a destination and quickly bouncing around in search of inspiration only to zoom out and consider all the options yet again.

This quick spurt of research to answer an immediate need (usually turning to a search engine) has been coined “a micro-moment” by Google.

Such micro-moments represent a huge opportunity for destination marketing organizations and are the key to attracting and earning a savvy traveler’s consideration.

Often, we pull in focus groups to test our theories on user motivation and needs. From on-paper prototypes and discussion groups to high-fidelity wireframes and user-experience videos—we pick from our bag of user-testing methods to ensure content and calls-to-action are placed in the best places possible.

How to Use Travel Segments in Your Marketing Strategy

What if your brand or location could be in front of your potential customers during the exact moments they are dreaming about getting away, planning their visit, and eventually booking their vacation? What content should you create at what moments?

Knowing how to leverage travel market segmentation and the power of micro-moments is the key to upping your travel industry marketing game.

It’s how you keep your messaging laser focused and your audience satisfied. As a result, your travel or tourism company will see increased customer satisfaction, loyalty, and revenue!

Market Segmentation in Tourism FAQ

Answers to common questions about tourism market segmentation.

Why Do We Segment the Tourism Market?

The travel market is far too large and diverse to reach effectively in one fell swoop. Tourism marketers use segmentation to understand customer needs better and allocate marketing dollars effectively.

Effective travel market segmentation is based on extensive quantitative research focusing on large numbers of people. Then grouping them based on shared characteristics such as:

- Demographics

- Behavioral patterns

- Cognition ratings

Once identified, these groups are referred to as particular segments. You can target them with specific product offerings, services, and tailored marketing messages.

What Are the Components of the Tourism Industry?

There are six main components of tourism, each with sub-components. The six components of travel and tourism include attractions, activities, accessibility, accommodation, amenities, and transportation.

Travel Segments vs Personas: What’s the Difference?

Personas are used to encourage a design for real people with real needs. They break down the user’s context, needs, motivations, and pain points on a personal basis.

Travel segments aim to pinpoint and measure the size of different groups at a high level.

Market segmentation isn’t persona research. Sure, they’re very similar tools that group current and potential customers into manageable buckets. However, you can’t create a detailed buyer persona without first diving into market research.

Nonprofit Web Design Best Practice: Increasing Donations

B2b content marketing trends, four tips for marketing to older adults, hire gravitate. get results., web design & development.

We deliver compelling digital experiences to drive brands forward, engage target audiences, and drive results.

Digital Marketing

We evolve and continually enhance your digital presence to drive traffic and improve conversions.

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, market segmentation analysis in tourism: a perspective paper.

Tourism Review

ISSN : 1660-5373

Article publication date: 27 June 2019

Issue publication date: 20 February 2020

This paper discusses the dos and don'ts of market segmentation analysis. Market segmentation analysis is younger than the journal Tourism Review , but nevertheless has a rich history in tourism research and continues to be extensively used by both tourism researchers and industry.

Design/methodology/approach

After a brief overview of the origins of market segmentation analysis and its uptake in tourism, a number of key considerations are discussed, which are critical to ensuring that practically useful and reliable market segments emerge from the analysis.

Do accept that market segmentation is exploratory. Do spend a lot of time ensuring you collect high-quality data. Don’t use ordinal data. Don’t use correlated variables. Do ensure your sample size is large enough. Don’t use factor-cluster analysis. Do conduct data structure analysis. Don’t complicate things.

Originality/value

This is a perspective study; it offers a concise discussion of key issues in market segmentation analysis and directs the interested reader to resources where they can learn more about each of these issues.

- Cluster analysis

- Sample size

- Market segment

- Market segmentation analysis

Dolnicar, S. (2020), "Market segmentation analysis in tourism: a perspective paper", Tourism Review , Vol. 75 No. 1, pp. 45-48. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-02-2019-0041

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

- Current affairs

THR's opinion

The basics of tourism market segmentation.

- Who is your client?

- Where is your client located?

- What is your client interested in?

- How would you introduce your product to that client?

- Why would certain segments be interested or not interested in your products?

- The market is a set of separate segments, reflecting the variations in demand of different categories of consumers under the influence of various factors.

- Your marketing success will highly depend on your ability to reach the audience you’re marketing to with a targeted marketing message, so make sure to get clear understanding of their persona.

- It is necessary to differentiate products and marketing methods for each market segmentation, based on previous analysis of the demand and common characteristics.

Would you like to request the advice of our experts?

Last tweets.

The Vital Role of Market Segmentation in the Tourism Industry

What is Market Segmentation in the Tourism Industry?

Why is market segmentation important in tourism, what are the 4 segments of the tourism industry, tourism market segmentation examples, frequently asked questions (faq).

The tourism industry is an ever-growing and competitive landscape , presenting both challenges and opportunities for businesses operating within it. This is where market segmentation comes in handy.

In this blog post, we will discuss what market segmentation is, the importance of market segmentation in the tourism industry, and how online travel agencies can benefit from it.

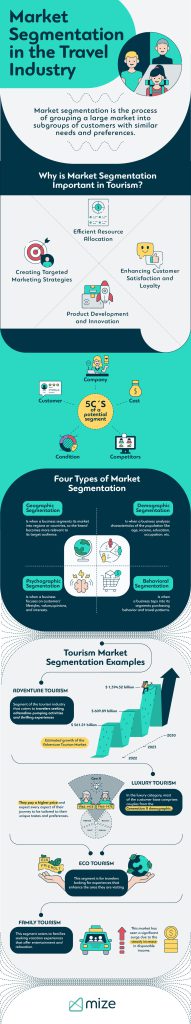

Market segmentation in the tourism industry is the process of grouping a large market into subgroups of customers with similar needs and preferences.

Definition: Dividing a market who have different needs into groups that have similar needs.

The main goal of segmentation is to classify consumers based on shared interests. This results in content that gets seen, messaging that gets heard, and products and services that get sold.

The Role of Market Segmentation for Online Travel Agencies (OTAs)

Segmentation allows online travel agencies to cater to different types of travelers with unique and diverse interests, lifestyles, preferences, aspirations, expectations, and habits.

The challenge OTAs and those within the tourism sector face is that they are all selling the exact same product. For example, if a traveler wants to say at the Four Seasons Resort in Dubai, they can book directly or via Booking.com, Hotels.com, and Expedia.

Companies that cannot differentiate themselves in the market become interchangeable with similar ones . Consequently, customers base their purchasing decisions solely on the cost of the product or service, leading to decreased profit margins.

When you segment-specific markets, you stop competing over price and start competing over value.

The Benefits of Effective Market Segmentation

There are several benefits of effective market segmentation for both the end user and online travel agencies.

The Benefits of Effective Market Segmentation for End Users

- Products and services are consumer-centric

- Segments feel seen and heard

- Consumer needs exceed expectations

- Improve travel experience

The Benefits of Effective Market Segmentation for OTAs

- Targeting the right consumers

- Offer personalized travel products and services

- Identify new and unmet needs

- Identify unexplored segments

- Differentiate from the competition

1. Creating Targeted Marketing Strategies

Market segmentation enables OTAs to develop more effective marketing strategies that attract and retain customers. This is because segmentation allows them to target different customer clusters with tailored offers and messages that burn through the noise as opposed to cookie-cutter campaigns.

Backpackers and business travelers have different interests, just as families and couples on holiday have different interests. Once you have identified your segment, you can target them based on what interest them.

One simple strategy when it comes to email marketing is to segment your email list based on buyer personas. This way, you can customize your messaging to address their specific interests and needs instead of sending the same email to everyone.

2. Efficient Resource Allocation

The more effective marketing strategies become, the more efficient businesses become at allocating their resources. This is because they stop wasting resources on irrelevant products and services that do not appeal to their customer base because they know exactly who their customers are, what they want, and how to target them.

A brand that knows who their customer is can create products and services that their customers want and tailor their messaging to attract the people most likely to purchase them.

This means businesses can allocate their resources more efficiently by focusing on what their customers actually want and need instead of what they ‘think’ they want and need.

3. Product Development and Innovation

Market segmentation helps businesses identify their customer’s needs and preferences, enabling them to develop and alter their products and services to meet their expectations. OTAs can create segment-specific offers and packages based on these insights.

Once you have chosen your specific segment or segments, it’s important to tailor your product to the unique characteristics of that segment . For example, offering a breakfast package for family travelers or a couple’s package for honeymooners.

Unique pricing options or personalized value add-ons can be developed for each segment. Price discrimination is a selling strategy OTAs can use to charge different rates to different customers for the same product or service.

For example, for hotel rooms, an OTA can:

- Sell at a higher rate based on what customers are willing to pay

- Sell at a lower rate based on what customers are willing to pay

The luxury travel segment has a higher tolerance for spending more money on their travel experiences and services. While the family travel segment is more likely to focus on finding the best deals or trying to get the most out of their money.

This can be key in identifying what price will make them jump at the opportunity and what price will make them run for the hills.

4. Enhancing Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty

The main goal of segmentation is to better serve the customer. As a result, businesses are better equipt to meet customer needs and expectations. Consequently, leading to an increase in customer satisfaction and loyalty.

By creating target marketing campaigns that resonate with prospects and customers, allocating resources efficiently, and developing products and services that meet the needs of each segment , businesses can deliver a higher level of customer satisfaction that results in repeat business and positive word-of-mouth.

For example, when you link the expectations and needs of your customers to the tour packages you create and sell , you’re customers are more likely to experience greater satisfaction.

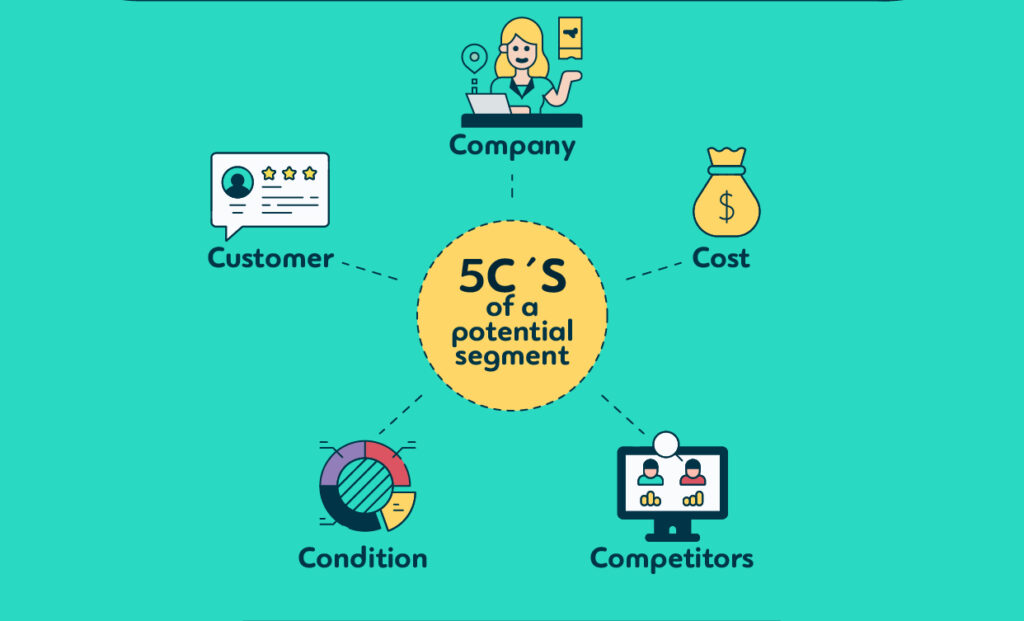

To evaluate the potential of a segment, you can review 5C’s:

It’s important to identify whether the segment you would like to choose is a viable option. As while some segments may seem like a fit, they might not provide the type of scalability you desire for your business, or they might be too costly to acquire. Let’s take a look at several factors to take into account.

- Customer: Is the chosen segment ‘attractive’ in terms of profitability? (aka how much are they willing to pay)

- Condition: How big is the market size and growth rate? (market potential)

- Cost: How much does it cost to reach the chosen segment? (customer acquisition cost)

- Company: Is this segment compatible with the company’s objectives, capabilities, and resources? (company/segment fit)

- Competitors: Who are the main competitors? ( Global OTA market share )

Now that we understand why market segmentation is so important, let’s take a look at the main segments of market segmentation.

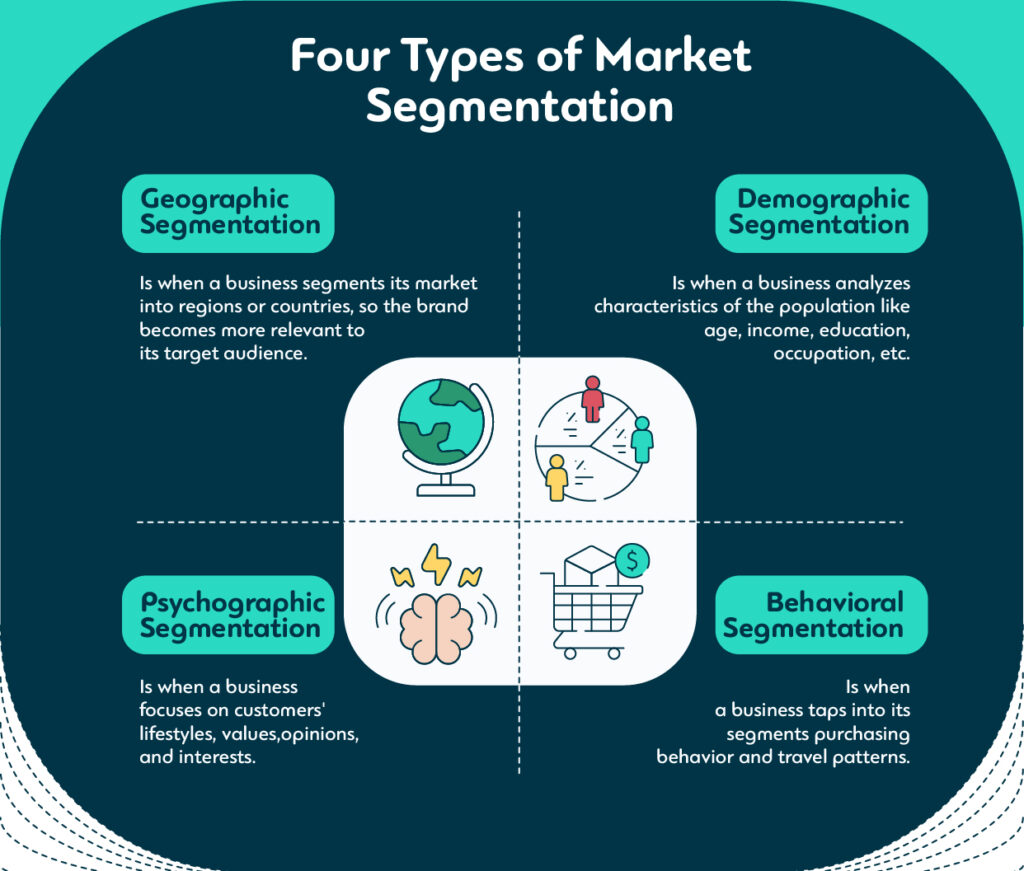

The tourism industry has four main segments, which involve identifying and targeting specific customers and categorizing them according to their geographic, demographic, psychographic, and behavioral characteristics.

1. Geographic Segmentation

Geographic segmentation is when a business segments its market into regions or countries. This can help them understand where their target audience comes from so they can tailor their marketing campaigns and messages accordingly.

Segmentation by geographic location makes a brand more relevant to its target audience , and its resources get allocated more efficiently.

For example, according to Google Travel Insights , France has The United Kingdom, The United States, and Italy as their top 3 sources of inbound demand. OTAs and local businesses in France can use this knowledge to help them better understand the people visiting their destination and buying their products and services.

2. Demographic Segmentation

Demographic segmentation is when a business analyzes the characteristics of the population. For example, age, income, education, occupation, and several other factors.

These factors can help you fine-tune your marketing strategies to relate to that chosen segment. Just like consumer behavior changes, it does the same as we age. Similarly, those with similar income levels will also seek out similar travel experiences.

For example, those traveling as young adults will expect a different experience than seniors. One group is more likely to want to say at a hostel and backpack, while the other group would prefer to have their own room with a little bit more luxury.

This type of data can be used to determine the market size and potential of the demographic segment chosen. One key demographic that travel companies should focus on targeting is Gen Z. This generation consists of late teenagers to early adults who are known to be the largest and most ethically diverse generation in the U.S. and have grown up online.

3. Psychographic Segmentation

Psychographic segmentation is when a business focuses on customers’ lifestyles, values, opinions, and interests. This helps companies to identify different customer personalities and create more targeted marketing messages that resonate.

Psychographic segmentation allows brands to tap into the emotional triggers and pain points that make people buy. This type of data can be invaluable in understanding the customer journey your segmented audiences takes from beginning to end.

This data informs how a company decides to market itself and communicate with its audience. For example, if an OTA wants to market to Gen Z, it will differ from how they market to millennials or boomers.

4. Behavioral Segmentation

Behavioural Segmentation is when a business taps into its segments purchasing behavior and travel patterns. Brands can group behavior based on seasonality, frequency of purchases or trips, and the amount spent on travel-related products and services.

For example, many European countries can expect increased demand for travel to the region in the summer months. OTAs can use this knowledge to forecast demand surges, manage inventory supply and price their products accordingly.

Additionally, this can guide the types of promotional activities marketed . For example, in the summer months, travel agencies can create summer travel deals for their target audience to take advantage of.

The four segments are often used in tandem when planning out marketing campaigns. For example, an OTA creating an Ads campaign will likely target a specific segment that lives in a particular area with unique interests, values, and behaviors.

The data they collect above can help them target those more likely to buy instead of a broader audience that may not be interested in their offer. This allows the OTA to save money, reach more people with the right message, and increase their ROI.

Tourism markets can be segmented into groups more likely to buy a certain type of holiday or experience. Many types of travel agencies are available, categorized based on several factors . Depending on the type of travel agency operated and the segment chosen.

These agencies may offer or specialize in certain kinds of trips , such as adventure tourism, luxury tourism, eco-tourism, and family tourism. We’ll take a deeper dive into each type below.

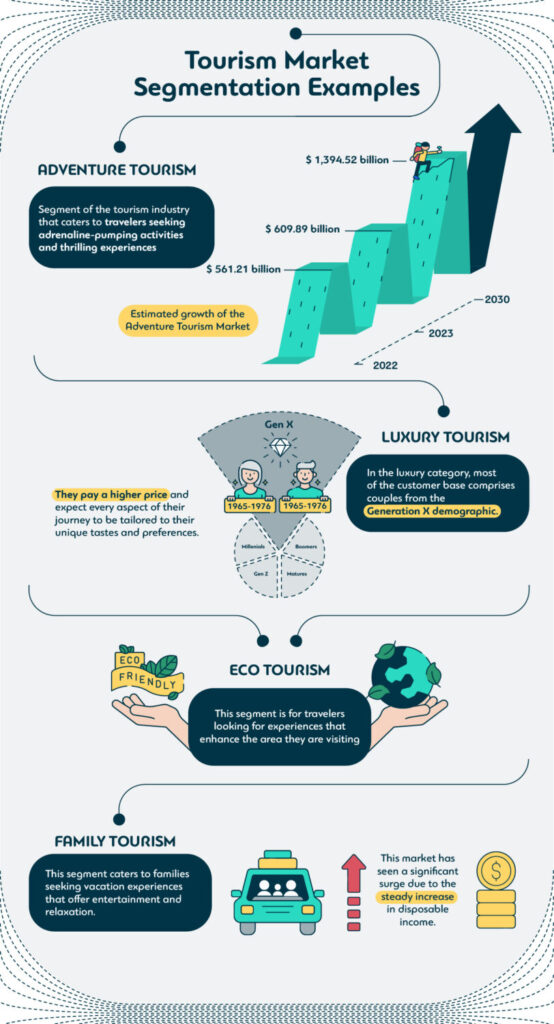

Case Study 1: Adventure Tourism

Adventure tourism is a growing segment of the tourism industry. This segment caters to travelers seeking adrenaline-pumping activities and thrilling experiences , such as skydiving, scuba diving, and mountain climbing.

Adventure tourism is usually associated with outdoor activities and adventure sports but also includes cultural activities such as trekking through remote villages. This often leads travelers to accommodations in tents or budget-friendly places.

The estimated size of the Adventure Tourism Market globally was around $USD 561.21 billion in 2022 and $USD 609.89 billion in 2023 . If current trends continue, experts predict it will reach a whopping $1,394.52 billion by 2030.

Through market segmentation, businesses can identify adventure-seeking customers they currently serve or want to serve and create travel products and packages around their interests.

Traveling allows people to leave their comfort zones and experience the thrill of the unknown . From discovering ancient ruins in the depths of the Amazon rainforest to swimming with sharks in South Africa, adventure tourism offers unforgettable experiences.

Case Study 2: Luxury Tourism

Luxury tourism is a high-end segment that caters to travelers seeking luxurious accommodations, services, and experiences.

Accommodation options in this segment are often high-end hotels, resorts, or private villas. They are known for their lavish amenities, stunning decor, and exceptional services.

In the luxury category, most of the customer base comprises couples from the Generation X demographic. The customers in this category have elevated standards compared to others. Given that they pay a higher price, they expect every aspect of their journey to be tailored to their unique tastes and preferences.

Case Study 3: Ecotourism

Ecotourism is a niche segment that caters to environmentally-conscious travelers seeking sustainable travel experiences.

Tourism of this kind is centered around awareness and preservation. Ecotourism involves responsible travel that carefully conserves, manages, and protects the environment and the local population’s well-being.

Travelers are looking for experiences that enhance the area they are visiting by participating in activities involving planting trees or supporting the local community.

Online travel agencies have been leveraging ecotourism in their marketing strategies to attract travelers looking for sustainable experiences. For example, hotels and resorts use eco-friendly materials, energy conservation methods, and green products to be more sustainable.

Case Study 4: Family Tourism

Family tourism is a segment that caters to families seeking vacation experiences that offer entertainment and relaxation.

Family-friendly destinations offer various activities and attractions for different age groups and interests.

Many hotels offer spacious family suites or interconnected rooms that can easily accommodate larger groups. These accommodations often provide amenities like swimming pools, kids’ clubs, babysitting services, and entertainment.

The family tourism market has seen a significant surge due to the steady increase in disposable income. Nowadays, tourism is no longer considered a luxury but a must-have for families .

The travel industry is one of the most competitive industries in the world. Segmentation is a powerful tool that helps online travel agencies understand their target market’s unique needs and preferences , allowing them to better serve their segment-specific markets.

This is particularly crucial for online travel agencies, which must differentiate themselves from their competitors by offering personalized services that cater to their target audience’s unique interests and expectations.

Online travel agencies can effectively use market segmentation data to identify customer needs, create targeted marketing campaigns, focus product development priorities, and inform pricing decisions. Market segmentation data can be implemented to create more target marketing strategies as OTAs now know who they are talking to. They can efficiently allocate their resources to the tasks and activities they now will gain a greater ROI. Additionally, they can use this data to improve their current and future product offerings.

Some common challenges in implementing market segmentation in the tourism industry include a lack of data and resources. Obtaining customer insights and data can be a lengthy process. However, there are tools and resources that OTAs can use to gather the insights they need to make informed decisions, such as Google travel insights and customer interviews. Another challenge is a lack of understanding of customer segments and needs. This is because consumer needs and preferences are constantly changing. OTAs need to stay on top of trends and changes to ensure their segment’s needs are still being met.

Online travel agencies can adapt their market segmentation strategies in response to changing customer preferences and market trends by regularly monitoring changes in customer needs, updating the data used for analysis, and testing new tactics. OTAs can review their market segmentation strategies every six months to a year to ensure they are still consistent with current trends and expectations.

Yes, market segmentation can help online travel agencies manage crises. Many OTAs had no choice but to implement new strategies during the pandemic. For example, as travel restrictions loosened and people could start traveling again, there was a lot of concern about getting stuck in a foreign country or being unable to get a refund if anything went wrong. Specifically, behavioral segmentation helps understand consumers’ pain points and how you can cater to them. In the case of the pandemic, many businesses implemented flexible booking policies, such as free cancellation or no change fees.

Online travel agencies should consider targeting emerging market segments in the tourism industry. Travelers are increasingly seeking out unique and immersive experiences when they travel post-pandemic. There has been a rise in the popularity of niche tourism, such as eco-tourism, wellness tourism, culinary tourism, and voluntourism. Additionally, millennials, Gen Z, solo travelers, family vacationers, digital nomads, and adventure seekers have recently gained more popularity. These segments represent higher engagement and loyalty with travel brands, offering unique opportunities for differentiated experiences and services.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Yay you are now subscribed to our newsletter.

Cristóbal Reali, VP of Global Sales at Mize, with over 20 years of experience, has led high-performance teams in major companies in the tourism industry, as well as in the public sector. He has successfully undertaken ventures, including a DMO and technology transformation consulting. In his role at Mize, he stands out not only for his analytical and strategic ability but also for effective leadership. He speaks English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian. He holds a degree in Economics from UBA, complementing his professional training at Harvard Business School Online.

Mize is the leading hotel booking optimization solution in the world. With over 170 partners using our fintech products, Mize creates new extra profit for the hotel booking industry using its fully automated proprietary technology and has generated hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue across its suite of products for its partners. Mize was founded in 2016 with its headquarters in Tel Aviv and offices worldwide.

Related Posts

Opening Up to New Markets While Maintaining the Brand

8 min. Case study of adapting the Mize brand for the East Asia market Making a cultural adjustment – finding the balance between global and local The process of growing globally can be very exciting and, at the same time, challenging. Although you are bringing more or less the same products and vision, the way […]

Travel Niche: What It Is, How to Leverage It, Case Studies & More

14 min. Niche travel is one of the few travel sectors that have maintained their pre-COVID market growth. By catering to specific traveler segments, niche travel developed products around adventure travel, eco-tourism, LGBTQ+ travel, and wellness retreats. Take adventure tourism as only one segment of the niche tourism market. In 2021, it reached 288 billion […]

4 Lessons You Can Learn From the Best Tourism Campaigns

13 min. Businesses in the tourism industry rely heavily on marketing to generate leads and boost conversion rates. Tourism marketing is as old as tourism itself – and it always reflects the destination and service benefits relevant to the current travelers’ needs, wants, and expectations. In other words, tourism campaigns must constantly move forward, and […]

Egg Protein Powder Global Market 2024: Driving Factors, Industry Challenges, Business Segmentation, Leading Countries, and Forecast Until 2033

Press release from: the business research company.

Egg Protein Powder Global Market

Permanent link to this press release:

You can edit or delete your press release Egg Protein Powder Global Market 2024: Driving Factors, Industry Challenges, Business Segmentation, Leading Countries, and Forecast Until 2033 here

Delete press release Edit press release

More Releases from The Business research company

All 5 Releases

More Releases for Egg

- Categories Advertising, Media Consulting, Marketing Research Arts & Culture Associations & Organizations Business, Economy, Finances, Banking & Insurance Energy & Environment Fashion, Lifestyle, Trends Health & Medicine Industry, Real Estate & Construction IT, New Media & Software Leisure, Entertainment, Miscellaneous Logistics & Transport Media & Telecommunications Politics, Law & Society Science & Education Sports Tourism, Cars, Traffic RSS-Newsfeeds

- Order Credits

- About Us About / FAQ Newsletter Terms & Conditions Privacy Policy Imprint

Benefit segmentation in the tourist accommodation market based on eWOM attribute ratings

- Original Research

- Open access

- Published: 19 April 2021

- Volume 23 , pages 265–290, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Karolina Nessel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8528-7391 1 ,

- Szczepan Kościółek ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7705-4216 1 ,

- Ewa Wszendybył-Skulska ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1308-6803 1 &

- Sebastian Kopera ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4802-3231 1

6418 Accesses

8 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Given the increasing importance of electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in the global tourism market, the purpose of the study was to estimate weights customers assign to main attributes of tourist accommodations embodied in easily observed eWOM numerical ratings and subsequently to determine segments of customers with homogenous preferences. To this goal, the preferences tourists attach to price and seven other accommodation attributes rated by Internet users on Booking.com were revealed with the analytical hierarchy process (AHP). Next, a two-stage clustering procedure based on these preferences was undertaken followed by profiling of the clusters in terms of their socio-demographics and travel characteristics. The results show that even if the ranking of the attributes is roughly the same for all the segments (with cleanliness, value for money, and location always in top four), all eight attributes effectively segment tourists into three clusters: “quality-seekers” (45% of the market), “bargain-seekers” (35%), and “cleanliness-seekers” (20%). The segments differ in terms of tourists’ income and expenditures, type of accommodation, actual payer for accommodation, and trip purpose. In contrast, socio-demographics, and most tourists stay variables are alike across the segments. The proposed method of benefit segmentation provides a new perspective for an exploitation of eWOM data by accommodation providers in their marketing strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

A Tourist Segmentation Based on Motivation, Satisfaction and Prior Knowledge with a Socio-Economic Profiling: A Clustering Approach with Mixed Information

From ota interface design to hotels’ revenues: the impact of sorting and filtering functionalities on consumer choices.

Developing Regional Strategies Based on Tourist Behaviour Analysis: A Multiple Criteria Approach

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Heterogeneity of tourists calls for a segmentation of the market in order to achieve a better targeting, positioning, marketing, or revenue management (Dolnicar 2007 ; Ahani et al. 2019 ). In the case of tourist accommodation, the consumer segmentation is usually based on socio-demographic variables, psychographics, and travel-related criteria. However, the limits of this approach to segmentation (Crawford-Welch 1990 ) have led researches to shift focus on to product and service benefits sought by customers. Consequently, for some scholars (Bowen 1998 ; Kim et al. 2020 ), the benefit segmentation (grouping consumers desiring the same sets of benefits) offers the best understanding of consumer behaviour in different market segments.

In the contemporary hospitality market, consumers increasingly rely on online environment to evaluate the benefits of different accommodation options. In particular, electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) has become one of the most important information sources for customers (Litvin et al. 2008 ; Filieri and McLeay 2013 ), and online textual reviews and ratings have been found to significantly influence tourists’ choices of accommodation (Ye et al. 2009 ; Cantallops and Salvi 2014 ; Park et al. 2019 ; Hu and Yang 2020 ). Even if some researchers find that consumer textual reviews have a greater impact on consumer purchase behaviour than numerical ratings (Noone and McGuire 2013 ), others claim that, given the amount of online data, easy access and processing of the eWOM are critical and make consumer-generated numerical ratings more influential on product purchase decisions than more detailed information (Sparks and Browning 2011 ; Yang et al. 2018 ). Both numerical ratings and textual reviews are usually presented by most online travel agents (OTAs) or travel rating portals, such as Booking.com, Expedia.com, TripAdvisor.com, enabling accommodation providers to increase efficiency of their marketing strategies (Yacouel and Fleischer 2012 ; Yang et al. 2018 ; Xia et al. 2019 ). Nevertheless, to fully use these data for an effective pricing and competitive positioning strategies, revenue and marketing managers need to understand how consumers integrate price and multiple sources of non-prices information available on OTAs’ websites in their multi-stage choice and booking process (Noone and McGuire 2013 ; Peng et al. 2018 ; Park et al. 2019 ; Hu and Yang 2020 ; Wang et al. 2020 ). The need gets even more urgent, as for many, especially medium and small accommodation providers, OTAs become the main distribution channel (Stangl et al. 2016 ). However, the smaller accommodation providers usually lack strong analytical capacities (Hyvärinen and Saltikoff 2010 ), and are not able to use advanced techniques developed on rich textual eWOM data. These organizations would profit from simpler models based on numerical eWOM indices.

The extant research on the role of both online textual reviews and numerical ratings in tourists’ behaviour and its use in marketing strategies of accommodation providers is extensive (for a detailed literature review see, e.g., Rhee and Yang 2015a ; Ahani et al. 2019 ). It has not, however, explored the use of numerical ratings on OTAs’ websites as a base for the benefit segmentation, i.e., to group guests into homogenous clusters having the same preferences towards a set of accommodation attributes rated by OTA users. On the other hand, the research has shown that these preferences are heterogeneous among tourists grouped according to some a priori criteria: context of trip, residence of tourists, or type of traveller (Rhee and Yang 2015a ; Wang et al. 2020 ).

Given the importance of numerical attribute ratings for guests’ choice and booking behaviour and their potential use in marketing strategies built on benefit segmentation for accommodation providers (especially the smaller ones), as well as the research gap in this area, the objective of this study is threefold: (1) to estimate the relative salience of the desired benefits embodied in numerical OTA ratings of accommodation attributes for the customers; (2) to determine homogeneous customer segments based on the importance of these attributes; (3) to evaluate the size and other characteristics of the segments.

To this goal, the research undertakes a cluster analysis of guests according to the importance they attach to price and seven other attributes of a tourist accommodation rated by Internet users on Booking.com—i.e., cleanliness, comfort, facilities, staff, value for money, free WiFi, location. Among ratings of accommodations made available by different online travel agents, those used by Booking.com are chosen because of Booking.com’s clear dominance among travel websites worldwide (Ebizmba 2018 ) and online accommodation distribution channels in Cracow, the area of our research (Kościółek et al. 2018 ). Consequently, the findings of the study should be of practical interest mainly to the mangers of accommodations heavily dependent on Booking.com as their source of customers. From the theoretical perspective, the main contribution of this study is the adoption of attribute categories used by the dominating online travel agent as a cognitive structure for the benefit segmentation.

2 Literature review

2.1 benefit segmentation.

When the goal is to serve a heterogeneous market, dividing it into mutually exclusive and homogeneous groups has proven to be a useful and thus widely used idea among marketing managers. A condition for an effective market segmentation is the appropriate choice of breakdown variables. In an a priori segmentation, criteria are defined before the procedure (as they are well-known or come from a well-defined classification scheme). On the other hand, the segmentation post hoc is based on market research survey and is derived on variables that turn out the most efficient in determination of homogeneous groups (Green et al. 1977 ; Mazanec 2000 ). Usually, once the segmentation based on chosen variables is done, the defined groups are additionally profiled, i.e. described in terms of other variables of interests. This enables a better understanding of consumers’ behaviour, but is also useful in segmentation validation (Brusco et al. 2017 ).

The procedure of segmentation is usually based on socio- and geo-demographics, psychographics, or behavioural variables (see e.g. Rondan-Cataluña and Rosa-Diaz 2014 for a literature review in the tourist accommodation market). However, according to Haley ( 1968 ), the way to effectively segment a market is to classify customers based on benefits they seek in a given product. The advantage of this approach for marketing and communication strategy formulation is grouping together customers with homogenous real needs, which are decisive in the purchase of the product (Loker and Perdue 1992 ; Kotler and Turner 1993 ; Frochot and Morrison 2001 ).

Unsurprisingly, benefit segmentation has been widely applied in the field of tourism, mainly to determine tourist segments according to their expected benefits of destinations, attractions, events, or activities (Paker and Vural 2016 ). Benefit studies in the accommodation market are relatively more limited (Guttentag et al. 2018 ). Usually, they are based on motives derived from interviews with customers and experts (Kim et al. 2020 ) or factor analysis of customers’ surveys regarding multiple hotel selection criteria or satisfaction attributes and limited to a special subgroup of tourists: business travellers in luxury hotels (Chung et al. 2004 ), female travellers (Khoo-Lattimore and Prayag 2015 ), or Airbnb users (Guttentag et al. 2018 ). Also the study by Ahani et al. ( 2019 ) limits the investigation to the guests of spa hotels. However, the latter study is the only one using the attributes derived from the textual reviews authored by Internet users (on TripAdvisor’s website) as the base for customers segmentation. The lack of a broader exploration of eWOM (other types of travellers and accommodations, other forms of eWOM) as the base for benefit segmentation in the accommodation market is puzzling considering the immense role of eWOM in this market.

2.2 Electronic word-of-mouth

Word-of-mouth is a complex process of information exchange between peers representing significant influencing power and, thus, shaping individual buying decisions and behaviours (Dichter 1966 ; Pan et al. 2007 ). The real revolution in WOM accompanied proliferation of the Internet, which offered individuals a new communication space, giving birth to eWOM (electronic Word-of-Mouth), defined as “all informal communications directed at consumers through Internet-based technology related to the usage or characteristics of particular goods and services, or their sellers” (Litvin et al. 2008 ). eWOM has been growing in importance since the early years of the twenty-first century (Bronner and De Hoog 2011 ), accompanied and fuelled by the rise of social media, which “flattened” the Internet and gave users new tools to create and publish their own content (O’Connor 2010 ; Filieri and McLeay 2013 ; King et al. 2014 ).

In the context of the customer decision-making process in tourism, eWOM is ranked the most important information source (Litvin et al. 2008 ; Filieri and McLeay 2013 ), and is probably the most important at the pre-trip stage, when tourists choose destination and most of the services they plan to buy during their trip. Extensive evidence search at this stage can be related to high risk involved in purchasing holiday product (Sirakaya and Woodside 2005 ). Information extracted from other travellers informs accommodation decisions (O’Connor 2010 ; Bronner and De Hoog 2011 ; Filieri and McLeay 2013 ), determines trust to particular suppliers and their offer (Sparks and Browning 2011 ; Dong et al. 2019 ), and shapes customer choices (Cantallops and Salvi 2014 ; Park et al. 2019 ; Hu and Yang 2020 ).

In the tourism industry, eWOM takes various forms supported by multitude of tools enabling creating content by users (Cheung and Thadani 2012 ), of which the most common are textual reviews and numerical ratings. The later provide a “shortcut” in a complex decision-making process (Sparks and Browning 2011 ) and reduce issues with interpreting a valence of text reviews (King et al. 2014 ; Yang et al. 2018 ). Moreover, the multi-dimensional numerical ratings of product attributes enable customers to verify the benefits that are the most relevant for them and provide consumers with a relatively fast and easy possibility to make a decision according to the ability of accommodation suppliers to perform on attributes of individual interest.

Notwithstanding these general observations, the latest research in hospitality eWOM has shown that the role of different online information elements (eWOM included) changes with the stage of booking process (Hu and Yang 2020 ) and consumers’ distinctive online decision-making patterns (Park et al. 2019 ). The heterogeneity is also observable in the sets of accommodation attributes that the OTA users are the most sensible to. Actually, Rhee and Yang ( 2015a ) have shown that these preferences are heterogeneous among TripAdvisor hotel guest grouped according to the context of their trip and their residence. In the same vein, Wang et al. ( 2020 ) have proved differences among different types of travellers in their approach to accommodation attributes derived simultaneously from TripAdvisor textual reviews and numeral ratings. Ahani et al. ( 2019 ), on the other hand, have found three homogenous clusters of spa hotel guests based on the relative salience of the attributes mentioned in the TripAdvisor textual reviews. This is unsurprising given a well-documented heterogeneity in relative importance of determinants of tourist accommodation selection or satisfaction.

2.3 Determinants of tourist accommodation selection

The research into the determinants of accommodation choice factors started with the seminal works by Lewis ( 1984 , 1985 ), who tested 66 hotel attributes of which location and price turned out to be the most decisive ones. Since then, the number and details of the selection attributes identified by researchers have grown immensely (Chu and Choi 2000 ; Dolnicar and Otter 2003 ; Shah and Trupp 2020 ). Besides location and price, literature has shown, inter alia, the importance of room quality, service quality, cleanliness, safety and security, hotel reputation, or atmosphere (Kim et al. 2020 ). Moreover, these determinants have been proved to be heavily influenced by traveller type and trip purpose (Wang et al. 2020 ), gender (Hao and Har 2014 ; Kim et al. 2018 ), destination nature and origin of tourists (Ying et al. 2020 ). They have also been shown to be interlinked and dependent on the stage of accommodation selection (Hu and Yang 2020 ).

In this research, we follow Booking.com, which—as main numerical indices for each accommodation—presents its price and ratings of seven attributes: location, cleanliness, comfort, facilities, staff, value for money, and free WiFi quality.

Price of an accommodation is habitually the basic decision criterion (Song et al. 2011 ), especially for leisure tourists (Lewis 1985 ; Chow et al. 1995 ; Parasuraman et al. 1998 ) For the business tourists price doesn’t seem less important than for the leisure ones (Lewis 1985 ; Kim et al. 2020 ), but it is found to be of lesser significance than location, quality, and comfort (Wong and Chi-Yung 2002 ; Kim and Park 2017 ). Moreover, price is more important for those travelling less frequently and for shorter periods, as well as for those travelling with their families or friends (Wong and Chi-Yung 2002 ), deciding to stay at a lower standard hotel (Rhee and Yang 2015b ), or for women than men (McCleary et al. 1994 ). On the other hand, the price discounts and promotions do not necessarily increase sales, as tourist may associate them negatively with a perceived hotel quality (Hu and Yang 2020 ).

Location encompasses accessibility of points of interests, transport convenience, and surrounding environment (Masiero et al. 2019 ). In particular, the location may be crucial for tourists who expect easy access to the places they want to visit and the events in which they intend to participate (Tsaur and Tzeng 1996 ). Similarly, business travellers prefer being located near a business meeting spot (McCleary et al. 1993 ). Although location has usually been perceived as the most important attribute of an accommodation (Barros 2005 ; Chou et al. 2008 ), there is a significant heterogeneity in tourists’ hotel location preferences (Masiero et al. 2019 ). For instance, the location is of more importance than price, or value for money for women travelling on business (Hao and Har 2014 ), as well as for more affluent tourists (Zaman et al., 2016 ).

Cleanliness is one of the most important factors determining the choice of a particular hotel, and one of the main sources of eventual dissatisfaction with the stay (Lewis 1987 ; Mehta and Vera 1990 ; Saleh and Ryan 1992 ; Lin and Su 2003 ; Huang et al. 2015 ). Moreover, the concept of cleanliness has been shown to concern not only rooms, but also other hotel areas: bathrooms, toilets, hotel entrance, parking, lobbies, and restaurants. Cleanliness is also associated with safety (Kozak et al. 2007 ; Amblee 2015 ) and decreased health risks (Shin and Kang 2020 ). Some researchers have found that cleanliness is an attribute to which women pay more attention than men, both when choosing a hotel, and while staying at it (Zemke et al. 2015 ). It is also more important for business travellers than for leisure tourists (McCleary et al. 1993 ). On the other hand, Knutson ( 1988 ) has showed that cleanliness of the room is the most important attribute in choosing a hotel by tourists in the US, regardless of the type of tourists and accommodation.

Comfort at a hotel is usually seen through the prism of sleep quality, i.e. such factors as comfortable bed, quiet and soundproof rooms, appropriate temperature, lighting, room odour, and noise level (Liu et al. 2013 ; Rhee and Yang 2015b ). Zaman et al. ( 2016 ) showed that comfort is less important when choosing a hotel than location or value for money. Nevertheless, its importance varies with type of the guest. According to Lockyer ( 2002 ), comfort is the most important attribute for business travellers and those travelling alone. By contrast, for those travelling with friends, comfort is the least important, whereas people travelling with families and as a couple value comfort lower than price, but higher than location and cleanliness.

Hotel facilities are usually associated with additional services (i.e. wet bar in the room, coffee machine or kettle in the room, safe box, luggage room, storage room for recreational equipment, free parking, etc.). Depending on the establishment and its standard, facilities are included in the price of stay, or paid additionally. Hotels, in order to be more competitive, try to offer their guests more and more facilities (Dolnicar and Otter 2003 ). However, the majority of studies prove that amenities are perceived as an attribute of lesser importance than price and location (Chu and Choi 2000 ), or value for money and staff (Qu et al. 2000 ). By contrast, for Chinese outbound travellers in Macau, room facilities proved to be the most important hotel choice factors (McCartney and Ge 2016 ). Facilities, although usually not the primary attribute of hotel choice, are more important for business tourists than for leisure ones (Chu and Choi 2000 ; Shanka and Taylor 2013 ).

Quality of personal interactions with staff is often a key element in the satisfaction with the quality of hotel services (Parasuraman et al. 1998 ; Kim et al. 2016 ), both for business and leisure travellers (Barsky and Labagh 1992 ), and particularly in higher end hotels (Chu and Choi 2000 ). However, other studies have found it of lesser importance than several other attributes (Rhee and Yang 2015a ; Wang et al. 2020 ). Moreover, as an accommodation selection criterion the importance of this attribute is usually found to be relatively lower (Sohrabi et al. 2012 ; Wang et al. 2020 ).

Value for money is determined as a trade-off between perceived costs (mainly monetary ones) and benefits (Zeithaml 1988 ). While evaluating accommodation attributes customers search for the one presenting the highest value for the lowest possible price (Gupta and Kim 2010 ), regardless of the accommodation type (Hu and Hiemstra 1996 ). Value for money has been shown to be the most important factor of hotel choice by Parasuraman et al. ( 1998 ) and McCartney and Ge ( 2016 ), while Zaman et al. ( 2016 ) showed that value for money, following price, is the second important criterion.

Free and reliable WiFi at a hotel seems an indispensable component of the present-day hospitality offer. So far, however, research has pointed to the relatively small significance of this attribute for the hotel guests in their choice decisions (Lockyer 2005 ; Shanka and Taylor 2013 ), valuing it less than comfort and safety (Sohrabi et al. 2012 ). On the other hand, a weak WiFi is a frequent reason for a negative eWOM (Xu 2018 ).

Taken together, the studies reviewed thus far indicate that despite the extensive research on the heterogeneity of relative importance of different accommodation attributes for the tourist behaviour, the segmentation based on this heterogeneity is quite limited. Moreover, the benefit segmentation according to importance the customers attach to the attributes found in eWOM is restricted to the only study concerning spa hotel guests and based on textual reviews (Ahani et al. 2019 ). Therefore, the following section presents the results of the study undertaking the benefit segmentation in the accommodation market based on the set of attributes that are rated by Booking.com users.

The study was conducted within the framework of bounded rationality theory (Simon 1979 ) and multi-attribute utility theory (Keeney et al. 1993 ). The theories together stipulate that people act as rational as possible in the limits of their imperfect capacities of data analysis and base their decisions on a set of the most decisive criteria (with the use of heuristics and unequal weight accorded to readily accessible information).

3 Materials and methods

3.1 survey instrument.

The survey questionnaire consisted of two main sections fitted into two pages. The first included 28 pairwise comparisons of relative importance of seven crucial accommodation attributes adopted directly from the Booking.com review form (cleanliness, location, comfort, facilities, staff, value for money, and free WiFi), and an additional variable: price. In the second stage, 18 profiling questions were asked. All of them were derived from a review of the literature on benefit segmentation in tourism studies, and included socio-demographics (age, gender, country of residence, education level, occupation, monthly income), tourist stay characteristics (first time vs repeat visit to the destination, trip purpose, travel party composition, accommodation type and reservation channel, payer for the accommodation), and tourism consumption features (travel expenditure on accommodation, food and beverages, activities).

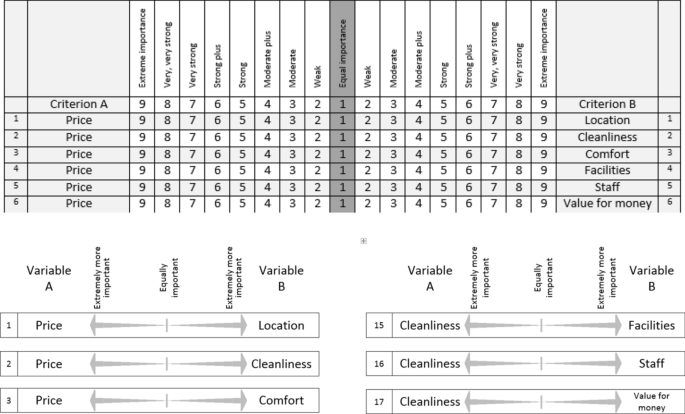

Initially, two versions of the survey were developed with different formulations of pairwise comparisons (numerical versus graphical scales)—Fig. 1 in Appendix. The pilot study carried out on 40 persons indicated that the graphical scale led to more consistent answers, and this version was adopted in the data collection process. The graphical answers were converted into numbers in the coding stage of the data preparation (rounding to the nearest integral value to match the numerical scale usually used in AHP). The final versions of the paper questionnaire were prepared in Polish and English.

Formulation of pairwise comparisons in the alternative pilot versions of the survey instrument

3.2 Data collection

The target population of the study was tourists visiting Cracow, which is a UNESCO World Heritage site and a major tourist destination in Poland (over 14 million arrivals in 2019) famous for its cultural, historical, and architectural attractions. All tourists, regardless of their reservation channel in this particular trip, were targeted as they are all potential Booking.com customers.

The data were collected in the most popular tourist attractions of the city agglomeration between April and June 2018. As many tourists as possible were asked to complete the questionnaire. Each first available tourist met by an interviewer was asked to participate in the survey and approximately 20% of them agreed. Participants were first briefed by the interviewer about the purpose of the study and the way to indicate the relative importance in each pair of attributes. These explanations, accompanied by two examples, were also printed at the beginning of the survey sheet.

As the most reliable data concerning tourist market in Cracow, based on accommodation suppliers’ reports, indicate an average annual proportion of domestic to international tourists being 51:49 in 2016 (Statistical Office in Kraków 2017 ), a quota sampling was applied aiming to achieve a parity between both groups of visitors. The surveys were conducted in five waves—when the balance between domestic and international tourists was disturbed, interviewers targeted the under-represented group in the following wave. In total, 964 fully completed questionnaires were collected.

3.3 Data analysis

The data analysis in the study comprised three main stages. First, determination of relative weights customers attach to each criterion was performed using a part of an analytic hierarchy process. In AHP, which was introduced and developed by Saaty ( 1980 ), the relative weights result from the solution of Eigen value problem of the matrix made of all pairwise comparisons. In this research AHP Excel template developed by Goepel ( 2013 ) was used to solve the problem mathematically, and to determine the weighting and the consistence ratio of individual respondents.

The advantage of AHP in this study consists not only in its suitability in multi-criteria decision-making problems, but also in its ability to handle situations of subjective judgements (Saaty 1980 ). On the other hand, its inconvenience lies in a certain difficulty for respondents in logical and consistent evaluation of all pairs of attributes. This difficulty rises with the number of attributes. The consistency ratio in AHP usually should not exceed 0.10, but the threshold may be enlarged to 0.20 in more difficult situations (Saaty 2002 ). In our study, a consistency ratio not greater than 0.2 was observed in 540 surveys, i.e. 56% of the initial sample. Only these surveys made our final sample and were subsequently clustered and profiled.

In the second step of the data analysis, two-stage clustering procedure based on individual criteria weightings was applied in order to identify customer segments with similar preferences in terms of accommodation attribute weights. Firstly, Ward’s hierarchical cluster analysis with the Euclidean distance was undertaken in order to determine the number of clusters. Secondly, a non-hierarchical K-means method was applied to define the final segments. According to the literature, a two-stage clustering procedure increases validity of solutions (Hair et al. 1998 ).

In the final stage of the data analysis, a profiling of the clusters in terms of their socio-demographics, and travel characteristics was carried out.

4.1 Sample profile

The sample (Table 2 ) is roughly equally shared among males (49%) and females (51%), as well among international (52%) vs. domestic (48%) tourists. More than ¾ of the sample are comprised of people under 45 years old, employed or self-employed, with at least high school education. The majority of them (63%) earn less than 1500€ per month. They are rather repeat visitors to Cracow (56%), coming mainly for leisure (42%), and mostly as individual tourists (88%). They travel in an adult group (31%) or in a couple (25%), usually without children (90%). Most of them stay fewer than five days in the city (82%), usually in 3-star hotels (28%) and private apartments (20%), which they have booked personally via Booking.com (28%), or someone else has booked for them (22%). In any case, most (74%) have paid for the accommodation themselves. The threshold of 40€ for daily expenses for accommodation concerns 63% of tourists, for food and beverages—62% of them, and for tourist activities—almost all of them (88%).

4.2 Pairwise comparisons of attributes

The relative importance of accommodation attributes was determined by pairwise comparisons. For the total sample, the most important criterion is cleanliness (0.189), closely followed by value for money (0.171), location (0.149), and price (0.142). The weight of comfort itself is at average level (0.113), while facilities (0.084), free WiFi (0.081) and staff (0.072) are valued the least—Table 1 .

A visual inspection of data and the results of Lilliefors tests indicate that criteria variables are not normally distributed. Therefore, in subsequent analysis involving these variables, non-parametrical tests are used. Regarding the correlation between the criteria, no multicollinearity is observed, and, thus, a clustering procedure based on these variables is possible.

4.3 Cluster analysis

The segmentation analysis based on eight accommodation criteria allows to determine three clusters of tourists (Table 1 ). The biggest segment in the market (45%), Cluster 1 (labelled “quality-seekers”) groups tourists relatively more sensitive to such criteria as comfort, facilities, free WiFi, and staff. These variables make 47% of weight for the tourists of this cluster, at the relative expense of a lower than average importance attached to price (10%).

The second in terms of size (35%) is Cluster 2 (“bargain-seekers”), in which price is the most important criterion (23%). Interestingly, compared to quality-seekers, these tourists also relatively more value accommodation location. At the same time, they put lower weight on comfort, facilities, free WiFi, and staff, but they attach the same importance to cleanliness, and value for money.

The smallest, Cluster 3 (20%, “cleanliness-seekers”), comprises tourists giving an extra importance to cleanliness (31%), at the relative expense of value for money.

To determine the influence of each variable on creation of the clusters, a series of Kruskal–Wallis tests was performed. Results (Table 1 ) indicate that, although all variables have statistically significant impact (p < 0.01), the strength of the impact is not similar. In fact, the clusters differ mostly in terms of importance attached to price and cleanliness, while the differences are the smallest in case of the weights of value for money and location. In regard to within-cluster variability, the standard deviations (Table 1 ) indicate that the clusters are most homogenous in terms of cleanliness, and the least in terms of free WiFi.

4.4 Profile analysis

In order to profile the segments, cross tabulations with socio-economic and demographic variables, tourist stay characteristics, and consumption variables were undertaken (Table 2 ). The chi-square tests indicate that clusters are similar in terms of socio-demographics (gender, age, education, country of residence, occupation), and most tourist stay variables (first vs. repeat visit, travel party composition, presence of children, length of stay, accommodation reservation channel). The differences lie mainly in economic dimensions: tourists’ income and expenditures, as well as type of accommodation, actual payer for the accommodation, and, additionally, trip purpose.

With regard to income variable, among people earning less than 1500€ per month, there is a clear overrepresentation of bargain-seekers tourists, and a smaller underrepresentation of quality-seekers (in 1000–1499€ group). The situation is symmetrical among higher income tourists: a clear underrepresentation of bargain-seekers, and an overrepresentation of quality-seekers (especially in 1500–1999€ group). On the other hand, the distribution of cleanliness-oriented tourists follows the average distribution in the market.

The pattern of heterogeneity is roughly the same in case of spending on accommodation: the spenders of less than 20€ per night are relatively more present in the price sensitive cluster, and less among quality and cleanliness-seekers, while prices of more than 40€ are paid relatively less often by price sensitive customers. The situation is similar in regard to spending on tourist accommodation: small spenders (1–19€) are overrepresented in Cluster 2, and underrepresented in Cluster 1. Additionally, the latter cluster has an overrepresentation of tourists spending 40–59€. There is no specificity in terms of activity spending for Cluster 3. Finally, although the association of the clusters and spending on food and beverages is statistically significant only at p < 0.10, logical relations can be observed in this regard: higher spenders are found relatively more often among comfort-oriented tourists, while smaller spenders are prevailing among price (and to a lesser degree also cleanliness)-sensitive guests. According to Cramer’s tests, the associations between clusters on the one hand, and income and spending variables on the other, are strong (with the exception of spending on food and beverages).

An even stronger association is observed between cluster and accommodation type. In fact, hostel shared rooms are relatively more often chosen by price conscious tourists, 1 or 2-star hotel guests are underrepresented in the cleanliness-seeking cluster, while 3-star hotel customers are overrepresented in the quality-seeking cluster. Unsurprisingly, 4 and 5-star hotels are relatively less often chosen by price-oriented tourists, and relatively more often by cleanliness sensitive ones. Finally, private apartments are clearly relatively less chosen by tourists focused on comfort, but relatively more often by guests looking for cleanliness.

The most important differences between clusters can be seen in terms of trip purpose (an exceptionally high association, V ACCOMODATION = 0.43). In fact, among tourists coming to Cracow for religious purposes, there were relatively fewer comfort-oriented, but more price-oriented people. On the other hand, people coming to see relatives and friends were underrepresented in the cleanliness-oriented cluster, but overrepresented in the price sensitive cluster. Moreover, price-oriented people were underrepresented among tourists coming for business and leisure. Finally, in the event category, there were relatively fewer cleanliness-sensitive persons.

The final variable differentiating the clusters is the actual payer for the accommodation (the strength of this association is moderately strong). The most striking, and expected, relative difference is observed when the accommodation is paid by the tourist’s company—in this case, there is a clear underrepresentation of bargain-seeking guests.

Overall, the data analysis leads to the determination of three distinctive clusters:

Cluster 1—quality-seekers (45% of the sample). The tourists in this cluster stand out because of the higher weights they put on accommodation quality embodied by comfort, facilities, free WiFi, and staff. And they are ready to pay a higher price for it. They look for the accommodation quality choosing (relatively more often than the rest of the market) 3-star hotels, and avoiding private apartments. They also spend more than others on tourist attractions, and food and beverages. Their higher spending is matched by their higher income. They are relatively underrepresented among religious tourists in Cracow.

Cluster 2—bargain-seekers (35% of the sample). The most striking feature of this cluster is the high importance attached to the price criterion. Moreover, the tourists in this cluster value localization slightly more, and comfort slightly less than the others. Consequently, their spending on accommodation, and also on other tourist attractions, as well as food and beverages, is lower, as they tend to stay with friends, family, or in hostel shared rooms relatively more often. Therefore, they are underrepresented among 4 and 5-star hotel guests. Their consumption pattern is correlated with their lower than average personal income. The purpose of their visit to Cracow was less business and leisure-oriented, as they came more to see friends and relatives, and for religious reasons.

Cluster 3—cleanliness-seekers (20% of the sample). The tourists in this cluster are extremely sensitive to cleanliness criterion and are ready to give up on value for money. Effectively, compared to other clusters, they are relatively unlikely to pay less than 40€ per night or choose a free accommodation. In fact, they are overrepresented in 4 and 5-star hotels, and among private apartment customers (and underrepresented in budget accommodations). Their trip purpose to Cracow was relatively rarely an event or visiting family and friends.

Notwithstanding the above differences among the clusters, some similarities across all three groups have to be underscored: (1) cleanliness, value for money, and location are among top priorities among tourists in all segments, making ca. 50% of total criteria weights; (2) all segments are most similar in terms of high importance attached to value for money, and location criteria; (3) clusters are alike in terms of socio-demographics, and most tourist stay variables.

5 Discussion and conclusion

5.1 discussion.

Driven by the importance of eWOM attribute ratings for guests’ choice and booking behaviour and its potential use in marketing strategies for accommodation providers, this study determined the relative importance tourists attach to the set of accommodation attributes embodied in numerical ratings on the website of the dominant online travel agent, Booking.com, and defined segments of tourists sharing the same combinations of desired attributes.

In the limited literature on benefit segmentation in the accommodation sector, various approaches to enumerating benefits have been applied for consumer segmentation—interviews with customers and experts (Kim et al. 2020 ), factor analysis of customers’ surveys based on literature review (Chung et al. 2004 ; Guttentag et al. 2018 ), or data mining of textual eWOM (Ahani et al. 2019 ). In this study, in contrast, a predetermined set of attribute ratings present on the online travel agent’s website has been adopted as potential clients are assumed to base their decisions on a limited set of the most readily accessible information (Simon 1979 ; Keeney et al. 1993 ).

Naturally, the more granular benefit classification is, the more precise results in terms of customers’ needs may be (potentially) obtained. For example, Chung et al. ( 2004 ) enlisted 16 benefit factors to segment customers. However, the rise of the number of benefits enlisted decreases the tool’s practicality for day-to-day managerial application. This study shows that the seven benefits listed on Booking.com together with price, all of which (except one: free WiFi) appeared in the previously cited work of Chung et al. ( 2004 ), are sufficient to identify basic customer segments with distinct travel consumption behaviours.

Actually, all eight attributes discriminate tourists, even if their ranking is roughly the same for the delimited clusters. Among the four top criteria for most of the visitors one finds cleanliness, value for money, and location, confirming findings by many scholars having used other sets of attributes (Parasuraman et al. 1998 ; Zaman et al. 2016 ; McCartney and Ge 2016 ; Ahani et al. 2017 ; Wang et al. 2020 ). Also the findings of Rhee and Yang ( 2015a ), has been partially confirmed, with the exception of localisation that turned out clearly less important in their study than sleep quality, room, and service. On the other hand, facilities, free WiFi, and staff are generally valued the least—as also observed by Chu and Choi ( 2000 ), Qu et al. ( 2000 ) and Shanka and Taylor ( 2013 ).

Notwithstanding general similarities in the attribute rankings, differences in weights accorded to each attribute justify grouping tourists in three clusters. The tourists referred to as "quality-seekers" (Cluster 1) are probably the most attractive for the accommodation industry, mainly for hotels. They are the most profitable customers for hotel establishments because of their ability to pay more for a stay, provided the comfort of the services offered is higher, and the scope of amenities is greater. The attributes valued relatively more in this cluster match those found among tourists spending more on accommodation in Paris or Macao (Zaman et al. 2016 ; McCartney and Ge 2016 ).

Cluster 2 represents “bargain-seekers”, i.e. tourists looking for accommodation facilities offering low prices, but, at the same time, conveniently located. According to Lewis ( 1985 ), price and location are the basis for the hotel selection mainly for leisure tourists. In our research sample, the frugal tourists come to Cracow mostly for leisure, but, at the same time, they were relatively overrepresented among tourists coming for an event, religious purpose, and to see friends and relatives. The latter relationship is consistent with observations by Wong and Chi-Yung ( 2002 ). The frugal tourists in Cracow show lower incomes, which, in turn, makes them choose accommodation of lower standards, confirming the findings by Chu and Choi ( 2000 ), who showed that, for such tourists, comfort and facilities are less important than location and price.

“Cleanliness-seekers" in Cluster 3 may be considered demanding, yet profitable clients. For them, the focal attribute is cleanliness, and they are ready to pay the price for it. They are wealthy tourists overrepresented among customers of 4 and 5-star hotels, and private luxury apartments. These characteristics confirm findings by Rhee and Yang ( 2015b ) who proved that hotel guests using high standard hotels consider cleanliness to be the most important attribute. Moreover, in our study, the cleanliness is high on most of the tourists’ priorities lists when choosing an accommodation, corroborating findings of many researchers studying either hotel choice criteria or sources of hotel dissatisfaction (Lockyer 2003 ; Zaman et al. 2016 ).

5.2 Implications and contributions