The Heroine’s Journey: Examples, Archetypes, and Infographic

By Julia Blair

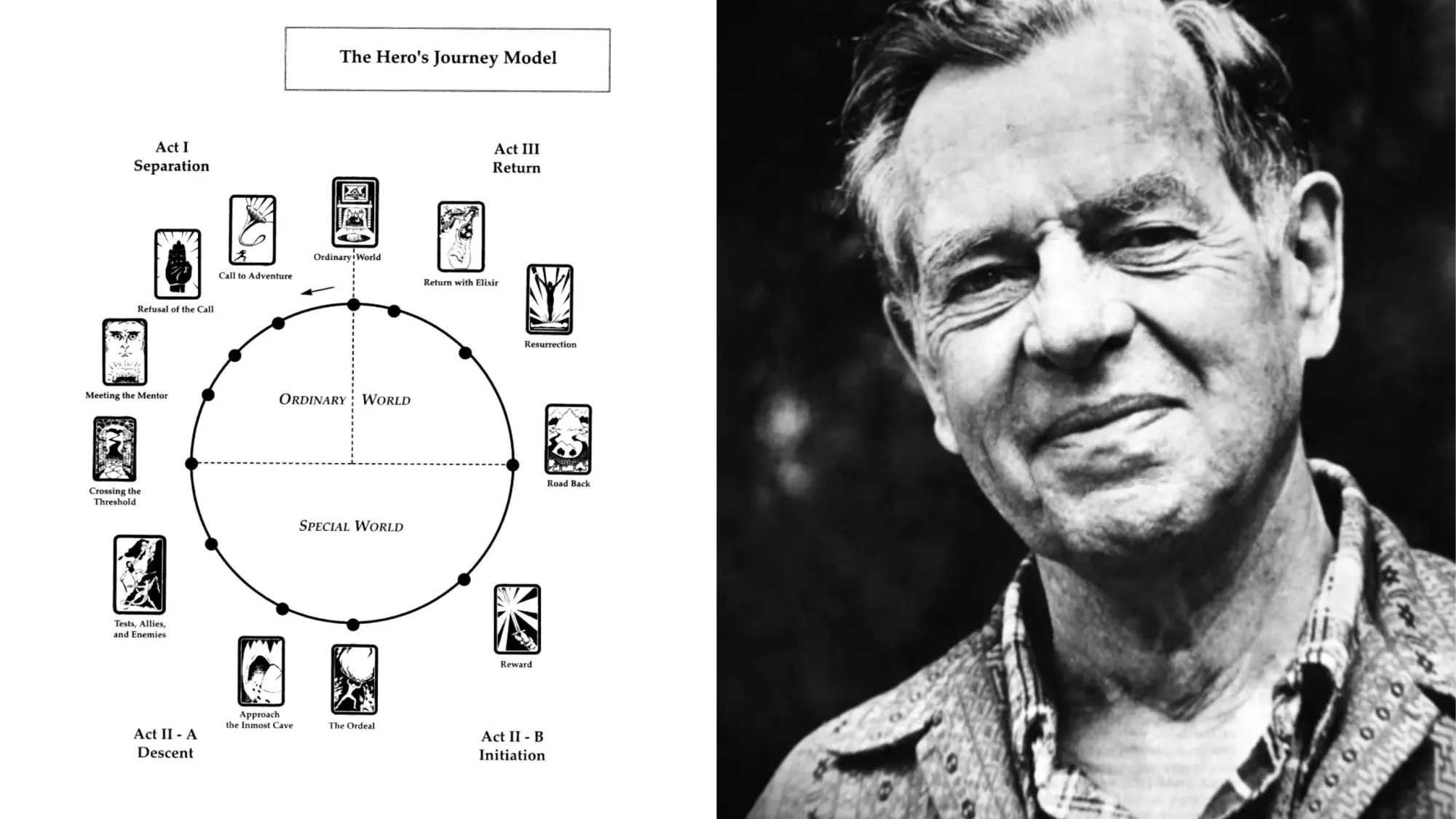

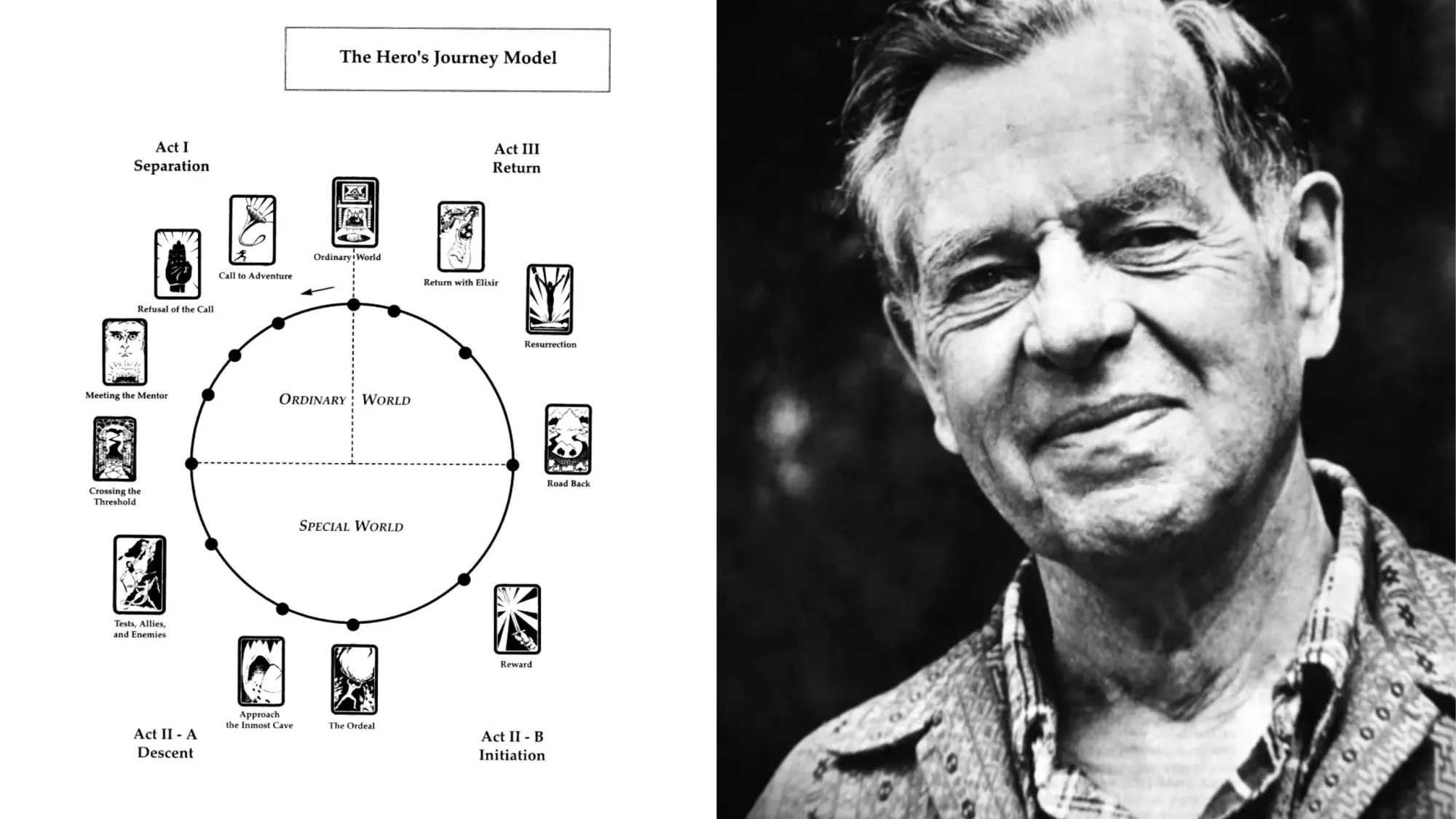

Joseph Campbell popularized the Hero’s Journey that has become a mainstay among writers. But he also said the symbols of ancient myths no longer fit the modern world. This is why we need to add the heroine’s journey to our myths.

Are you writing a Heroine's Journey?

Download our highly detailed infographic outlining the 20 major scenes you must have in every story.

We Need New Myths

Myths are archetypal stories that reflect our inner selves. They reveal our foibles and laud our innate strengths so that we can better understand our shared humanity.

But society has changed a lot since Theseus slew the minotaur.

“When the world changes, then the religion has to be transformed. The only mythology that is valid today is the mythology of the planet—and we don’t have such a mythology.” – Joseph Campbell

Campbell was right about our changing world. We face challenges our ancestors never even dreamed of.

- Technology revolutionizes our lives. We’ve transferred much of our making and thinking to computers. We socialize online. Memory is digitized.

- Societies struggle to cope with conflict and suffering based on socioeconomic, racial, and gender inequality.

- In business and politics, women are still subject to lower wages and discriminatory policies.

- The Earth itself is in critical danger as climate change impacts land, sea, and air, and alters the habitats of plants and animals.

In a recent tweet, Glasgow International Fantasy Conversations affirmed:

“The great theme of our age is one of loss. In a time of ecological crisis, we need stories. We need to imagine better tomorrows, stories as alibis that get us through the day.”

This failure of old myths to deliver answers is echoed in the very movie franchise that put the Hero’s Journey into popular culture.

In The Force Awakens , Rey exclaims, “Luke Skywalker! I thought he was a myth!”

She speaks for all of us in The Last Jedi when she implores Luke, “I need someone to show me my place in all of this.”

Luke reveals his disillusionment. “I only know one truth: It’s time for the Jedi to end.”

The loss of meaning in one’s life is painful to him—and to us, the audience—a feeling that echoes all too well our era of crisis and loss.

But when a myth becomes part of the collective memory, it’s remarkably persistent. We see that in the repetition of stories and movies based on the Hero’s Journey. The only way to change an outdated myth is to replace it with a better one, whose symbols make more sense and resonate with contemporary society. In this post, I’d like to look at alternative stories of self-discovery based on a pattern called the Heroine’s Journey.

A Female Perspective

Female action heroes like Wonder Woman’s Diana Prince and Divergent’s Tris rake in big bucks for Hollywood, showing that a woman can carry an action film and attract huge audiences. These movies stick to the basic shape of the Hero’s Journey, just replacing the male protagonist with a woman. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it’s the same old story dressed up in a new outfit.

In movies like Thelma and Louise , where women break the rules, the audience feels empowered. In this David and Goliath trope even when the heroines take freedom to the ultimate extreme, we feel that justice has been done in a fight against an unfair system.

In real life, women who push back against societal norms aren’t always seen in a positive light. “Nevertheless, she persisted,” originally meant to denigrate Senator Elizabeth Warren’s resistance to a male colleague’s effort to stop her from speaking, epitomizes how women who dare to challenge the patriarchy are seen. Intended to demonstrate, the catchphrase was transformed into a feminist call to action.

Psychologists, mythologists, and writers have searched for feminine alternatives to Campbell’s monomyth, one that gives women and disenfranchised protagonists the agency and power to carry stories that follow a different path to self-actualization. From this search, the Heroine’s Journey was born. But unlike the classic Hero’s Journey, there are multiple versions of a Heroine’s Journey. Let’s take a look at two of the best known.

Maureen Murdock’s The Heroine’s Journey

Maureen Murdock wrote The Heroine’s Journey as counterpoint to Joseph Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces .

When she asked Campbell about women and the Hero’s Journey, he famously responded:

“Women don’t need to make the journey. In the whole mythological tradition, the woman is [already] there. All she has to do is to realize that she’s the place that people are trying to get to.”

This reply inspired Murdock, a trained psychologist, to dig deeply into the realms of myth and psychoanalysis to develop an archetypal pattern of a woman’s quest for enlightenment and wholeness: the Heroine’s Journey.

You can trace the path of Heroine’s Journey in two popular stories. In the Pixar movie Brave, the protagonist Merida closely follows Murdock’s model as she struggles to make a place for herself without compromise in a fantasy version of medieval Scotland. And, notably, Zuko from the animated series Avatar the Last Airbender also follows a path that mirrors the Heroine’s Journey, which contributes to a powerful redemption arc of emotional depth and sensitivity.

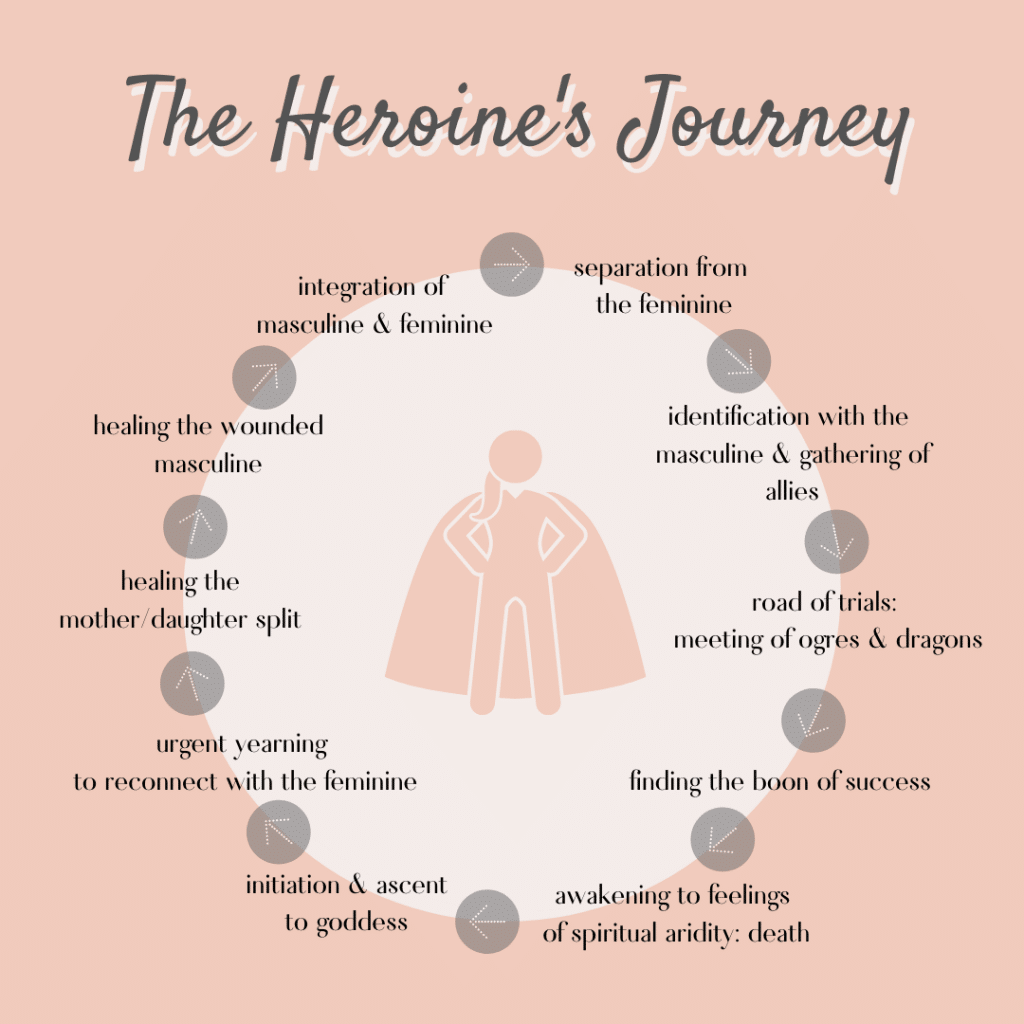

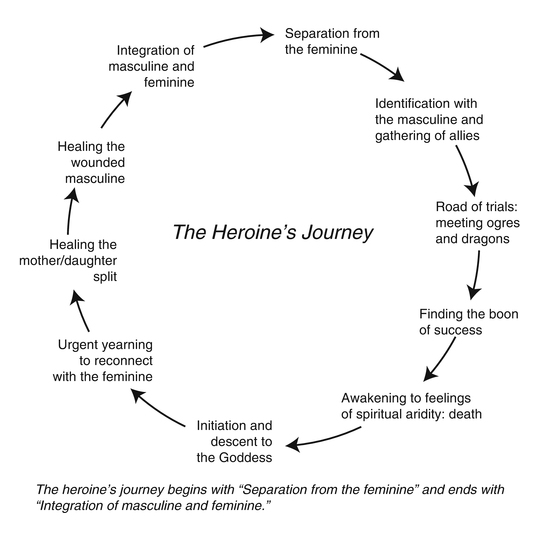

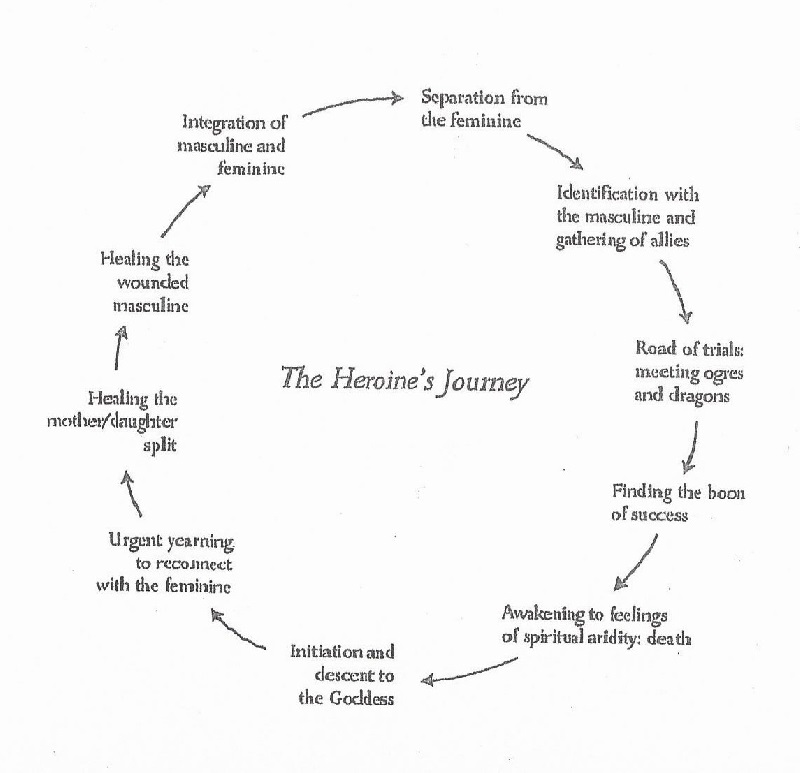

The journey includes ten stages, modeled here:

The Heroine’s Journey

1. separation from the feminine.

Women leave the nurturing shelter of the archetypal Mother behind. Some strike out in search of success and and a sense of self. Others flee from the negative associations of feminine behavior, wanting to be taken seriously and not unrealistically sexualized.

2. Identification with the Masculine

To flourish in a male-oriented world, successful women often emulate male behavior by abandoning the domestic sphere, suppressing emotional displays, and adopting male traits in the boardroom or on the campaign trail. Merida rejects traditional women’s activities such as needlework. She excels in archery, defeating all her potential suitors in a competition. Zuko is separated from the nurturing love of his mother as a child and thrust into his father’s world of domination through conquest.

3. The Road of Trials

The heroine confronts challenges and obstacles to her goals. She survives trials, earns degrees, or learns difficult skills. She must balance her personal and professional lives. She must prove herself to those who think she’s not worthy to succeed by male standards. Zuko chases the Avatar to restore his honor.

4. The Illusory Boon of Success

Having overcome her trials, the heroine attains a measure of success, a powerful title, position, or wealth. She is a superwoman who has it all. Imposter syndrome still sneaks in, and she wonders when she will feel she has truly succeeded.

5. Awakening to Spiritual Emptiness

Despite her successes, the heroine feels empty. She senses that there must be more to life. She may feel betrayed by the system or by her allies. She hears her inner voice after years of ignoring it. Even when he has returned home and regained his honor, Zuko finds the victory hollow. He questions his feelings and realizes that he has chosen the wrong path.

6. Initiation and Descent to the Goddess

The heroine experiences the dark night of her soul. She sometimes withdraws from friends and family. She no longer sees the point in struggling for success by her previous terms. The heroine must face her Shadow, an archetype that, simply put, represents the things within herself that hold her back from what she truly needs. She learns to be , not to do . Merida travels deep into a wild forest to seek help from an old wise woman or witch. The Wise Woman is a strong archetype in her own right, the dark face of the Goddess representing danger and wisdom.

7. Yearning to Reconnect with the Feminine

Having rejected the pursuit of outward success, the heroine may end associations with people or institutions that compromise her newly awakened spiritual growth. She turns to creative work and activities that enable mind-spirit-body connections. She begins to purify herself for the next stage.

8. Healing the Mother/Daughter Split

The heroine reconnects with her roots and finds strength in the past. She emerges from the darkness with a deeper sense of self. She is able to nurture others and be nurtured by them. She reclaims feminine traits she once saw as weak. Merida must draw upon her knowledge of the feminine activities she rejected in order to save her mother from an enchantment.

9. Healing the Wounded Masculine

Having reoriented her concept of femininity, the heroine must shed toxic perceptions of masculinity. If she has rejected her earlier pursuits in the male-oriented world, she searches for what remains meaningful to her. She casts aside unrealistic concepts of men. Having rejected his father’s (and nation’s) violent traditions, Zuko’s loses his firebending skills until he learns how to use them in positive rather than destructive ways.

10. Integration of Masculine and Feminine

Our heroine has come full circle. Male and female aspects of personality are integrated in a union of ego and self. She is whole and capable of genuine love for others. She remembers her true nature. Not until Zuko joins up with Avatar Aang, who represents the antithesis of violence, is Zuko able to integrate his dual nature and achieve wholeness on his own terms before bringing balance to the world. Merida, too, has learned to embrace the different aspects her life. She accepts the value of her mother’s instruction in feminine pursuits while retaining her interest in archery and other stereotypical masculine activities.

Murdock’s model has roots in the women’s movement of the Sixties and Seventies, with a generation who raised their fists against the status quo. She and her contemporaries had heavy cultural shackles to break. Their efforts enabled subsequent generations to build on and benefit from a growing acceptance of the equality of women.

The Heroine’s Journey described by Maureen Murdock is a quest for integration and healing. The circle closes with the union of male and female, representing a journey toward spiritual and societal growth.

Its real strength is found in its understanding of the duality of human nature. The yin-yang symbol incorporates dark in the light, and light in the dark. There is strength in our Shadow selves, but only when we face our personal demons does our Shadow step aside and let us move forward.

Murdock built her model as a path for introspection and self-awareness, not specifically as a tool for writers. Nevertheless, it is one of the most widely known versions of a female counterpart to the Hero’s Journey.

Kim Hudson’s The Virgin’s Promise

Author Kim Hudson describes the Heroine’s and Hero’s Journeys as “two halves of a whole.” Although The Virgin’s Promise portrays a feminine take on the search for one’s authentic self, it avoids limiting the gender of the protagonist. Viola in Shakespeare in Love exemplifies the journey with a female lead and Billy in the movie Billy Elliot , is a male protagonist following a similar path.

Hudson developed her model for writers, specifically screenwriters, so it’s structured in three acts and frames archetypes and imagery in storyteller’s terms.

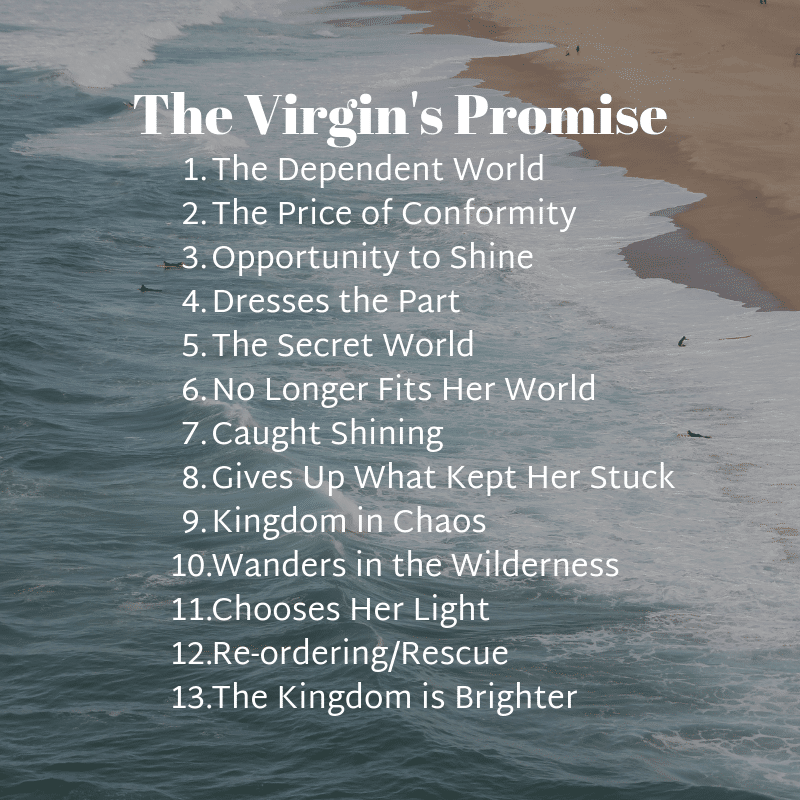

Some of the thirteen stages in this model have no equivalent in the Hero’s Journey. They reflect, instead, an inner emotional approach to life’s challenges. The thirteen stages are:

1. The Dependent World

The protagonist is tied to her normal world in order to survive, either by social convention, physical protection, or as a stipulation of conditional love. She is dependent on others to get by.

2. The Price of Conformity

The Virgin suppresses her inner gift to maintain the status quo. She may not realize she is captive in her Dependent World, or she may be critically aware of the need to hide her true nature. She may believe the low opinions others have of her and feel worthless. She is unable to break her chains or spread her wings.

3. Opportunity to Shine

A chance to express herself comes without risk to her dependent world. She may discover a talent, be pushed to it (fairy godmothers are great at this), or she may act in the interest of another person who requires her help. She recognizes a dormant part of her soul, or uses her talent in a new way.

4. Dresses the Part

The Virgin realizes her dreams may actually be within in reach. “Dressing the part” means she willingly steps into a role. In Shakespeare in Love , for example, Viola dons costume and becomes an actor. Cinderella wears a magical gown and goes to the ball after all. Sometimes, the Virgin receives an object or talisman that symbolizes her secret self. She “becomes beautiful” physically, metaphorically, or both.

5. The Secret World

Now she has a foot in the world of her dreams yet remains unwilling (or unable) to leave her old life behind. People might depend on her. She may be in physical danger, or fears the consequence of letting go of the Dependent World. Change is a hard thing. Who hasn’t hesitated before plunging into the unknown?

6. No Longer Fits Her World

As the Virgin discovers her true nature, she realizes her double life can’t go on. The risk of being caught increases. She may feel that she’s still an outsider in her secret world. Her behavior ranges from risk-taking to rejecting her dreams, thinking she can return to the way she used to be.

7. Caught Shining

The Virgin is revealed, exposed in one world or the other by betrayal or changing circumstance. Her secret is secret no longer. She may reveal her newfound strength by coming to the rescue of another. Ayla, in Clan of the Cave Bear , exposes her skill with a forbidden weapon by saving a child from a hyena.

8. Gives Up What Kept Her Stuck

Many things may hold the Virgin back: fear of losing loved ones, being hurt by a new love, fear of success or loss. Now she faces those fears and breaks the hold that others have on her. Sometimes the Dependent World vanishes and she finds herself on her own for the first time. She is her own boss, the mistress of her fate.

9. Kingdom in Chaos

In the wake of her assertiveness comes disruption. She has rocked the boat and changed the status quo by her rejection of the things that held her back. She has upset the old order and the Dependent World may come after her with all its strength in order to re-establish itself.

10. Wanders in the Wilderness

The Virgin faces her moment of doubt. Despite her newfound confidence, things don’t go as planned. Her belief in herself is tested to the max. Things might look very good back home, tempting her to give up her crazy notions of independence.

11. Chooses Her Light

But the Virgin eventually chooses to shine. She expresses her gifts in an imperfect world, accepting her flaws and her strengths. She gains new insights about the world she left behind. Power has shifted, and she now holds at least some of it. She can take care of herself and has become a self-actualized soul. But her journey doesn’t stop here.

12. Re-ordering/Rescue

The world readjusts itself around her. The Virgin broke ties with the Dependent World in Stage 8. Now she returns to her community. Her transformation makes the old world a better place. She reunites with people she loves who recognize and value her true self. She is no longer controlled by others.

13. The Kingdom is Brighter

Not only has the Virgin grown, but the world has also become a better place as a result of her journey. She integrates her inner self with the outer world. Hudson explains, “She has moved from knowing conditional love to unconditional love.”

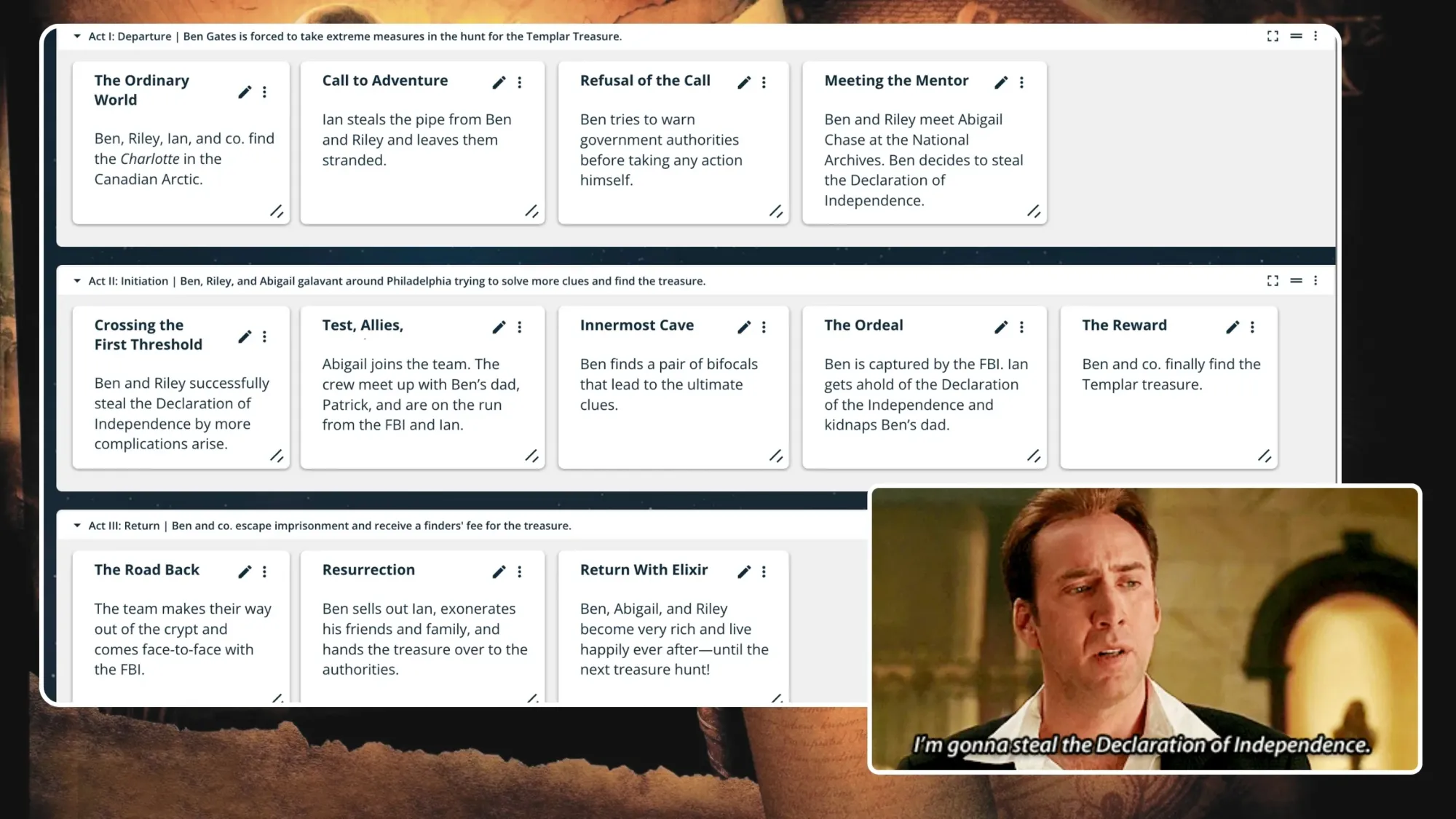

Shared Elements of Male and Female Archetypal Journeys

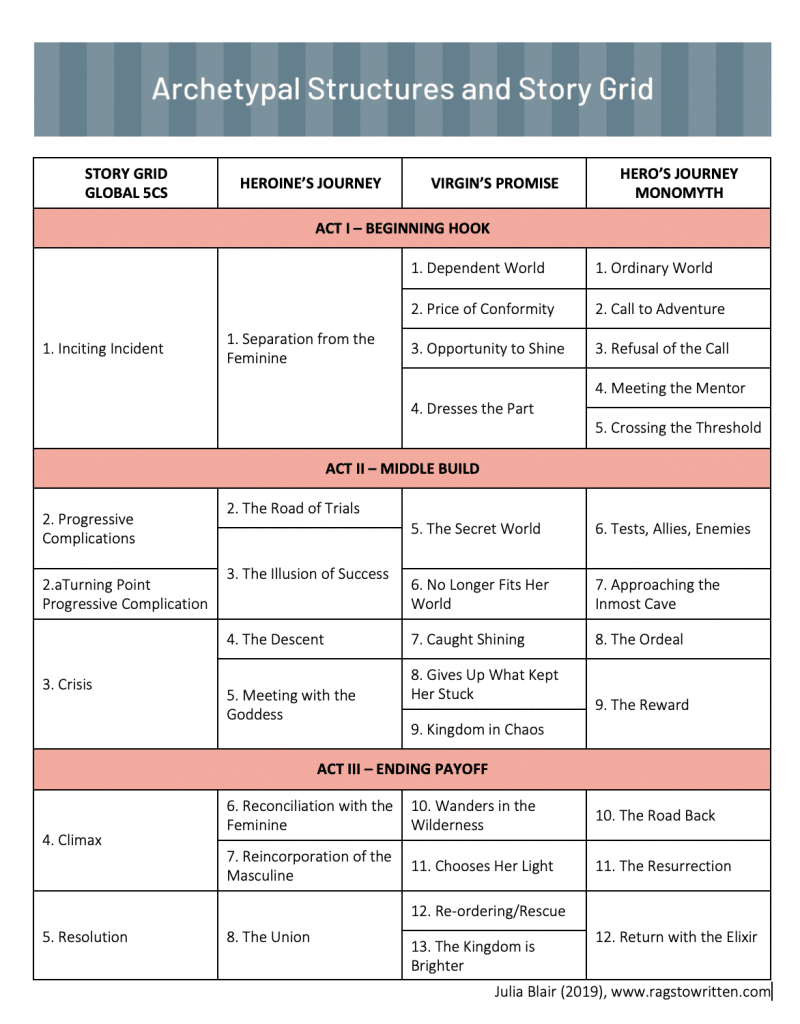

The Heroine’s Journey and The Virgin’s Promise show us what stories are like when women achieve their full potential. The Heroine’s Journey (HJ), The Virgin’s Promise (VP), and the monomyth (MM) share some elements, demonstrating that at least some components of heroic stories are universal:

- The protagonist rejects or suppresses part of themselves to fit in the normal world. HJ: Separation of the Feminine; VP: The Price of Conformity; MM: Call to Adventure, Rejecting the Call.

- The protagonist expresses new talent or knowledge without risking themselves. For a while, things look like they’ll work. HJ: The Illusion of Success; VP: The Secret World; MM: Tests, Allies, Enemies.

- The protagonist experiences a moment of doubt. They wonder if they have chosen the right path and if they can return to the way things used to be. HJ: The Descent; VP: Wanders in the Wilderness; MM: Approaching the Inmost Cave.

- Continuing on the journey, the protagonist does what they must to defeat their demons, conquer the adversary, or complete their quest. HJ: Reconciliation with the Feminine, Reincorporation of the Masculine; VP: Chooses Her Light; Wanders in the Wilderness; HJ: The Road Back, The Final Battle.

- The protagonist integrates their conflicting selves, rejoins the world, brings inner and outer balance. They have transformed themselves and the world. HJ: The Union; VP: Reordering/Rescue; MM: Return with the Elixir.

(The VP crisis occurs in Act III. In HJ and MM, the crisis takes place in Act II.)

You can download a printable version of this chart here .

Contrasts with the Hero’s Journey

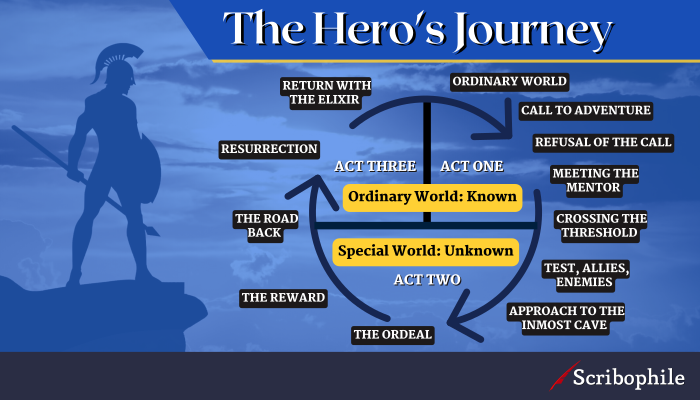

The male and female journeys of self-actualization follow different paths but arrive at a similar destination. Both trace a voyage of self-discovery, of confronting and breaking down self-deception and learning to integrate aspects of personality in positive, productive ways.

Heroine’s journeys are about self-worth and identity. The heroine brings balance to herself, then changes the world around her. It’s more about the journey than the destination.

The Hero’s Journey is a quest for an external objective. It is about obligation and rising to the task. The Hero seeks to right a wrong and bring balance to the world. In doing so, he is transformed.

One of the loudest and most legitimate complaints to be made about the Hero’s Journey is that it’s become formulaic. The constant barrage of mediocre action/adventure sequels out of Hollywood attests to that. I’m not saying it’s time to abandon the Hero’s Journey. It’s still capable of surprises. Star Wars’ Darth Vader arc gives us a failed Hero’s Journey and a fascinating character study. The Cohen brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thou delivers a twist on the classic with escaped convicts as heroes. As writers create new variations on a theme, the archetypal pattern is shifting.

Putting It To Work

If you read my post on archetypes , you know I believe that writers have the ability and responsibility to bring joy, hope and change to the world. Myths and archetypes are powerful tools for accomplishing that.

While reading about alternatives to the Hero’s Journey, I began to see that the Heroine’s Journey and Virgin’s Promise are more than just female versions of the monomyth. They meet the responsibility to spark change because they arose in response to a need for change.

Immutable Story Grid Truth: All good stories are about change.

All of them. Without exception. In every scene, sequence, and act there must be a change, or it’s not a working scene, sequence or act. Characters must change or fail.

The Virgin’s Promise and the Heroine’s Journey are different ways to achieve transformation. They’re alternative narrative structures that can breathe new life into the stories we tell and have the potential to bring some hope and joy as well.

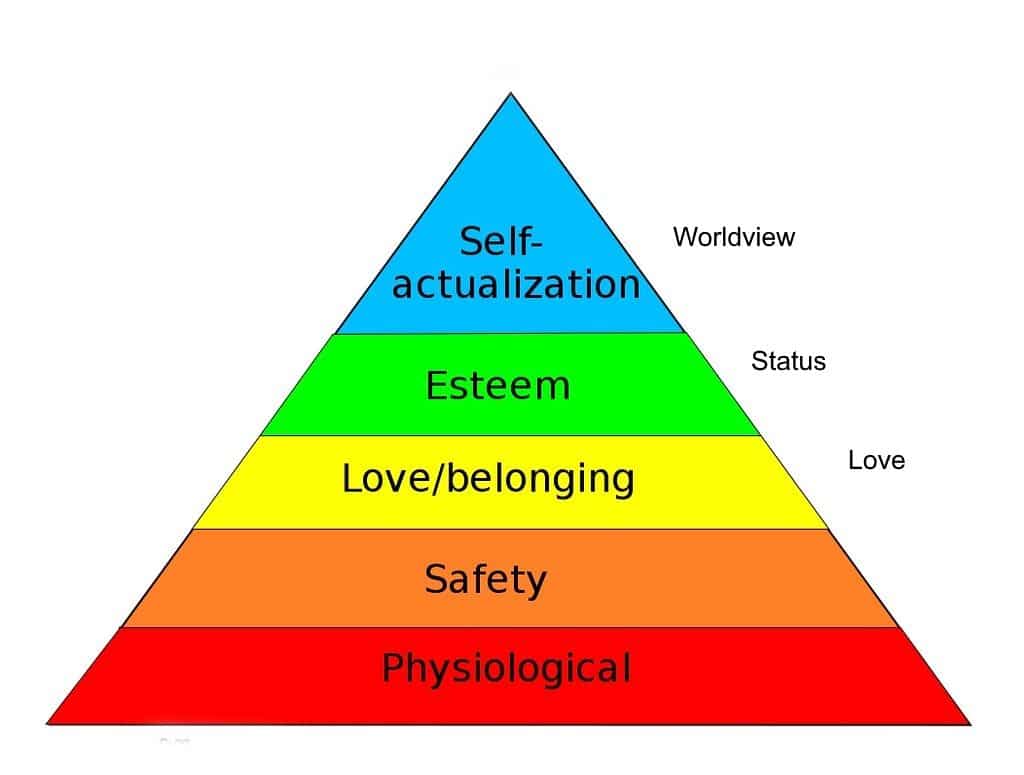

In Story Grid terms, these models relate to the higher ranges of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. You’ll find them especially good fits for the internal genres of Worldview (self-actualization) and Status (self-esteem). You can also find elements of these models in the Love Story, an external genre, when characters seek a mature and unconditional love.

MASLOW’S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS

Balancing internal and external genres within a plot is one of the hallmarks of a compelling story. Both Heroine’s Journey models enable us as writers to delve into the psyche of a character in a different way. They inspire new responses to the challenges of change and growth and the consequences of failing to change.

How might your current work-in-progress benefit by incorporating elements of the Heroine’s Journey?

Consider how your protagonist changes through the course of your story. Are they thrust into a situation that forces them to change whether they want to or not? Very often that’s the monomyth, and you can draw from the stages of the Hero’s Journey for inspiration.

Does your protagonist feel a growing dissatisfaction with the way things are? Are they faced with the realization that the problem is something inside them? Are they held back by external circumstance and lacking opportunity for their inner gift to bloom? You’ve got a great candidate for the Virgin’s Promise or Heroine’s Journey.

A Call To Action

Old myths are no longer as relevant in our complex 21 st century world as they once were, but we’ve not yet replaced them with something as strong and inspiring—and we need to. Campbell says that the most important purpose of myth is to guide humans through the stages of life, from cradle to grave.

Robert McKee, an authority on writing powerful stories, tells writers to write the truth. The truth is, we need desperately need new myths to guide us forward in a compassionate and enlightened way.

So where do new myths come from?

Mythologists don’t create our myths, they study them. They dissect them, examine the pieces, investigate symbols and themes. But myth is far more than just the search for meaning. It is the experience of meaning.

That’s precisely what happens inside a reader’s head when they read a book. Consuming stories gives readers the experience of meaning. Stories are how we deliver the new myths that the world needs now.

You, dear writer, are a mythmaker.

It’s our calling as writers to create new myths, to draw upon our experiences, uncover new symbols, and reinterpret archetypes.

McKee and others tell us that through story, people experiment with change without risking themselves. Readers and movie-goers try on different mindsets and personas, just like trying on clothes before a mirror.

When they find something that fits, a new way of thinking about themselves, the world, and themselves in the world, you the writer have made a change.

J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series taught me that there is no greater power in all the world than love. Masashi Kishimoto’s long-running anime Naruto taught me to never give up on my dreams. The Gate to Women’s Country , a novel by Sheri S. Tepper, taught me that going through a stupid phase doesn’t mark me for life.

The monomyth has roots in humanity’s psycho-emotional past. It connects us with ancient storytellers. And that’s not a bad thing. But there are other ways of knowing.

It’s time we looked to the future. You have a superpower that can change lives. Use it wisely, but use it.

It is time for us to imagine and write better tomorrows.

More Heroic Journey Resources

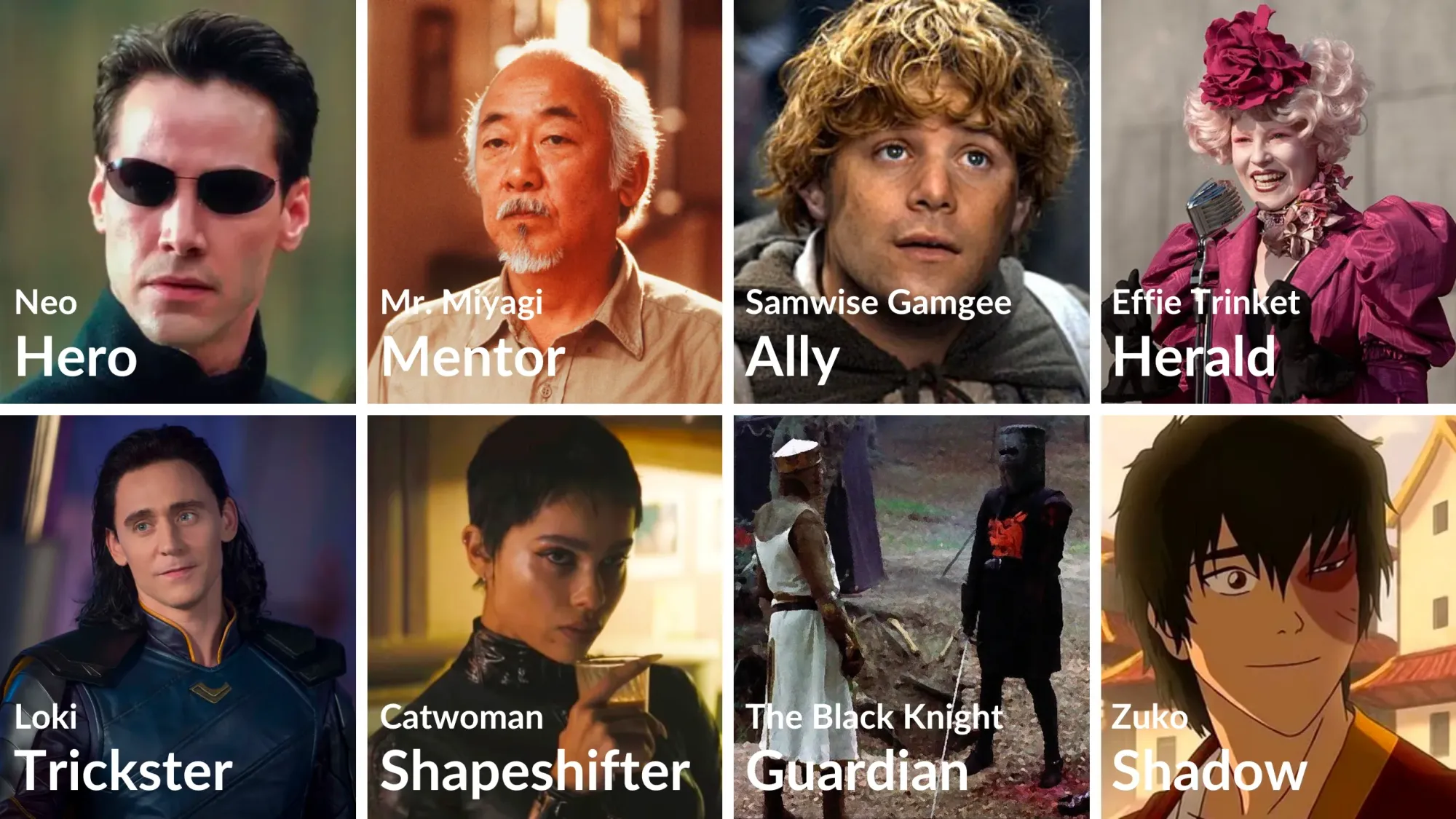

- Villain Archetype

- Hero Archetype

- Mentor Archetype

- Trickster Archetype

- Shapeshifter Archetype

- Herald Archetype

- Threshold Guardian Archetype

- Allies Archetype

I am grateful to Shelley Sperry for her insightful comments and assistance in making this a better post.

Share this Article:

🟢 Twitter — 🔵 Facebook — 🔴 Pinterest

Sign up below and we'll immediately send you a coupon code to get any Story Grid title - print, ebook or audiobook - for free.

Julia Blair

Julia Blair knows firsthand the challenges of balancing writing, family, and an outside job. Her most creative fiction always seemed to flow when faced with grad school deadlines. While raising a family of daughters, horses, cats, and dogs, Julia worked as an archaeologist and archivist. She brings a deep appreciation of history and culture to the editing table.

As a developmental editor and story coach, her mission is to help novelists apply the Story Grid methodology to their original work and create page-turning stories that readers love. Her specialties are Fantasy, SciFi, and Historical Fiction.

She is the published author of the short story Elixir, a retelling of fairy tale Sleeping Beauty, and has several several articles on the Story Grid website. She the co-author of a forthcoming Story Grid masterguide for the Lord of the Rings.

Level Up Your Craft Newsletter

The Heroine Journeys Project

Exploring and documenting life-affirming alternatives to the hero's journey, maureen murdock’s heroine’s journey arc.

Maureen Murdock

Murdock’s model, described in The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness, is divided into the ten stages:

- HEROINE SEPARATES FROM THE FEMININE. The “feminine” is often a mother/mentor figure or a societally prescribed feminine/marginalized/outsider role.

- IDENTIFICATION WITH THE MASCULINE & GATHERING OF ALLIES. The heroine embraces a new way of life. This often involves choosing a path that is different than the heroine’s prescribed societal role, gearing up to “fight” an organization/role/group that is limiting the heroine’s life options, or entering some masculine/dominant-identity defined sphere.

- ROAD/TRIALS AND MEETING OGRES & DRAGONS. The heroine encounters trials and meets people who try to dissuade the heroine from pursuing their chosen path, or who try to destroy the heroine.

- EXPERIENCING THE BOON OF SUCCESS. The heroine overcomes the obstacles in their way. (This is typically where the hero’s journey ends.)

- HEROINE AWAKENS TO FEELINGS OF SPIRITUAL ARIDITY/DEATH. The heroine’s new way of life (attempting the masculine/dominant identity) is too limited. Their success in this new way of life is either temporary, illusory, shallow, or requires a betrayal of self over time.

- INITIATION & DESCENT TO THE GODDESS. The heroine faces a crisis of some sort in which the new way of life is insufficient, and the heroine falls into despair. All of the masculine/dominant-group strategies have failed them.

- HEROINE URGENTLY YEARNS TO RECONNECT WITH THE FEMININE. The heroine wants to, but is unable to return to their initial limited state/position.

- HEROINE HEALS THE MOTHER/DAUGHTER SPLIT. The heroine reclaims some of their initial values, skills, or attributes (or those of others like them) but now views these traits from a new perspective.

- HEROINE HEALS THE WOUNDED MASCULINE WITHIN. The heroine makes peace with the “masculine” approach to the world as it applies to them.

- HEROINE INTEGRATES THE MASCULINE & FEMININE. In order to face the world/future with a new understanding of themselves and the world/life, the heroine integrates the “masculine” and “feminine” qualities/perspectives. This permits the heroine to see through binaries and to interact with a complex world that includes the heroine but is also larger than their personal lifetime or their geographical/cultural milieu.

Below is the journey laid out in chart form.

Heroine’s Journey Arc by Maureen Murdock

Share this:

57 thoughts on “ maureen murdock’s heroine’s journey arc ”.

Excellent summation of the book. Thank you.

Like Liked by 1 person

This misses the mark quite dramatically at nearly the first step. Note that the male hero’s journey sees no need to integrate the feminine into the character’s development. Essentially all you have done here is assumed that a woman requires a male persona in order to take part in the hero’s journey instead of developing a fully separate and unique approach to the journey. A woman’s heroic journey should not revolve around attempts to emulate the male one. Your idea that the first step must be to “Break from the societal prescribed roles of femininity” first assumes that femininity is socially prescribed, and that masculine traits are the true natural state of being. Second that masculinity is a required state of being for a heroic female character, rather than these traits being somewhat inherent (though subdued) as femininity is in men, and part of their natural progression. You can write a story in which a male or female has to integrate the opposite gender’s persona in order to overcome an obstacles, but this story will never be one that fully explores the depths of a feminine or masculine hero. Instead it will be one that just investigates the dichotomy between the two, and that is a very different story. You state that a truly developed hero’s journey for a woman would be a one in which she adopts outside forces of masculinity in order to develop. There should be no mention of masculinity period in a female hero’s journey. A woman has the natural capabilities to overcome her journey’s obstacles, without altering her inherent nature (at least in terms of feminine and masculine roles) Instead it must be her task to understand how to overcome her obstacles within the context of femininity, not outside of it. In a male hero’s journey, the central character must overcome obstacles as they relate to his inherent masculine persona, they never require integration of outside personas nor do they require deviation from their male persona. Their journey is built around the road from an unrealised heroic masculine persona to a realised one. Your first step must be to figure out what a female heroic persona is, independent of masculinity.

Like Liked by 2 people

Ark, thanks for your comment. There are many heroine journeys. The one cited by Maureen Murdock is used most often. When it features a female protagonist (or a non-male protagonist) in a male-define context in which the woman or girl is oppressed, abused, or suppressed because of gender, then often the first step is to break out of the restriction by adopting the skills (and sometimes the values or part of the values) of the “other” or male. However, in the heroine’s journey this is never sufficient (if it is, then it is a female protagonist completing a hero’s journey). Something falls apart, either her “success” doesn’t last, is attacked, or she finds it empty or insufficient– she then has to go beyond the male/female binary to seek wholeness/ satisfaction/ fulfillment/ purpose or whatever she is seeking. In other cases the binary may not be so overtly gendered. Perhaps a male is seeking a peaceful solution to greed and war (King Arthur in Once and Future King) or a couple is seeking an enlivened life apart from expectations of “success” in their families/suburbia, or a writer is seeking purpose that is not defined by fame, approval or monetary success. Usually the starting point is based on some kind of distress or longing and there is a background assumption that some kind of societal prescription is the means to success, even if the protagonist or narrator intellectually rejects it. The female heroic persona can be just as much of a trap as a male heroic persona.It is the falling apart of the binary as solution (both ends) that often forces the author/ protagonist/ narrator / life experiencer to seek a new coherency or paradigm– and this is the heroine’s journey. Stay tuned and keep writing. We are going to wrestle with binaries in some fall blogs!

You wrote-In a male hero’s journey, the central character must overcome obstacles as they relate to his inherent masculine persona, they never require integration of outside personas nor do they require deviation from their male persona.– This is interesting to me. I want to agree with this, but I do not feel it is accurate. There is a reaching out, a wisdom teacher must be found. This is seen everywhere in the literature that uses the Hero’s Journey as a template. This wisdom teacher is the Sophia, the feminine, the nurturing and holistic healer/wisdom keeper. It is always a man, sadly, in these tails, but these are whole men, at least. They are whole in that they carry their masculinity within the container of the womb.. it has been through a process of development which allows the balance the hero is looking for. We, as women, are so often hurt by the masculine. We cannot find where we are embodying that part of ourselves, nor do we want to. I believe, too, that we can find that wisdom teacher in a male, as well as a female-one that has done their work and can guide us to nurture in ourselves what needs to blossom through this experience. I have both male and female characters in my life that have found me and am so blessed. Their influence is the same in many, many ways. I feel guided and loved by each of them. I feel unspeakable gratitude for them and the process of becoming a whole, healed woman, who has finally found her voice and power in this world of brokenness.

The separation from feminine is what the heroine needs to learn from. She needs to learn that her femininity is vital by FIRST separating from it and learning that masculine traits by themselves cannot help her. It is a natural progression for a woman to want to separate from her femininity when she is in a society where masculinity is the only thing praised. At first, she may view herself as being subversive and strong by taking up a strong mantel and separating from society’s gender roles; however, the moral of this journey is that this is not the best way to counteract patriarchy, and that she must return to her femininity and female strength to succeed.

If she already knew this, and never relied on masculinity, there would be nothing for her to learn, and no point for a story or ‘journey’.

It would probably help if this was a society where a women being feminine WAS praised in any way. I mean, seriously, the only thing the entertainment industry does these days with female characters is Toxic femininity and men with boobs. This heroine’s journey reflects that.

Honestly, it’s rather frustrating that I can’t find an actually feminine heroine’s journey. The only time Masculinity is positive in women is when it makes a tomboy.

I agree that the dominance of the Hero’s Journey in our cultural messages and popular media is frustrating. However, there are heroine’s journeys if you look for them. Check out our post on the short story, Kicking the Stone by Barbara Leckie. https://heroinejourneys.com/2018/12/07/kicking-the-stone-two-sisters-and-a-relationship-a-trifecta-of-heroine-journeys . And more recently, The Water Dancer by Ta-Neshi Coates (which has a male protagonist) is ultimately, I think a heroine’s journey (which is one of its virtues) although for much of the book it teeters on the edge of a Hero’s Journey. I don’t know what you mean by men with boobs, unless you are referring to stories about gay men or transgender people. Certainly they are likely to have heroine journey stories because they are not part of the dominant culture and rarely become “the master of both worlds” and heralded as a leader in their life times. That is true of many minorities or members of a non-dominant group– including those with psychological profiles or profound life experiences that are uncommon or dismissed; the heroine’s journey is not restricted to sexual orientation or sex roles.

You make very good points: consciousness is a layered and fractal phenomena, and ultimately has its roots in a field of unstructured infinite possibility. All maps that speak to a surface structure and ascribe that structure to a culture (in this case ‘the archetypal culture of the feminine’), break down because they polarise and seek to balance opposites rather than integrate them. That is a function of conciseness not M or F, which are merely culturally ascribed arising from bio, psycho, social / contextual phenomena.

Great points, Paul. Although I think that calling masculinity and femininity or male and female roles and identifications “merely” culturally ascribed understates the penetration of these concepts have in our experience of the world– some of which is personal, much of which is community/society prescribed and constantly reinforced (and then seeps into our own ways of seeing the world), and some of which seems to have evolutionary underpinnings. We can, of course, push against the binary and characteristics associated with a M or F role, and to the extent that seeing the world, another person, or ourselves as masculine or feminine is used to delimit or dismiss personal experience or the possibility that a person can enact any and all traits/roles, we should.

NBALLARD: A “man with boobs” doesn’t refer to transgender or gay men, no. It’s a common trope in Hollywood and Literature where they write a male character and then cast an actress so that they can claim their diversity quota. If you can interpose a man with the “female” character and nothing changes as far as the story is concerned except the romance is now gay, then you have a man with boobs.

I see. Thanks for clarifying. Do you have an example of when this has been done? In my own experience, I have heard more often of editors asking that girl characters be turned into boys (in chapter books and YA books) because boys read boy books and girls read boy books but boys (supposedy) don’t read girl books.

Thank you for posting this. I was immediately uncomfortable and disappointed with Murdock’s heroine journey arc. I’m looking out for an alternative. I would love some suggestions as to where to look. I can see that part of the initial difficulty is that much of the mythology that Campbell looks to is from patriarchal societies. Murdock’s, it seems to me, is a second-wave feminist response, instead of being based on matriarchal mythology, but possibly that was the point.

If the Murdock heroine’s journey doesn’t fit the story or experience you have in mind, check out Virginia Schmidt’s version and also the Healing Journey and the Journey of Integrity, all on separate pages in this website. Several of them also have blog post explanations. We are also working on a Seeker’s Journey, so stay tuned. Note: some journeys are based on myth (archetypal psychological yearnings) and some are post-myth journeys (grounded in contemporary non-dualistic multi-national diverse and/or non-magical thinking).

I’m very late to this conversation, but I feel that I have to comment that I don’t really agree that the male journey does include the feminine. From a Post-Jungian perspective, achieving the hieros gamos through embracing The ANIMA is central to the Inner Journey of the hero.

I feel historical context is also important. For those of us around in 1990, this was monumentally new and life-giving. It’s easy to look back 30 years and criticize the pathfinder. We can continue to study, however, look for weaknesses and continue to grow. All knowledge is built upon the shoulders of the pathfinders before us.

Where you see gaps, do the work and fill the gaps. Be a new pathfinder.

This is very helpful. I think the woman’s journey today includes the stages of Hero’s Journey of Joseph Campbell ( in the Identification with Masculine stage) but then moves beyond it at the end to re-connect to the feminine so as to move to a deeper intuitive understanding beyond any one time, person, culture, race. This is a timeless connection.

Like Liked by 3 people

Excellent. Thanks for doing this work!

Delighted to find you and this charting of a woman’s journey. I have my own experience of Campbell and have been finding/telling heroes’ stories for over 30 years . I once asked him if he knew of any stories from all his research in which a man and woman stayed together, worked together. He was silent a long time and then said he could only think of the old couple who lived by the side of a road and cared for travelers. Thinking back now on conversations with him, I’d say he was of his time, that he delighted in and was amused by women, but definitely believed that we’re here as sidekicks to men. At best.

Thanks for your comments. If you would are interested in other examples of people staying together, our team might be able to find some for you.

I would be interested in finding some examples like that.

we are working on a couple of blog posts that illustrate people’s loyalty to one another as part of a heroine’s journey.

I think of my own story of rowing across two oceans with my late husband as an example of people staying together. I’ve also thought a lot about my late husband’s take on our rows as Campbell’s hero’s journeys while my own take on our rows is something quite different. I’m not even sure Murdock’s model works for me because I am still in the process of charting what those journeys really were for me. In my recently published memoir “Rowing for My Life” I explore this as a couple. I know there is another story to be told of my journeys alone. Happy to find this blog!

Thanks for sharing your story, Kathleen. We’d love to here more about your journey and what you believe the differences are between your husband’s view of the journey and your own.

I consider my two rows across the Atlantic and South Pacific oceans with my late husband, examples of a couple staying together after the journey. I believe he saw our ocean rows from the POV of the hero’s journey while I saw it from the feminine journey POV. I just put up a post on my blog site about this. My recently published book on our ocean rows, “Rowing for My Life” illustrates this too. I’ve enjoyed the readings on this blog!

So interesting – I’ve always had a sense that the female journey is different from the male journey, but have in the past simply adapted the Hero’s Journey. The Heroine’s Journey has opened up the possibilities considerably in my WIP. Thank you!

One critique — number 4 is the ‘Illusionary’ boon of success, and that one word changes the entire meaning of that stage of life.

Food for thought.

Hi Luke, thanks for your comment! I agree that step four’s boon of success feels illusory, but usually only after one achieves some measure of success and it fails to provide the “boon” one had expected. E.g. the promised paradigm shift or ongoing fulfillment doesn’t materialize. It is the failure of the boon to stick (e.g. the failure of a happily-ever-after or change in community attitudes) that catapults the subject toward step five and ultimately the rest of the journey.

No. To be brief, in the book itself, the word illusionary is literally that. I feel that the omitting of that word in the list of ten steps is something (for you) to think about.

But that is the point, isn’t it? Maureen is saying that you deceive yourself about the ‘illusionary boon of success’ you are experiencing. Because it is not actually who you are, it is not what the voice inside wants, it is not what the person you keep locked up inside wants… whatever it is – it is not what your true self wants. So your success in life up to that point, even if you are a successful person, is ‘illusionary’ – not that it ‘feels’ illusionary, it *is* illusionary. And after you realize that, and make changes, then you are past the ‘illusionary boon of success’ and on to the next step of life.

since this is the internet, want to mention I write this without spite or malice. I just had a coworker randomly ask if I felt fulfilled at the job where we work together, and I couldn’t help but think about Maureen and the steps that women take in their lives. My coworker asked that because earlier in her life she wanted to work at a nursing home but said she selfishly chose other things. My coworker is currently under the ‘illusionary boon of success’. If all women are on the same path, or experience the same steps in life, as Maureen and other suggest, well that was my initial point in my post a year or so ago, that you too are in that stage/step, and hence purposely omitted the word illusionary.

Good luck with love.

Brilliant! This makes sense of the woman’s attempts to individuate from mother-figure—reveals the complexity of this effort. Thank you!!

Can you give us an example of a heroine Journey history, tale, or movie to understand it better?

Hi Matus, We have given lots of examples already on the site. Go to Journey Narratives and look at the drop down menu for movies, folk tales, short stories and novels. Here are are few more: Our Souls at Night by Kent Haruf (novel); Random Family by Adrian Nicole LeBlanc (creative nonfiction/reportage); and Department of Speculation by Jenny Offill. We will probably be doing a review/exploration of each of these books (plus movies) and more this fall. So stay tuned!

Thank you for your summary. I am interested in exploring more of the binary of masculine/feminine. Identifying as a queer person, I see this binary as an inherently heterosexual one, and one which I do not relate to (nor do many people I know). Are there ways in which a journey could be made which do not divide us a category of two? Warm regards, Anna

One of the things I like about the Heroine’s Journey is that it is oriented toward wholeness, not win/lose/; success/failure; good/bad; male/female; leader/follower gay/straight, and other binaries. Wholeness is often conceived of as the integration of two opposing forces or ideas, but it need not be. You raise a very good point and I will try to integrate the idea of wholeness as something other than the integration of binaries into some new posts coming this fall. Part of the temptation to see life or purpose as a yin/yang binary is that many of our brain functions operate as binaries, but that is no excuse. Thanks for your comment and please keep coming back. If you have another conception you would like to offer as a blog or extended comment, by all means let us know. And we are glad you stopped by. Come again!

I am preparing to finalize an article regarding Haya’s journey on the first book of my Immortals series, The Sylph’s Tale. like this article and I am currently taking a class on Mythology that is the best, in my opinion, I have taken.

Wow! Just found your site and it’s very helpful. My wife just completed all her training to be a firefighter in our town. I am trying to be as supportive of her as she has been of me during my career. Unfortunately I am supporting her from my male perspective. I want to try and understand her ‘heroine’s journey, from her perspective. Your site may be very helpful indeed. Thank you!

Does the Monomyth need to be rewritten to be gender specific? Not in my opinion, I respect an attempt to tailor a gender specific guide to Campbell’s monomyth but I think it moves further from the barebones structure which allows it to resonate despite gender, time, class. To add to what has already been succinctly reduced seems counter productive, and introduces an exclusivity at odds with the original intent for universality. It’s the Problem Solver’s journey, in essence, and each step is vital to any gender who seeks to solve a problem or test the merit of a challenging idea. I agree the Monomyth can be tailored based on gender of protagonist when implemented into a narrative, but that would only be filling in the spaces between steps, not including those beats into the native template as some kind of be all and end all to interpreting the monomyth to fit gender, well that seems boldly presumptuous and potentially regressive to me. But what would I know?

Hi James, Neither the hero’s journey nor the heroine’s journey is gender specific. Nor do I believe there is one myth that encompasses the entire human experience, although there are myths that appear in multiple cultures. Indeed, the Hero’s journey can be characterized as the “problem solver’s” journey, but it ends when the problem is solved, and life is not a single problem that can be solved, either at the individual, group, country, or humanity level. The beginning of the heroine’s journey is similar to the hero’s journey, but it goes on after the “boon of success” — as life does. Many stories end with some boon of success– winning the Olympics, obtaining the treasure, getting the job, getting Union recognition for one’s fellow and sister workers, etc. but that doesn’t mean the real life experience would end there. We human beings like the idea of one problem being solved that would solve everything “once and for all” but we believe the real journey of life is longer and more complicated and requires multiple perspectives and patience. Of course, one can approach the next problem as the “real problem” that, if solved, will truly solve everything once and for all– and this accounts for so many hero’s journey sequels that are new hero’s journey and, of course, make room for the next sequel which is another go-round of a problem that repeats the same steps over again. Stay engaged, read more of the site, it’s good to hear from you.

Story – a test to evaluate the merit of an untested or challenging idea Shadow – represents the challenging idea that demands to be reconciled Herald – represents the most recent failed attempt to reconcile the idea and latest data set on the challenging idea, and calls for more Champions to attempt to reconcile. Champion – represents the successful tester and one who finally reconciles the idea, to decide whether the idea should be abandoned or integrated, accomplished via submitting to the idea with full empathy while relying on Sidekick (un-coerced support) to escape if overwhelmed (control for peer bonding reinforcement), and allow for a decision to be made to banish Shadow from hosts through enlightenment or else integrate Shadow with existing system of order to constitute final reconciliation if deemed worthy. Sidekick – represents the data set for the system of order with which the challenging idea must be reconciled, and tests the idea in respects to peer bonding reinforcement and sustainability across domains (mental, community, ecosystem at large) Mentor – expands data set on reconciling the challenging idea, ensures test parameters are met Trickster – expands data set to control for perception bias (subconscious limits) in idea appraisal (the jester, half blue, half red, spins purple in your head) Shapeshifter – expands data set to control for perception bias (projection) in appraisal of idea integration across domains (mental, community, ecosystem at large) Threshold Guardian – control for ensuring test parameters are met to facilitate a reliable result over the course of the test (narrative)

Meeting With The Goddess – defines parameters to be met for net positive outcome versus the parameters for net negative outcome. Atonement With The Father – addresses the previous inabilities on the part of the system of order to reconcile the idea, to better reconcile future challenging ideas via continued process update and redesign, and in turn, system of order update and redesign, to continually seek equilibrium across domains. Making Allies/Rescue From Without – control for Champions who try to validate an idea while overlooking its peer bonding reinforcement value. Returning with the Elixir – ensures the idea is reconciled, either through integration or abandonment, once investigation is done and knowledge claimed, to facilitate the final implementation of a sustainable solution, and serves as a control for Champion’s that may try to use the claimed knowledge of the Shadow to wield power over others rather than reconcile it. Master of Two Worlds – not the individual, but rather the solution, is elevated to “king of all lands”, allowing all people to live free from the previously un-reconciled idea (Shadow).

rush not in understanding, lest presumption leave you blind

Hard to disagree with this, although I might say, rush not to conclusions, lest presumption leave you blind. It’s hard to rush to true understanding– although sometimes it comes upon you in a rush.

Hi Sam, Good to hear from you. It sounds like you are exploring the hero’s journey/ heroine’s journey / life’s journeys through a game– the Monomyth game??? The categories you cite are intriguing and play a role in many stories. We’d love to have you write a blog for us on your analysis of the board game’s journey arc (or arcs). Many of the concepts have an analog in cognitive science that would be interesting for us to explore if you laid out the game concept a little more. (Or we can look at the game, if it’s a physical game board if you would prefer). As we have repeated said thorughout the site and our comments, neither the hero’s journey nor the heroine’s journey is gender specific. They often are launched by different catalysts, but boy, girl, many woman, trans etc. can go on either journey (and we all usually have experiences with both although we may not recognize it).

The Champion’s Journey (non-gender specific) – a list of checks and balances to prepare a human psyche to be able to judge the true merit of an idea which remains un-reconciled, through reliable determination of the potential impacts it has upon integrating across domains.

The Boon is the gaining of the sword of knowledge that allows a Champion to parse the negative aspects from the positive aspects inherent to an idea, and the journey to claim the sword requires they have also learned “true sight” to be able to fully understand the idea (unhindered empathy), and thus its potential positive/negative impacts across all known interconnected domains (systems of order) as explored on their journey beyond their original domain threshold.

The Champion is also required to have learned to remove their perception bias to ensure a reliable determination on where to parse the negative from the positive aspects inherent to the idea in respects to how it will potentially affect all domains.

Finally, the Champion must be proven able to serve the benefit of all through their actions, so as to not be tempted by the Illusory Boon (selfish use of the elixir) vs Ultimate Boon (elixir for the benefit of all).

I offer none of this in rebuttal, but to implore the universal underlying structure of the Monomyth be recognized and not compromised upon extrapolating for the depiction of gender specific Champions, but rather reinforced.

There are 18 stages to the Monomyth (the game board), with the story (rules of the game) consisting of 8 key archetypes each with a unique function, which reinforces the rules of the game and the relevancy of those rules to the game board. It seems this is often overlooked in understanding the work of Campbell..

Regard, Sam

I don’t think you need to worry about recognition of the underlying structure of Campbell’s monomyth– we have spent hundreds and hundreds of hours analyzing it in every form. Do read the entire site and I think it will be quite clear to you that neither the hero’s journey or the heroine’s journey is necessarily gender specific. Read, for example the two-part blog on Canadian Residential schools for a non-gender specific analysis. As noted in response to your previous comment, we’d love to have you do a guest blog analyzing the game to which you refer and the eighteen stages that seem to be part of the game. I leave you with one final thought– remember, myths are myths– not actual life experiences, and archetypes are simplified versions of aspects of people— and no single myth or archetype can explain either life or a person, but they are often helpful in shifting our perspective to look at our lives and selves in new ways.

The prince/castle/dragon/princess metaphor simply represents the elevation of the trait of being an “unselfish Champion who offers sustainable benefit to all” which evolution tends to select for.

That people easily agree on this being a positive trait to express is evidence of its universal “truth”, and is not gender specific, but specific only to those who would solve emerging problems of an unknown nature that yield a boon that has potential to help all if not kept selfishly.

Perhaps that this domain was once held by predominantly by men is what has colored the genders within the metaphor to date, but the metaphor holds true gender roles swapped or even homogenized, it is simply the point of the metaphor that it is important, not the gender’s involved. Especially with LGBTQ story telling, the prince/castle/dragon/prince or princess/castle/dragon/princess metaphor should continually strive to yield the same metaphor result, as it is my hope this shall hold true despite the ever changing landscape of human reproductive capabilities that awaits us.

And this final overture I offer, that what I have written and is awaiting moderation may yet see the light of day –

I think what you offer on this page serves as a really helpful insight to implementing the Problem Solver’s Journey for a would be Problem Solver who lives in a society that is plagued by a problem yet their ultimate savior and Problem Solver is denied entry to Problem Solving via a system wide prejudice toward them, and that may subsist across domains, and for which the solution should be implemented at the Atonement With The Father stage, (or else go un-reconciled as would be expected in a cautionary tale, or in tale of a lesser Champion who rids the world of some shadow, while living under another, and come tale’s end is still awaiting a Champion to set them free from the Shadow of “prejudice” which continues un-reconciled.

To say that the metaphor should perhaps always include multiple shadows to reflect the real world in which we live, and that it would be okay to allow such a “prejudice” shadow to not be reconciled (as opposed to banished where it eternally lurks in threat of resurgence) to become routine, would be to begin to complicate story metaphor’s to a point where potential allegories become difficult for younger minds (or any minds) to extrapolate.

I simply ask here that it be recognized, albeit as valuable as the work on display here may be, that it not be at the expense of any misunderstanding or derision to the true value underlying the Monomyth.

Blessings and best wishes be to you, and to any who may read this.

Kind regards, Sam

Hi again Sam, interesting comments. I resist the idea that we have an ultimate savior or problem solver– although that is sometimes the impression that the Hero’s Journey can leave on with. But certainly there are problems to be solved (which lead one to see new problems, or the solution creates a new problem, etc.) and both the hero’s and the heroine’s journey and other journey arcs can help us to see problems, solving problems, and problems that resist “solving” in new ways. See comments below, if you’d like to expand upon the themes in the board game you describe for us in a guest blog post.

This arc meshes beautifully with Grace by Paul Lynch which I am teaching this term. Grace must dress and act like a boy to survive the great hunger during the potato famine.

This is a fascinating thread. I’m writing an alternate history series with a female protagonist from the northwest coast of what we call North America. She passes through many of the evolutions mentioned here. I’m definitely following this thread. While I’m familiar with Campbell’s rules, I didn’t consciously try to follow them, but in retrospect I did. Her successes and failures drive her evolution. She is 14 at the start of the saga in 1031 CE. She is challenged almost immediately and finds the strength and intuition to take on a series of roles: messenger of danger; warleader; lover; wife (Not in the sense of modern culture); administrator, which she hated; explorer and diplomat; Spymistress (a title with implications in the Song Empire), and occasional rescuer of young people in bad situations.

This reminds me of actions that women take in Corporate America to get into the C-Suite. Until very recently, they had to become “one of the boys” and abandon their femininity. In business, compassion, feelings, connectedness, emotions, rapport talk, bringing your whole “personal” self to work were not valued traits. And then, when women get to “the top,” they realize that to stay there and maintain their emotional health, they have to rely on the very traits they’ve abandoned in order to survive the demands of “being in charge.”

There is a perfect film for the heroines journey – portrait of a lady on fire. It is a French film which cleaned up at many awards ceremonies with two central characters both women. It’s not just the writing that shows the heroines journey in this so clearly, it is in every shot. The director has Chosen not to point the camera at this character or that character – A preplanned point of view – instead she hasCarefully chosen many wide shots so that the action of the female characters can play out in almost a female heroines journey within each shot. A magnificent film.

very pleased to find this. I did my dissertation on Campbell’s racist bias against possible heroes within the black culture which were prevelent within his own working career times. Thanks for this!

Thank you for this site. I have been a fan of the Campbell’s universal monomyth but always sensed it was not capturing the felt sense of my own phenomenological inquiry. I work in ‘life excavation’ and am organizing an inquiry collective on the Heroine’s Journey- but don’t resonate with Murdoch’s model. I appreciate foundation of wholeness, but like ARK above, I’m questioning the 5 additional experiences and collapse after reaching towards leadership/ dignity/elixir in the finding “the boon”. If I may share, my Heroine’s Journey model resonates as 2 circles, one holding the other inside it as it spirals through multiple revolutions, coming and becoming at it expands. Its the invisible space- the generative process of reflective sense making – that transcends the structure of the 4 stages. The departure seeks creative expression & liberation, the initiation absorbs tools/ practices/mentors, the ordeal transmute fear into Presencing/emotional attunement, the elixir of safety is discovered, and that vessel of wisdom gets poured out to others (stage 5) and returns again to the fountain of creative liberation. This is a non binary model that acknowledges the human problem is to be solved is Love, (the diamond of dignity needs to be fully seen and heard) so that radiant autonomy can be fully witnessed and socially presenced. To me that is the Universal Child’s Journey. Thank you for allowing me a sandbox to play in!

For an example of a heroine’s journey in movies (the word “heroine” being, in my understanding, itself oxymoronic) check out the very accomplished “Her Composition”. In it, the director puts the protagonist on a traditional journey, which is however upended by force of her being a woman. The story then unfolds by taking us into new, unexpected directions told through the body of a woman, opening up new perspective of what a “heroine narrative” can be.

Great summary and conversation! Thank you.

Let us not be narrow minded. I had a student apply this journey to Achilles quite succwessfully!

As a father of two beautiful young ladies, an owner of a business that deals with feminine brands, I want to say thank you. I loved reading this.

Leave your ideas here Cancel reply

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Fellowships

Exploring the art and craft of story

Personal Essays

August 19, 2020, rewriting the “hero’s journey” to fit a feminine narrative, a writer on a hunt to understand classic story structure ponders politics, movies and her grandmother's life, and searches for a journey of their own.

Madeline Bodin

Tagged with.

Madeline Bodin as an infant with her mother, left, and grandmother in Brooklyn in 1963. Courtesy of Madeline Bodin

Harris’s journey as a Black, Asian-American woman with the ambition and credentials to run for high office is going to be different from the path traveled by white men. We don’t have to look too far back for an example: Think about the story we are still telling about Hillary Clinton. She won the popular vote, yet the narrative casts her in the role of loser.

As a journalist with a passion for narrative, I’ve given a lot of thought to story structure. But I never considered that women might need a narrative structure of their own until I attempted to find the story in my 95-year-old grandmother’s memoirs. I typed what she had written in her neat script on lined paper, and arranged her vignettes in chronological order. But something was missing: a storyline.

I was confident I could help her find that story. Ask me about story, and I’ll tell you that the “somebody wants something” is the atomic structure of story and that “first something happened, and then, because of that, something else happened” is the force that holds a story together.

But I knew that my grandmother, growing up poor and female at the beginning of the 20th century, didn’t have many choices. She wasn’t allowed many wants; her family couldn’t afford them. Still, 14 years ago, as she sat in my living room a few days after Christmas, that was the direction I was heading when I asked her, “When you were a little girl, what did you dream your adult life would be like.”

“I didn’t,” she spat, with a forcefulness that was unlike her.

I never imagined my grandmother would be a tough interview. I rephrased the question, but got the same answer. “That’s OK,” I told my grandmother. “We’ll do this another time.” I certainly needed more time to figure out how to phrase this question in a way she could answer. But there wasn’t any more time. My grandmother died a little over a month later.

So there was a certain amount of guilt that got me wondering: What about the stories of people who don’t want something? Maybe they are women with limited choices in life. Maybe their culture emphases the goals of groups like families or communities, and not individual wants and needs.

When Hillary Clinton ran for president, she was somebody who wanted something — the foundational material of a story. But that wasn’t acceptable, yet, for a woman, so her story was reframed. My grandmother had been a fan of Clinton’s when she served as a senator from New York, so it was easy for me to draw the connection between their two stories. With Kamala Harris running for vice president, is there time to learn to tell her story — women’s stories — in a fair way, before the November 3 election?

A woman’s real-life journey

The hero’s journey was once popular among Hollywood screenwriters. It was certainly at play in the success of “Star Wars.” Writer and director George Lucas has said in interviews that he relied on “The Hero with a Thousand Faces” while writing his screenplays. Luke Skywalker’s journey belonged to the archetypal hero and spun box office gold.

So last year, when I learned there was a book called “The Heroine’s Journey,” (and I thought we might have a second female presidential candidate) I was in. Maybe this book had the answer about women’s stories that I was seeking.

In response, Murdock put together her own heroine’s journey. This journey starts when a woman separates from “the feminine” and retraces the hero’s journey. But that’s only the beginning. Once a heroine finds the “boon of success” that ends the hero’s journey, she experiences a spiritual death. Traveling a man’s path is not fulfilling for her. So, Murdock’s heroine works to reconnect to the feminine.

As I read, the second half of the circle — the part about fighting, then healing, the patriarchy — felt to me like an unnatural growth, a pimple. I resisted the notion that women should have to fight the patriarchy. I’m looking for a fundamental story structure for women, and I’d like to find one that works in all societies, not just patriarchies.

In a later chapter, Murdock describes how she developed this journey to help her therapy clients, many of whom were women who were outwardly successful but deeply unhappy. Believe it or not, I did not realize until that moment that I was reading a self-help book, not a literary or anthropological work, as Campbell’s book is. “The Heroine’s Journey” wasn’t giving me a universal story structure, so I kept reading.

I found a 2011 article in Los Angeles Magazine by , who would later become the writer and producer of the television series “Transparent.” The article is titled “Paging Joseph Campbell: turns out that the fabled Hero’s Journey is a bunch of hooey when you’re writing about heroines.”

Soloway had mastered the hero’s journey as a screenwriting form, and rejected it for heroines’ stories. They looked to movies written by women about women, such as Diablo Cody’s “Juno” and Callie Khouri’s “Thelma & Louise,” for patterns. Soloway decided that the structure of a heroine’s story is circular, but has different stops and winds forward differently than those along the hero’s journey. Soloway sees it more like a Slinky or a road that winds up a mountain, where a traveler views the same landmarks from a higher elevation with each turn around the circle.

Soloway writes about Murdock’s book and sees their two versions of the heroine’s journey as similar.

The three ages of the woman’s journey

In the chapter titled “Pure Heroines” in her 2019 book of essays, “Trick Mirror,” Jia Tolentino classifies literary heroines into three ages. The heroines we first meet as children are independent and active, she says; she uses Laura Ingalls from the Little House on the Prairie series as a frequent example. The heroines we meet as adolescents are traumatized; think of Katniss Everdeen in “The Hunger Games,” forced to kill to save her own life. And the heroines we meet as adults — Tolentino draws heavily on “Madame Bovary” and “Anna Karenina” — are bitter.

Within these age classes, it seems that the child heroines likely follow the hero’s journey. Tolentino paraphrases Simone de Beauvoir’s “Second Sex:” a girl is simply a human being before specifically becoming a woman. A girl’s journey is not much different from a boy’s or a man’s. Then something happens to change the map of her journey.

“Adulthood is always looming,” Tolentino writes. Specifically, she writes, marriage and children mean the end of the freedom to adventure. I would expand that to include sexual desire as an end. That may mean being the object of men’s desire, welcome or not, or it might mean wanting to be desired. So for our adventurous girl, maturity means a shift from fulfilling her own goals to helping others (husband, lover, children) meet their goals, or losing their place as a protagonist by becoming an object in someone else’s story. (Woman as bus station, again.)

The life cycle of the literary heroine that Tolentino describes could be a journey of its own: the freedom of childhood, a trauma, and an adulthood of disconnection, anger or bitterness.

If you don’t like the way that journey ends, well, neither do I. I think it’s important to remember that Madame Bovary and Anna Karenina lives were scripted by men. And that while Campbell was categorizing epic tales about heroes, he included both tragedies and comedies among the stories he included in his analysis. I don’t want to give up on a happier ending for women’s stories until a few comedies are in the analytical mix.

But Tolentino’s essay focuses on characters within stories, not on the structure of those stories. I’ve plucked out the ideas that fit here. In a February article in The New York Times Magazine, Brit Marling, an actor, writer and producer whose show, “The OA,” ran for two seasons on Netflix, addressed women’s stories directly. Marling says that she had to write her way out of the confining roles she was playing, both on the screen and in her life. But it wasn’t easy. “Even when I found myself writing stories about women rebelling against the patriarchy, it still felt like what I largely ended up describing was the confines of patriarchy.”

Her success as a filmmaker gave her access to a new role in others’ films: the strong female lead. You know this character: “She’s an assassin, a spy, a soldier, a superhero, a C.E.O.” Marling writes that playing these characters made her feel formidable and respected. Eventually, however, she realized that, far from portraying some deep truth about women, she was depicting masculine traits in a woman’s body. Do movies and television shows always have to kill the feminine?

At the very end of the article, Marling compares the hero’s journey to a male orgasm, but says she has only questions, not answers, about how a woman’s journey would unfold when it doesn’t merely reflect a man’s desire.

Writing to a new ending

At the end of my own journey in search of a universal structure for women’s stories I found myself, like Marling, with no clear answers, but a better idea of where to search for them. I’ll keep looking for answers in the stories that women tell about other women for other women. And I’ll look to writers like Marling who have given these ideas a lot of thought.

I’ve also realized that, yes, fighting patriarchal notions, cultural restraints, male violence, and male abuse shouldn’t be part of the fundamental story shared by womankind. But I think that we’re stuck with it for a while. Even Sweden, where women enjoy legal rights and cultural equality that I’m not sure we in the United States can really grasp, has made crime novels featuring violence against women one of its leading exports.

We’ve already seen how the story of Kamala Harris, possibly the next vice president of the U.S. and a future contender for the presidency, is getting bent to fit the mold; I can only imagine what the next three months will bring.

If “somebody wants something” is the atomic structure of story (and I do realize that’s a rule of my own creation), and we live in a culture where a woman’s desire — sexual, political, financial — is considered unseemly, we have a fundamental problem telling any woman’s story. In this environment, women have a hard time identifying their own desires and seeing the story in their own lives.

I suspect that at least part of the answer lies in not being too respectful of Campbell’s vision when we chose to use the hero’s journey as a story structure.

Douglas Burton, a novelist and blogger , wrote a series of blog posts about women’s stories, inspired by “Game of Thrones,” “Wonder Woman,” and his own novel about the Byzantine Empress Theodora, all written by men. Despite the male focus, he noticed that for the hero, home is a safe space, where for the heroine, home is often a place that must be fled. For the hero, the enemy that must be overcome is the outsider: a monster, an invader, or even death itself. For the heroine, the enemy that must be confronted may be someone near to her, someone beloved to her, or even herself.

I think Burton has a good point. Maybe the heroine does not return with a boon for all humanity. We can tell the story anyway. Maybe the heroine is not called to adventure, but is spit out into the world by her home circumstances. Maybe the monster the heroine must slay is not alien to her, but the patriarchal elements of her own culture.

Madeline Bodin with her mother (center), grandmother and infant daughter. Vermont 1996. Courtesy of Madeline Bodin

A wise journalist, editor and teacher once said, that when you are stuck, you need to ask more questions. So I called my mom to ask her what she thought had made my grandmother so angry when I asked about her life story. My mother thinks my grandmother was bitter at the end of her life, and that made it hard for her to think about her life’s happier beginning. (And my mother hasn’t even read Jia Tolentino’s essay.)

I was glad to hear that my mother thought that my grandmother once had desires and had made choices to fulfill those desires. I was glad to know that she had a story once, even if I won’t know the truths behind that story. Maybe I was wrong about the role of thwarted choices and unacceptable desires in women’s fundamental narratives, I said to my mom.

That’s when my mother launched into a story of her own. How when she was in high school (in the middle of the 20th Century), women had few choices. How her father thought college was a waste of time for a woman. How she was determined to go anyway, so she worked two jobs to pay for it.

And then she apologized. “I know I’ve told you this story many times before.”

Madeline Bodin is a freelance environmental and science journalist who is based in Vermont, but will travel just about anywhere for a good story.

Further Reading

When the bounds of conventional journalism are too tight, by brendan meyer, how protest songs echo — and sometimes lead — the stories of our times, by dale keiger, a displaced writer picks up a camera — and falls back in love with learning, by roy wenzl.

Author, educator, and photographer

- Meet Maureen

- Selected Work

- Changing Woman Gallery

- Speaking/Contact

Articles: The Heroine’s Journey

By Maureen Murdock Published in the Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion edited by David A. Leeming, 2016

In 1949 Joseph Campbell presented a model of the mythological journey of the hero in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, which has since been used as a template for the psycho-spiritual development of the individual. This model, rich in myths about the travails and rewards of male heroes like Gilgamesh, Odysseus, and Percival, begins with a Call to Adventure. The hero crosses the threshold into unknown realms, meets supernatural guides who assist him in his journey, and confronts adversaries or threshold guardians who try to block his progress. The hero experiences an initiation in the belly of the whale, goes through a series of trials that test his skills, and resolves before finding the boon he seeks – variously symbolized by the Grail, the Rune of Wisdom, or the Golden Fleece. He meets a mysterious partner in the form of a goddess or gods, enters into a sacred marriage, and returns across the final threshold to bring back the treasure he has found (Campbell 1949, pp. 36–37).