- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Henry Hudson

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

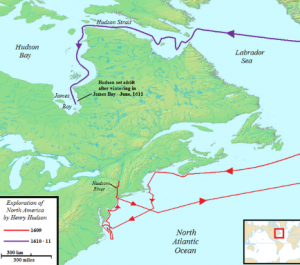

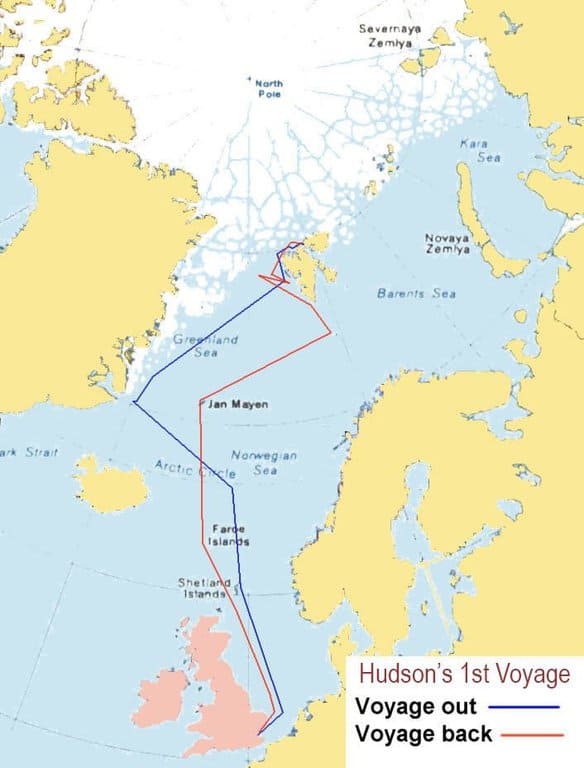

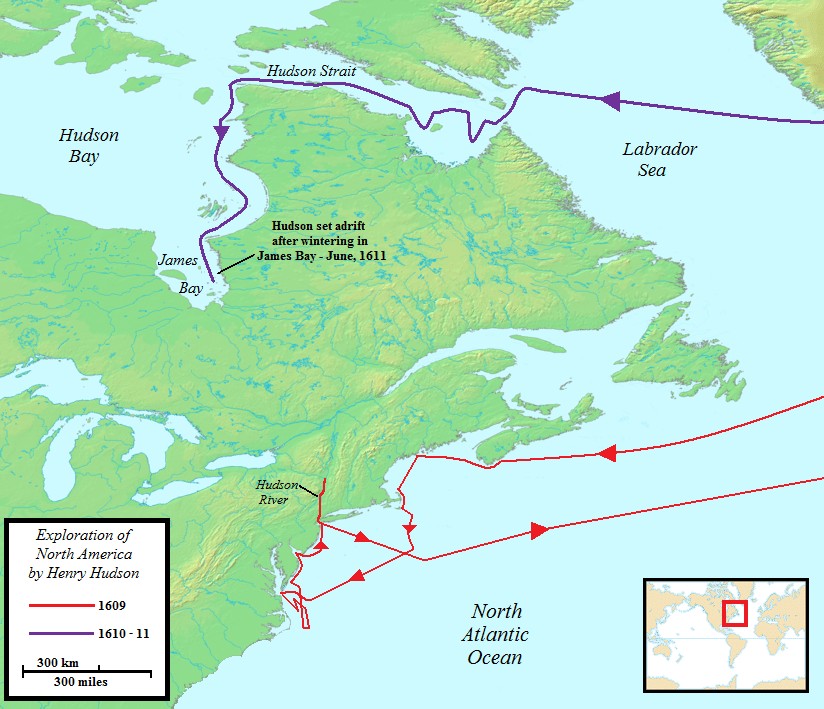

Henry Hudson made his first voyage west from England in 1607, when he was hired to find a shorter route to Asia from Europe through the Arctic Ocean. After twice being turned back by ice, Hudson embarked on a third voyage in 1609. This time, he chose a southern route, drawn by reports of a channel across the North American continent to the Pacific. After navigating the Atlantic coast, Hudson’s ships sailed up a great river (today’s Hudson River) but turned back when they determined it was not the channel they sought. On a fourth and final voyage in 1610-11, Hudson spent months in the vast Hudson Bay before he fell victim to a mutiny by his crew. Hudson’s discoveries laid the groundwork for Dutch colonization of the Hudson River Valley, as well as English land claims in Canada.

Birth and Early Life

Though little is known about Hudson’s early life, most historians agree that he was born around 1565 in England, and later lived in London . It’s known that he received a better education than many, because he could read, write, and do mathematics. He also studied navigation and earned widespread renown for his skills, as well as his knowledge of Arctic geography.

Hudson married a woman named Katherine, and together they had three sons: Oliver, John and Richard. John would later accompany his father on his expeditions.

In 1607, the Muscovy Company of London provided Hudson financial backing based on his claims that he could find an ice-free passage past the North Pole that would provide a shorter route to the rich markets and resources of Asia. Hudson sailed that spring with his son John and 10 companions. They traveled east along the edge of the polar ice pack until they reached the Svalbard archipelago, well north of the Arctic Circle, before hitting ice and being forced to turn back.

Did you know? Knowledge gained during Henry Hudson's four voyages significantly expanded on that from previous explorations made in the 16th century by Giovanni da Verrazano of Italy, John Davis of England and Willem Barents of Holland.

The following year, Hudson made a second Muscovy-funded voyage between Svalbard and the islands of Novaya Zemlya, to the east of the Barents Sea, but again found his way blocked by ice fields. Though English companies were reluctant to back him after two failed voyages, Hudson was able to gain a commission from the Dutch East India Company to lead a third expedition in 1609.

The Half Moon

While in Amsterdam gathering supplies, Hudson heard reports of two possible channels running across North America to the Pacific. One was located around latitude 62° N (based on English explorer Captain George Weymouth’s 1602 voyage); the second, around latitude 40° N, had been recently reported by Captain John Smith .

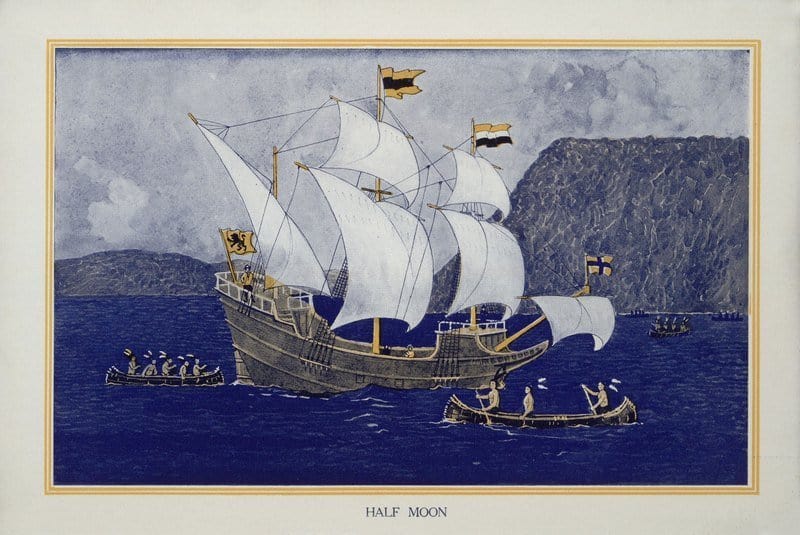

Hudson departed from Holland on the ship Halve Maen ( Half Moon ) in April 1609, but when adverse conditions again blocked his route northeast, he ignored his agreement with his employers to return directly and decided to sail to the New World in search of the so-called “northwest passage.”

After landing in Newfoundland, Canada, Hudson’s expedition traveled south along the Atlantic coast and put into the great river discovered by Florentine navigator Giovanni da Verrazano in 1524. They traveled up the river about 150 miles, to what is now Albany, before deciding that it would not lead all the way to the Pacific and turning back. From that time on, the river would be known as the Hudson River.

On the return voyage, Hudson docked at Dartmouth, England, where English authorities acted to prevent him and his other English crew members from making voyages on behalf of other nations. The ship’s log and records were sent to Holland, where news of Hudson’s discoveries spread quickly.

Hudson’s Final Voyage

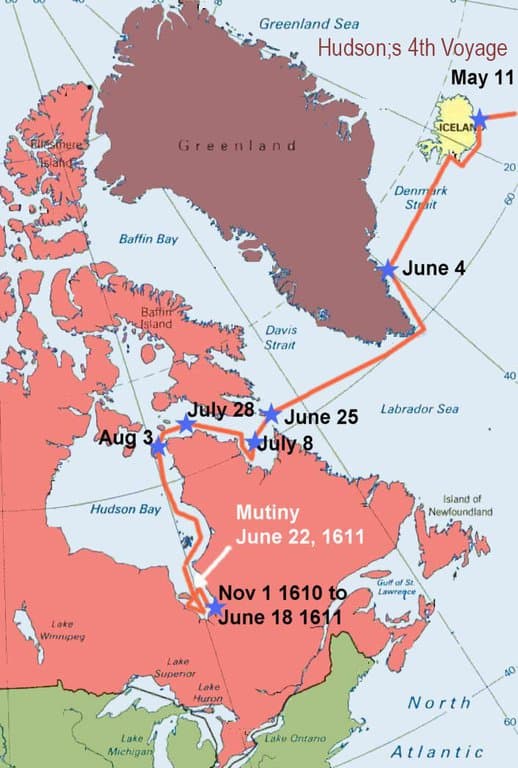

The British East India Company and the Muscovy Company, along with private sponsors, jointly funded Hudson’s fourth voyage, on which he sought the possible Pacific-bound channel identified by Weymouth. Hudson sailed from London in April 1610 in the 55-ton ship Discovery , stopped briefly in Iceland, then continued west.

After traversing the coast again, he passed through the inlet Weymouth had described as a potential entry point to a northwest passage. (Now called Hudson Strait, it runs between Baffin Island and northern Quebec.) When the coastline suddenly opened up towards the south, Hudson believed he might have found the Pacific, but he soon realized he had sailed into a gigantic bay, now known as Hudson Bay.

Hudson continued sailing southward along the bay’s eastern coast until he reached its southernmost extremity at James Bay, between northern Ontario and Quebec. While enduring harsh winter conditions with no outlet to the Pacific in sight, some crew members grew restless and hostile, suspecting Hudson of hoarding rations to give to his favorites.

Last Days of Henry Hudson

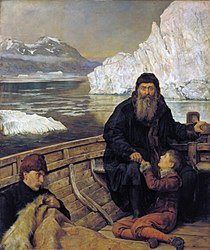

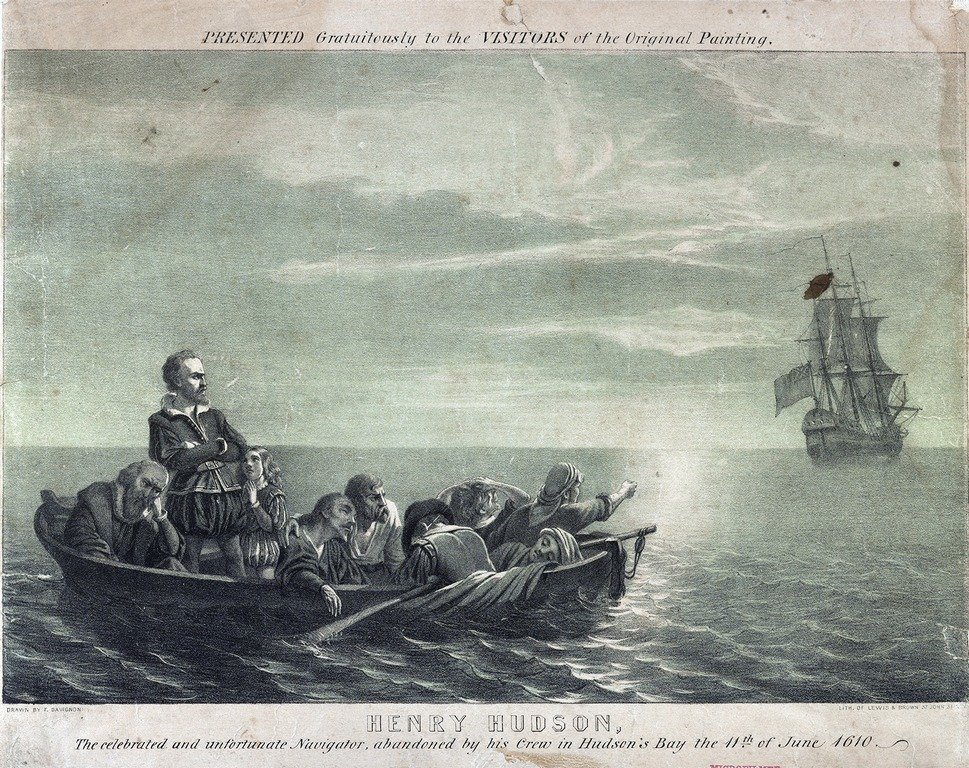

In June 1611, as the expedition began heading back to England, sailors Henry Green and Robert Juet (who had been demoted as mate) led a mutiny. Seizing Hudson and his son, they cast them adrift on Hudson Bay with a few supplies in a small open lifeboat, along with seven other men who were suffering from scurvy.

Hudson, his 17-year-old son John, and his men were never heard from again. After further troubles on their return trip to England, by the time Discovery encountered a fleet of fishermen off the coast of Ireland in September 1611, the original crew of 23 was down to just eight survivors. They were arrested for mutiny, but never punished.

Henry Hudson. The Mariner’s Museum and Park . Henry Hudson. The Canadian Encyclopedia . Henry Hudson. PBS . Strangers In A New Land. American Heritage .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Henry Hudson

English explorer Henry Hudson embarked on multiple sailing voyages that provided new information on North American water routes.

(1565-1611)

Who Was Henry Hudson?

Believed to have been born in the late 16th century, English explorer Henry Hudson made two unsuccessful sailing voyages in search of an ice-free passage to Asia. In 1609, he embarked on a third voyage funded by the Dutch East India Company that took him to the New World and the river that would be given his name. On his fourth voyage, Hudson came upon the body of water that would later be called the Hudson Bay.

Considered one of the world's most famous explorers, Henry Hudson, born in England circa 1565, never actually found what he was looking for. He spent his career searching for different routes to Asia, but he ended up opening the door to further exploration and settlement of North America.

While many places bear his name, Hudson remains an elusive figure. There is little information available about the famous explorer's life prior to his first journey as a ship's commander in 1607. It is believed that he learned about the seafaring life firsthand, perhaps from fishermen or sailors. He must have had a talent for navigation early on, enough to merit becoming a commander in his late 20s. Prior to 1607, Hudson probably worked aboard other ships before being appointed to lead one on his own. Reports also indicate that he was married to a woman named Katherine and they had three sons together.

First Three Voyages

Hudson made four journeys during his career, at a time when countries and companies competed with each other to find the best ways to reach important trade destinations, especially Asia and India. In 1607, the Muscovy Company, an English firm, entrusted Hudson to find a northern route to Asia. Hudson brought his son John with him on this trip, as well as Robert Juet. Juet went on several of Hudson's voyages and recorded these trips in his journals.

Despite a spring departure, Hudson found himself and his crew battling icy conditions. They had a chance to explore some of the islands near Greenland before turning back. But the trip was not a total loss, as Hudson reported numerous whales in the region, which opened up a new hunting territory.

The following year, Hudson once again set sail in search of the fabled Northeast Passage. The route he sought proved elusive, however. Hudson made it to Novaya Zemlya, an archipelago in the Arctic Ocean to the north of Russia. But he could not travel further, blocked by thick ice. Hudson returned to England without achieving his goal.

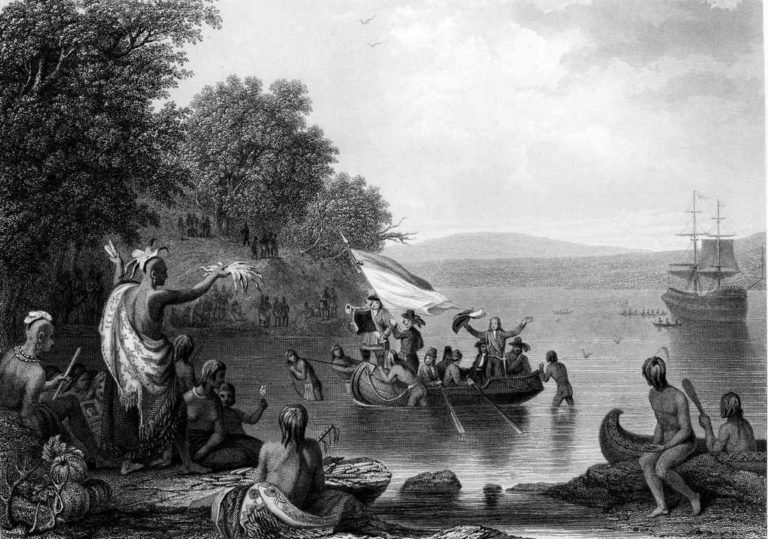

Crossing the Atlantic Ocean, Hudson and his crew reached land that July, coming ashore at what is now Nova Scotia. They encountered some of the local Indigenous peoples there and were able to make some trades with them. Traveling down the North American coast, Hudson went as far south as the Chesapeake Bay. He then turned around and decided to explore New York Harbor, an area first thought to have been discovered by Giovanni da Verrazzano in 1524. Around this time, Hudson and his crew clashed with some local Indigenous peoples. A crew member named John Colman died after being shot in the neck with an arrow, and two others on board were injured.

After burying Colman, Hudson and his crew traveled up the river that would later carry his name. He explored the Hudson River up as far as what later became Albany. Along the way, Hudson noticed that the lush lands that lined the river contained abundant wildlife. He and his crew also met with some of the Indigenous peoples living on the river's banks.

On the way back to the Netherlands, Hudson was stopped in the English port of Dartmouth. The English authorities seized the ship and the Englishmen among the crew. Upset that he had been exploring for another country, the English authorities forbade Hudson from working with the Dutch again. He was, however, undeterred from trying to find the Northwest Passage. This time, Hudson found English investors to fund his next journey, which would prove to be fatal.

Final Journey and Death

Aboard the ship Discovery , Hudson left England in April 1610. He and his crew, which again included his son John and Robert Juet, made their way across the Atlantic Ocean. After skirting the southern tip of Greenland, they entered what became known as the Hudson Strait. The exploration then reached another of his namesakes, the Hudson Bay. Traveling south, Hudson ventured into James Bay and discovered that he'd come to a dead end.

By this time, Hudson was at odds with many in his crew. They found themselves trapped in the ice and low on supplies. When they were forced to spend the winter there, tensions only grew worse. By June 1611, conditions had improved enough for the ship to set sail once again. Hudson, however, didn't make the trip back home. Shortly after their departure, several members of the crew, including Juet, took over the ship and decided to cast out Hudson, his son and a few other crew members. Mutineers put Hudson and the others in a small boat and set them adrift. It is believed that Hudson and the others died of exposure sometime later, in or near the Hudson Bay. Some of the mutineers were later put on trial, but they were acquitted.

More European explorers and settlers followed Hudson's lead, making their way to North America. The Dutch started a new colony, called New Amsterdam, at the mouth of the Hudson River in 1625. They also developed trade posts along the nearby coasts.

While he never found his way to Asia, Hudson is still widely remembered as a determined early explorer. His efforts helped drive European interest in North America. Today his name can be found all around us on waterways, schools, bridges and even towns.

QUICK FACTS

- Birth Year: 1565

- Birth City: England

- Birth Country: United Kingdom

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: English explorer Henry Hudson embarked on multiple sailing voyages that provided new information on North American water routes.

- Business and Industry

- Death Year: 1611

- Death date: June 22, 1611

- Death City: In or near the Hudson Bay

- Death Country: Canada

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

- The land is the finest for cultivation that I have ever in my life set foot upon, and it also abounds in trees of every description.

- You cannot fly like an eagle with the wings of a wren.

- I sailed to the shore on one of their canoes with an old man who was the chief of a tribe consisting of 40 men and 17 women.

- I used all diligence to arrive at London, and therefore I now gave my crew a certificate under my hand, of my free and willing return, without any persuasion by any one or more of them. For when we were at Nova Zembla, on the 6th of July, void of hope of a northeast passage ... I therefore resolved to use all means I could to the northeast.

- This land may be profitable to those that will adventure it.

Famous British People

Mick Jagger

Agatha Christie

Alexander McQueen

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Amy Winehouse

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

- Chance Kelly

- Aug 17, 2023

Henry Hudson’s Discoveries and How They Changed The World

Updated: Aug 21, 2023

Henry Hudson's exploration of Manhattan and the Hudson River changed the world, but not quite in the way he had intended. His pursuit of the elusive “ Northern Passage ” defined his career as a ground-breaking global navigator and took him on four documented voyages to find this theoretical shortcut to Asia over the top of the globe. But it would be Hudson’s unintended discoveries that would, in fact, be the most lasting. And included among these discoveries is the place that we now call “New York” .

This blog explores elements of Henry Hudson's biography, his nebulous career, tragic death and legacy, and examines the important lessons that we continue to learn from this historical anomaly.

Henry Hudson - Discoveries

Henry Hudson’s discoveries are remarkable not just for the accomplishments of a 17th century sailor in the absence of satellite technology or combustion engines, but also for the fact that his “ discovery ” of what would become the greatest city mankind would ever know, happened completely by accident.

The Hudson River

Henry Hudson’s “ discovery ” of the river that would come to eternally bear his name, was as inadvertent as his encounters with the Native Americans he met along that haphazard and schizophrenic voyage. And, in truth it would be those very encounters and not any of his intended findings that would lead to the discovery of the Island of Manhattan.

When the Englishman Henry Hudson was hired by the Dutch East India Company in early 1609, the specific purpose of this voyage was to find and successfully navigate the storied “ Northern Passage ” – a theoretical waterway shortcut to Asia over the top of the globe. The instructions from these staunch Dutch businessmen were as clear as they were concise – Hudson was to try the route “ above Nova Zembla (the top of Russia), towards the lands or straits of Anian (Bering Strait) and then to sail at least as far as the sixtieth degree of North latitude, when if the time permitted he was to return from the straits of Anian again to this country” (the Dutch Republic). And it was made clear in these instructions that Hudson was “… to think of discovering no other routes or passages, except the route around by the North and Northeast above Nova Zembla…that if it could not be accomplished at that time, another route would be subject of consideration for another voyage.”

In truth, before Hudson ever left the Amsterdam docks in April of 1609 in the East India Company’s 65-foot yacht called “de Halve Maen” (the Half Moon), he already knew that this specified route was impossible. Because he had already tried it…twice. You see, this 1609 voyage was in fact Hudson’s third attempt at this elusive shortcut to China , and from his hands-on experience and the information from his fellow explorers, including Captain John Smith and Bartholomew Gosnold , was that this passage was nowhere near the top of Russia, but rather on the western half of the planet – over the continent that we now call North America.

So, when Henry Hudson turned the Half Moon southeast and sailed over five thousand miles off his instructed course, he was not only defying his explicitly contracted directions, but he simultaneously set in motion a course of events that would eventually lead to the founding of the place that we call “ New York City ” today.

In disobeying his employer’s orders to “ to think of discovering no other routes or passages, except the route around by the North and Northeast above Nova Zembla ” Hudson took the Company ship across the Atlantic Ocean and into a series of encounters with Native Americans. These encounters started as early as Nova Scotia where on the tiny village of La Havre his crew, mostly Dutch sailors hired by the Company in Amsterdam, engaged in trading with the indigenous tribe, which ended tragically with a violent encounter that propelled this rogue voyage off to the rest of its North American exploration.

Upon reaching the eastern seaboard of today’s United States, Hudson’s ship then sailed as far south as Virginia, searching specifically for the inlet to this elusive “ Northern Passage ”. And after arriving at what Hudson already knew well was part of the English colony, he then turned the Half Moon around and headed back up the coast.

And it was on September 11, 1609 that Henry Hudson’s exploration, now into its fifth month, arrived at the river that would come to eternally bear his name. And when he entered what we now call the Upper Bay of New York, Henry Hudson was convinced that this majestic waterway was, at long last, the storied shortcut to China.

But much to his dismay, this channel did not in fact take him and his 65-foot Dutch yacht over the top of the planet, but rather to an increasingly narrowing section of the river at today’s Troy, New York, where the waterway narrowed into a diminishing stream. Now seven months at sea and with winter setting in, Hudson had little choice but to face the hard fact that this was not in fact the passage to Asia and sailed back across the north Atlantic. But Hudson himself would not return to Amsterdam ever again. He returned to London and entrusted his Dutch crew with the task of returning the Half Moon to the Company. As a result, Hudson was never paid the 800 guilders that the Company had contracted for him to pilot this voyage. Hudson neither returned himself, nor his charts and data to the Company. Because, in truth, Henry Hudson was never really working for the Dutch. Because he had been subversively working for the English the entire time.

The North American Fur Trade

In spite of Henry Hudson’s obsession with this elusive Northern Passage, it would have little to do with the navigational findings of this voyage that drew the subsequent interest of the Dutch. But rather, as a result of the crew’s casual trading with the North American natives, the Amsterdam businessmen were compelled to take a closer look at this land that Hudson’s mate Robert Juet had recorded as “Manna-hata”. You see, by trading inexpensive trifles – such as buttons and spoons or copper kettles -- the sailors received shiny pelts of beaver and otter, far finer than any such product available from the Russians, who had currently had a lock on the world fur market. This sudden opportunity compelled certain Dutch businessmen to quickly forget about the insubordinate Henry Hudson and refocus their efforts on this newfound territory, just above 40 degrees latitude.

But it would not be the Dutch East India Company specifically that would pursue this opportunity but rather a small, close-knit band of Lutheran businessmen living and working in Amsterdam. The group was led by a man named Lambert van Tweenhuysen and in spite of the ostensible “ failure ” of Hudson to find this shortcut to Asia, it was those shiny fur pelts that Van Tweenhuysen and his team were interested in. And so, they proceeded to invest in exploration back to this very river that Hudson had just returned from, specifically to explore and cultivate this potentially priceless fur trade. And the captain they entrusted with this exploration was the revered Amsterdam sailor by the name of Adriaen Block .

Hudson, however, seeing no value or future in this fur trade and remained thoroughly obsessed with his quest for this Northern Passage and by late 1609, had contracted for yet another voyage to find this elusive passage, contracting with another group of investors, this time back in London, for what would be his fourth and final attempt at this passage. This expedition which would leave England in early 1610, would in fact be Henry Hudson’s final voyage.

After nearly a year and a half at sea, his crew mutinied and Hudson and eight other crew members were cast off in a sloop (a large row boat) into the frigid waters of the ocean-like body of water that we call “Hudson Bay”[7] today. These nine were never heard from again and most certainly perished in the desolate and unforgiving waters. Among those nine was Hudson’s own son, thirteen-year old John Hudson.

Henry Hudson’s legacy

While his courage and tenacity cannot be questioned, Henry Hudson is no hero. A rogue explorer who increasingly proved that he was beholden to no man nor nation, Hudson and his crews engaged in multiple avoidable violent encounters with the North American native people. And while we cannot ever know the true circumstances of each of these tragic encounters, what we can do is compare Hudson’s behavior with that of subsequent explorers and settlers. And by comparison, the aforementioned navigator Adriaen Block had no such encounters with the natives of this land. In fact, Block would prove instrumental in forging an increasingly positive diplomacy with the native Algonquins that would prove pivotal to the progress not only of the cultivation of this fur trade, but of colonization here entirely. In many ways Adriaen Block was the great grandfather of American trade[7] and in essence, of the United States of America. Henry Hudson, in spite of his innovations and discoveries, most certainly was not.

Henry Hudson did in fact change the world …albeit inadvertently. His innovations served to not only inspire trade and exploration into the western hemisphere, but in fact served to catalyze the development of what would result in what we call “ the United States of America” today.

Embark upon a journey through the extraordinary Henry Hudson and the Discoveries of all those who followed him as we unravel his legacy and the lasting impact of his expeditions. The podcast Island explores this and remarkable components of our lost American history.

Describe your image

Henry Hudson North-West Passage expedition 1610–11

Why did Hudson's crew mutiny against him?

Henry Hudson was a well-known English explorer and navigator in the 17th century. He was the third explorer to search for the North-West Passage.

The North-West Passage was a fabled seaway linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans via the Arctic Circle and a sought-after trade route. The Virginia Company and the British East India Company, both keen to capitalise on the potential trade route, funded Hudson's expedition. It was to be his last ever voyage.

Hudson Strait and Hudson Bay

Hudson set sail in his ship Discovery in May 1610 and was swept by tides into what is now known as Hudson Strait, at the northern tip of Labrador, Canada. Pushing westwards, through ice-choked water, the Discovery reached the end of the strait six weeks later. Hudson then spent time mapping and exploring the area. In his journal he describes passing a narrow channel between two capes, which he named Cape Wolstenholme and Cape Digges, on what is now known as Digges Islands, both named after financiers of the voyage. From there he found ‘a sea to the westward’, today known as Hudson Bay.

Hudson then pushed south, reaching James Bay by 1 November 1610. Ten days later, the Discovery was frozen in and the crew became the first Europeans to spend winter in the Canadian Arctic. When the ice began to break up in the spring of 1611 the crew wanted to return home after a long, cold winter, but Hudson was resolved to continue with his quest, hoping he might find a westerly exit from the bay. The result was mutiny. On 23 June 1611, Henry Hudson, along with his son and some loyal crew members, were cut adrift in a shallop (a small boat for use in shallow water) and were never seen again.

The Discovery took the long journey home, losing many of the remaining crew on the way. The navigator was Robert Bylot, who would return in search of the North-West Passage several times, notably as captain of the Discovery accompanied by William Baffin in 1615.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

8 Henry Hudson Has a Very Bad Day, 1607, 1608, 1609, 1610

- Published: August 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter focuses on Henry Hudson's voyages of exploration in 1607, 1608, 1609, and 1610: the first two for the Muscovy Company of England, the third for the Dutch East India Company, and the last for the Merchant Adventurers. Hudson, English sea captain, had tried to sail to China across the North Pole in 1607, hoping to encounter an open polar sea, but ice prevented his success. Hudson also made two unsuccessful attempts to find a sea route through North America in 1609 and 1610. Given these experiences, Hudson might be considered a failure, but he saw possibilities for new sea routes and accomplished many things during his four attempts to find a route to China.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Search The Canadian Encyclopedia

Enter your search term

Why sign up?

Signing up enhances your TCE experience with the ability to save items to your personal reading list, and access the interactive map.

- MLA 8TH EDITION

- Hunter, Douglas . "Henry Hudson". The Canadian Encyclopedia , 09 January 2019, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/henry-hudson. Accessed 19 May 2024.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , 09 January 2019, Historica Canada . www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/henry-hudson. Accessed 19 May 2024." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- APA 6TH EDITION

- Hunter, D. (2019). Henry Hudson. In The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/henry-hudson

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/henry-hudson" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- CHICAGO 17TH EDITION

- Hunter, Douglas . "Henry Hudson." The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 02, 2008; Last Edited January 09, 2019.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia . Historica Canada. Article published January 02, 2008; Last Edited January 09, 2019." href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

- TURABIAN 8TH EDITION

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Henry Hudson," by Douglas Hunter, Accessed May 19, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/henry-hudson

- The Canadian Encyclopedia , s.v. "Henry Hudson," by Douglas Hunter, Accessed May 19, 2024, https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/henry-hudson" href="#" class="js-copy-clipboard b b-md b-invert b-modal-copy">Copy

Thank you for your submission

Our team will be reviewing your submission and get back to you with any further questions.

Thanks for contributing to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Henry Hudson

Article by Douglas Hunter

Published Online January 2, 2008

Last Edited January 9, 2019

Early Life and Career

Little is known about Henry Hudson’s origins. He was probably born around 1570 and in his late thirties when he began making his known voyages in 1607. He may have been related to a number of men named Hudson (sometimes spelled Hoddesdon or Herdson) who were associated with the Muscovy Company, a London-based trading enterprise. He had a wife, Katherine, and three sons, Oliver, John and Richard. Together they lived in London’s St. Katherine district.

First Voyage (1607)

Henry Hudson (with his son John) made his first known voyage in 1607 in the Hopewell, with a crew of 12. The voyage was associated with Sir Thomas Smythe, a leading figure in the East India Company. It was an attempt to find a passage through the Arctic, over the North Pole , to Asia. At the time, Hudson and others thought that the long summer days of the high Arctic might create an ice-free zone at the top of the world. Hudson was able to sail above Spitsbergen, one of the islands of Svalbard, an archipelago between Norway and the North Pole. This placed him beyond latitude 80° north, a record-setting effort, but the cold reality of Arctic ice made further progress impossible.

On the way home Hudson sailed about 800 km off course and in the process sighted a volcanic speck of rock north of Iceland that became known as Hudson’s Tutches. English whalers subsequently called it Trinity Island, while Dutch whalers gave the landfall its enduring name, Jan Mayen island. Hudson was probably trying to gather additional information on the feasibility of the Northwest Passage , which would lead to Asia through what is now the Canadian Arctic, as his course was taking him towards southern Greenland. Although he failed to reach Asia, Hudson’s exploration in and around Spitsbergen led to a new whale and walrus fishery.

Second Voyage (1608)

In 1608, Hudson sailed again in the Hopewell , again in association with Sir Thomas Smythe, but now with the aim of finding the Northeast Passage, a route to East Asia over the top of Russia. Hudson and his crew of 14 were unable to progress beyond Novaya Zemlya, an archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. The voyage was otherwise noteworthy for a remark in Hudson’s journal that crewmembers had sighted a pair of mermaids: one was “as big as one of us; her skin very white; and long hair hanging down behind, of colour black; in her going down they saw her tail, which was like the tail of a porpoise, and speckled like a mackerel.”

Third Voyage (1609)

For his third voyage Hudson was hired by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) to make another attempt at finding the Northeast Passage. He was provided a small, nimble vessel called the Halve Maen ( Half Moon ).

Hudson and the Half Moon , with a total crew of 17 (13 of them Dutch) left Amsterdam in April. He was no more successful in overcoming Novaya Zemlya than he had been with the Hopewell in 1608. Despite explicit instructions from the VOC to return home should he not find the Northeast Passage, Hudson made an extraordinary detour — all the way across the Atlantic Ocean, to the east coast of North America.

Hudson’s motivations are unclear. He may have made off with the Half Moon in hope of making a major discovery that could land another voyage commission. After crossing the Grand Banks , Newfoundland , Hudson had a dangerously close encounter with Sable Island before stopping at present-day LaHave , Nova Scotia , to replace a broken mast. There, Hudson met friendly Mi’kmaq , but after a few days a rift erupted between the English minority and the Dutch majority of his crew. A dozen heavily armed men, who were probably the Dutch faction, went ashore and “drove the savages from their houses,” according to crewmember Robert Juet’s journal. The Half Moon crew’s aggression may explain why in 1611 the Mi’kmaq took captive six men from a Dutch voyage that anchored at LaHave. None were ever seen again.

Hudson continued south to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and then briefly into Chesapeake Bay (an inlet between Maryland and Virginia), before turning north. He inspected Delaware Bay (between Delaware and New Jersey) before arriving at Upper New York Bay and the island of Manhattan. Upon entering Upper New York Bay he followed north the river that now bears his name. He probed 240 km of navigable water, all the way to present-day Albany, New York, before turning back.

Instead of returning to Amsterdam, Hudson sailed back across the Atlantic to the English port of Dartmouth. There he secured new backing for an English attempt at finding the Northwest Passage, and in July 1610 the Half Moon returned to Amsterdam without him.

Fourth Voyage (1610–11) — Exploration of Hudson Strait, Hudson Bay and James Bay

For his fourth voyage, Hudson was backed by a wealthy and influential group of men, including the Prince of Wales, and provided with the Discovery . The Discovery left London on 17 April 1610 with a crew of 23, among them Hudson’s son, John, and Robert Juet, who had been with him since at least his second voyage in 1608. Before he had even reached the sea, Hudson brought aboard another man, Henry Greene, to serve as a spy on the crew.

Provided with only a single ship and no messenger vessel, Hudson likely had only been expected to make a preliminary, one-season search for the Northwest Passage. But he sailed all the way across the strait named for him before turning south into a massive expanse of open water that also would bear his name. From Hudson Bay he probed still farther south, into James Bay , in which he sailed back and forth, “for some reasons to himself known,” according to one crewmember. In September, Hudson held an ad hoc trial of his mate, Juet, to air allegations that he was plotting to seize control. Hudson spared him from punishment, but replaced him as mate with Robert Bylot .

The voyage paused for the winter at the southern end of James Bay, probably in Rupert Bay. Remarkably, the Discovery crew endured the winter with the loss of only one man, but Hudson had a serious falling out with his shipboard spy, Henry Greene. In June 1611, after returning from a reconnoitering expedition in the ship’s boat, Hudson agreed to sail back to England. Before leaving, though, he replaced Bylot as his mate with another sailor, John King. The Discovery was stalled in ice on James Bay when a faction of the crew that included Juet, Greene and Bylot seized control of the ship on the morning of 22 June. Hudson, his son John, and seven other crewmembers (including King) were forced into the ship’s boat and cast adrift. They were never seen again.

Five mutineers died on the return voyage. Four, including Greene, were killed in a clash with Inuit at Digges Islands at the northern end of Hudson Bay; Juet died of starvation only days before the ship reached the British Isles. When the battered Discovery drifted into the company of a fishing fleet off the south coast of Ireland on 6 September, the original crew of 23 was down to eight.

Hudson’s third and fourth voyages ignited a flurry of exploration and trading activity. The Half Moon voyage led to fur trading opportunities for the Dutch. Dutch merchants were in the Manhattan area by 1612, and the colony of New Netherland was soon formed.

The French explorer Samuel de Champlain was told by a translator, Nicolas de Vignau, that Anishinaabe people at Lake Nipissing had secured an English boy from the Cree , the lone survivor of a wreck in the “northern sea” ( Hudson Bay ), and wanted to make a gift of him. The boy sounded like John Hudson and inspired Champlain to mount his 1613 journey up the Ottawa River . While the information Vignau provided was likely false, the failed 1613 journey led to Champlain’s more ambitious 1615–16 visit to Georgian Bay and the Huron-Wendat people.

Hudson’s explorations on the fourth voyage also inspired immediate follow-up voyages by the English in search of the Northwest Passage . Three survivors, Robert Bylot , Habakkuk (Abacuk) Prickett and Edward Wilson, participated in a 1612–13 voyage into Hudson Bay under Thomas Button. With William Baffin , Bylot made two significant voyages into the Canadian Arctic. Only after the final Baffin-Bylot voyage failed to locate the passage did Bylot and other survivors of the 1610–11 Discovery voyage stand trial for the murders of Henry and John Hudson and their companions. All were found not guilty in 1618.

- exploration

Recommended

Jens eriksen munk.

Sir John Ross

Navigation Navigation

Digital resources.

- Articles and Essays

- Historical Documents

- Site Reviews

- Book Reviews

- Student Works

- Bibliographies

- Annotated Links

- Famous People

- Newsletter Archive

The Twin Mysteries of Henry Hudson - His 1609 Voyage The Twin Mysteries of Henry Hudson - His 1609 Voyage

The twin mysteries of henry hudson—his 1609 voyage.

Introduction On September 2, 1609, the Dutch ship Half Moon sailed into what is now New York Harbor and anchored near Staten Island. For the next five weeks, the Englishman Henry Hudson and his crew of sixteen men explored the river that now bears his name. They traveled approximately 150 miles northward making contact with Native Americans and recording the observations that would eventually lead to the colonization of New Netherland. Then they returned to Europe, stopping first in England and continuing on to the Netherlands. End of story? Not quite, for two aspects of this voyage have puzzled historians and others for centuries.

The first mystery is why the Half Moon was in North American waters. The orders given to Hudson by his employer, the Dutch East India Company, were quite explicit: find a route to the Dutch East Indies (present day Indonesia) by sailing northeast past the northern tip of the Scandinavian peninsula, sail along the northern coast of Russia, and eventually enter the North Pacific Ocean via the Bering Strait.

The second puzzlement is that Hudson departed from Amsterdam and was expected by his sponsors to return directly there. In fact, part of his contract stipulated that Hudson’s family actually move to Holland and remain there until his return. Why did he stop in England first?

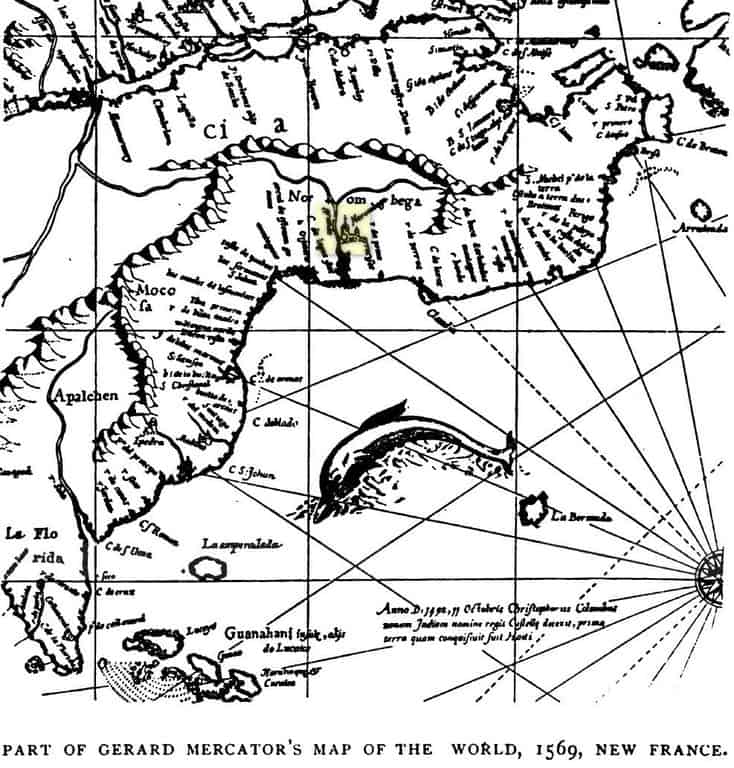

The Age of Discovery Before exploring the rationale for Hudson’s actions, a quick review of certain aspects of early seventeenth-century geopolitics is in order. Since the days of Portugal’s Prince Henry the Navigator, the Portuguese had a virtual monopoly on the southern trade routes linking the Far East with Europe. It was this trade that brought tropical goods, especially spices, silks, and cotton to European markets through Portuguese ports. The newly independent Dutch, seeking to avoid conflict with the Portuguese, decided to investigate the northeastern route to the Orient. The year 1609 also marked two important events: first, it was the year that the Bank of Amsterdam was established, an important part of the system of commerce then developing. This year also marked the beginnings of a twelve-year truce between Holland and Spain, thus freeing the smaller nation to concentrate on trade and exploration. In addition, in response to French explorations of North America, especially by Cartier and Samuel de Champlain, traders and men of commerce in England were also interested in alternate routes to the Orient. Indeed, John Cabot was sent to explore the North Atlantic shortly after the news of Columbus’ discoveries. Cabot was interested in the mythical Northwest Passage to the Orient. Although he was unsuccessful in finding such a route, it was suspected that traveling north or northeast past the northern tip of Norway might be ice-free for at least two or three summer months. Finally, it should be noted that this era was in the middle of what was known in the northern hemisphere as the Little Ice Age, a time when cold winters caused the canals of Holland to freeze for months at a time. (Remember Hans Brinker and his silver skates?) It is evident that this period of the mid-sixteenth century appealed to the adventurous spirit of those looking to the New World to satisfy their ambition. And Hudson was definitely one of these ambitious and courageous men.

Hudson’s Qualifications Almost nothing is known regarding Hudson’s education. He must have known how to read and write, analyze charts, and perform accurate readings of celestial navigation. His expertise in ship-handling in foul weather and unknown waters, and his leadership as a ship’s captain, are evidenced by the four voyages of exploration that he undertook. Hudson is known to have had direct contact with the foremost cartographers of his day1 as well as corresponding with John Smith, the leader of the Virginia Company’s colony at Jamestown.2 There is little known about how Hudson was able to secure the position as Captain of his first two voyages to the northeast; only conjecture provides any insight. Although no record of previous leadership has emerged, he was a seafaring man in his mid- to late-thirties; no one would have been named to lead such a perilous journey without either prior experience of command at sea or the influence of men of high standing in the circles of commerce or government. There is some evidence that Hudson’s older brother was at the Muscovy Company, which had been established in London in 1553. One co-founder of the Muscovy Company was Sebastian Cabot, the son of John Cabot, the explorer. Interestingly, another co-founder was one Henry Heardson. As the spellings of names were not exact at this time, it is possible that one of Heardson’s eight sons might have been Henry Hudson’s father.

From documents of the time, it is clear that Hudson was the captain of four voyages of discovery, two of which were prior to the voyage of 1609 and the last in 1610. His first two voyages on behalf of the English were unsuccessful, in that his ship was unable to penetrate the Arctic ice, or proceed further than the twin islands of Novaya Zemlya, in the Arctic Ocean north of Russia. Even though both voyages found his ship in these waters in mid-June, sea ice as well as ice in the riggings prevented further progress. The Muscovy Company, a private stock company looking for a route to the East, had sent Hudson on these trips. But after the second unsuccessful voyage, which may have included a mutiny by the ship’s crew in late 1608, Hudson found himself ashore with no immediate prospects for a ship or voyage.

The Half Moon Early seventeenth-century ships the Dutch used for ocean trade were built with a hold designed to carry approximately thirty to 100 tons of cargo and supplies, much of which was food and water for the crew. In size, a ship like the one Hudson used on his third voyage would not have been much larger than four inter-city buses parked two abreast. It would have had three masts and been capable of no more than ten knots of speed in optimum conditions. A minimum safe depth of water for such a vessel would have been two fathoms (approximately twelve feet). A typical crew would have been fifteen to twenty men. These ships did have a high stern and considerable freeboard along each side which made for safer sailing, even in stormy weather. And as demonstrated by the survivors of Hudson’s fourth voyage, a crew of six or seven sailors would have been able to keep her afloat. After this voyage, little is known of the Half Moon , except that five years later it ran aground and sank off the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, suggesting it was used for trade with the Orient.

The Dutch Connection Seeing no likelihood of a third posting as a ship’s captain in England, Hudson began to look to the Continent, specifically France, and then Holland for more opportunity. France was an early entry into the utilization of the resources of the New World, as evidenced by the explorations of Jacques Cartier in the first half of the sixteenth century. Hudson was able to use James LeMaire,3 a Dutch navigator living in France, as his agent to secure another voyage. And through Hudson’s acquaintance with Flemish mapmaker Jodocus Hondius,4 discussions with the Dutch had begun. These discussions were the first to bear fruit. With Hondius acting as interpreter, the contract for the Half Moon’s exploration via the northeast route to the Orient was signed in Amsterdam with two representatives of the Dutch East India Company on January 8, 1609.

The contract stated that Hudson would be provided with a vessel of about thirty tons (rather small for a voyage to the Arctic region) to depart on or about April 1, proceeding north and then east past Novaya Zemlya until he was able to sail south to about latitude sixty degrees. This location would have demonstrated that Hudson had entered the Pacific Ocean. Upon returning directly, he was to report to the Dutch East India Company’s director, and furnish all journals, logs, and charts .5 In addition, the contract stated that neither Hudson nor his crew was to enter into any other arrangement or employment agreement, and the captain’s wife and children were to remain as virtual hostages in Holland until his return. Hudson began to equip his ship for the voyage.

Juet’s Journal Robert Juet was an English sailor of considerable skill and experience. In addition to his seamanship, he could write. He kept the only firsthand and complete account of the 1609 voyage that has survived.6 He had accompanied Hudson on the 1608 voyage, which was unable to pass further than Novaya Zemlya.

Juet’s journal is a daily account of all manner of navigational, ship-handling, and other events, including position statements from which we are able to approximate the location of the ship at any time.7 Included in it are items such as sightings of quantities of fish and marine mammals, storms and fogs, birds (which indicate the ship’s proximity to land), as well as notations regarding the injury or death of crew members, sightings of land, etc. Because most of Hudson’s papers have not survived, Juet’s journal gives the most complete picture of the voyage.

The Voyage On March 25, 1609, Hudson and his crew of sixteen sailed the Half Moon away from Amsterdam into the North Sea. For almost the next two months, the ship sailed further north and east, only to encounter cold, ice, and storms. Quarrels and fighting broke out among the crew, and perhaps a mutiny ensued. The mixed crew of English and Dutch may have had different expectations regarding the voyage. The Dutch were experienced in warmer-weather sailing; the English, especially those who had accompanied Hudson on the previous voyages, may have been more accustomed to the cold. In any event, by May 19, the ship seems to have progressed as Far East as ice would permit. Juet’s log conveniently skips most of the first part of the voyage with the notation “because it is a journey usually known,”8 and so, if a mutiny was instrumental in Hudson changing course to the west, it cannot be confirmed. What is confirmed by Thomas Janvier’s work in the nineteenth century is that Hudson sought out Emanuel Van Meteren, the former Dutch consul in London, upon his return to England following the voyage to show him the charts and logs.9 Relying on information from Van Meteren, Janvier’s work states that upon encountering pack ice, Hudson presented two choices to his crew: either go to North America to explore an area north of Virginia, or proceed due west to explore the Davis Strait, the entrance to Hudson’s Bay. The crew agreed to the latter proposal, and after a watering stop in the Faeroe Islands, proceeded westward. At this point, it is important to note that if the above is true, namely that Hudson would allow the crew to set the sailing direction, he must either have lost control of the crew (as in a mutiny), or he had intended all along to ignore the Dutch East India Company’s directions.

Into North American Waters With the decision made to sail toward Davis Strait, the ship sailed slowly westward, losing its foremast in a storm on June 15. Gradually moving southwestward, the first landfall was Sable Island, off the coast of Nova Scotia. By mid-July, the ship was off the coast of central Maine, where Hudson took the opportunity to get freshwater, lobsters and fish from the local waters. By August 24, the ship, having skirted Cape Cod, was in the vicinity of Cape Hatteras. Interestingly, although Hudson was aware of his proximity to Jamestown and his friend John Smith, he made no attempt to enter the Chesapeake area. Four days later, Hudson entered Delaware Bay, but soon found the river too shallow to be a possible northwest passage to the Orient. On September 2, the Half Moon passed Sandy Hook on its port side and entered lower New York Harbor.

Exploring the River The Half Moon was to spend almost five weeks in the river. On the second day in the harbor, three rivers were sighted (possibly the East River, the Hudson, and a body of water separating Staten Island from Bayonne, New Jersey, which is still called the Kill Van Kull). The latter river was determined to be too shallow to explore, and Hudson used these first few days to send a small ship’s boat to take soundings to determine the depth of the waterways. On one of these trips on September 6, the Europeans were attacked by hostile natives and one crew member, John Colman, was struck in the throat with an arrow and killed. The men had to spend a stormy night in the bay; the next morning they were able to return to the ship. Later, Hudson led another party ashore, and John Colman was buried on a point of land, probably in Brooklyn.10